CONTENTS

Section 1 - Implications: A First Circle of Connections

Section 2 - A Second Circle of Connections: Contexts

Section 3 - A Third Circle of Connections: The Logos in the Cosmos

Section 4 - A Fourth Circle of Connections: From Within Creation

Section 5 - A Fifth Circle of Connections: Human Being

Section 6 - A Sixth Circle of Connections: The Trinity

Section 7 - A Seventh Circle of Connections: The Eucharistic Universe

Section 8 - Dimensions: Death

Section 9 - Dimensions: Love and Sex

Section 10 - Conclusion

Bibliography

AN EXPANDING THEOLOGY

Faith in a World of Connections

Anthony J. Kelly CSsR

Section 6

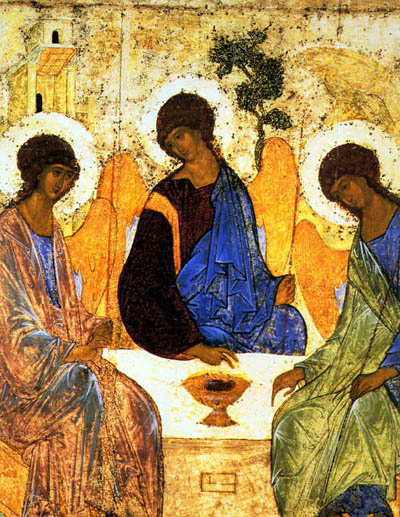

A Sixth Circle of Connections: THE TRINITY

God is ‘light', ‘love' and ‘life' (Cf. 1 John 1:4; 4:8; 5:20)), as the communion of the three divine persons, Father, Son and Spirit. Any effort to relate Christian faith to a contemporary worldview would be very limited if it left out the central doctrine of the Trinity. In the vision of faith, creation is being drawn into the divine love-life, as God acts in the incarnation of the Word and through the outpouring of the Spirit. As the Trinity gathers creation into itself, the universe comes home; and all the struggling emergence of time finds its absolute future.

Before trying to tease out some of the more relevant aspects of trinitarian faith, one must register a regret that doctrinal controversies have often reduced this most comprehensive of Christian mysteries practically to the point of absurdity – at least in the minds of most Christians. What should have been a celebration of God as the absolute Being-in-Love at the heart of the universe, what might have been a sense of the divine community enfolding all conscious creation into its own love-life, appeared as an exercise in supercelestial mathematics in which one could not be properly multiplied, or divided, by three.

In recent years, no doubt out of a presentiment of new relevance, trinitarian theology has been undergoing a considerable renewal.[1] Here I shall attempt no overall statement, but merely emphasise some of the perspectives I find increasingly relevant to current ecological and cosmological discussion.

1. Ultimate Reality as Relational

First of all, what kind of reality is Christian faith trying to objectify out of its experience of God? How does such experience and meaning affect all our experience of reality?

Most radically, the analogical, all-connecting imagination of the Christian faith is envisaging the ultimate ground of our existence as intrinsically relational. Doctrinal theology speaks of the divine persons as ‘subsisting relationships'. The divine three can only be understood in relation to one another, as ‘for' and ‘in' the other. The absolute one-ness of God is concretely realised in a limitlessly self-communicating relationality. God is God by being a communion of mutual self-giving. The Be-ing of God is a life of communion. And the life of God is one of unrestricted, all-embracing love.

The originating Love that God is (Father) expresses its fullness in the Word, and rejoices in its infinite excess in the Spirit. In that self-utterance and self-gift, all God is, all that the universe is or will be, is contained. The universe, emerging in the long ages of time, is ever being called and held in existence by the gift of God. The eternal Now of Trinity is the matrix of time, not its contradiction.[2] That relational vitality, which theology calls the ‘divine processions' of the Word and the Spirit, is creating the universe in its dynamic image. What is procession ‘within' the divine mystery, is imaged in the created process of the universe.[3] The universe finds its ultimate coherence in as much as the Trinity draws it to participate in its own field of relationships, to be alight in the Word, enlivened in the Spirit, and surrendering in thankfulness to the originating love of the Father. From its experience of this relational field of divine presence, Christian faith comes to confess the Trinity as the transcendent presence immanent in all existence. All instances of being, becoming and life have their beginning, form and goal in the ‘Love-Life' of God, ‘so that God might be all in all' (1 Cor 15:28). The evocative language of Nicholas of Cusa returns such intense theological expressions to the world of mystical imagination: ‘The Godhead is the enfolding and unfolding of everything that is. The Godhead is in all things in such a way that all things are in God'.[4]

The Word was in the beginning as the primordial self-expression of Love. God is self-differentiated in this Other, and Love becomes self-communication. The universe has been uttered into existence to be a world of endlessly differentiated ‘words', logoi, meanings. For, as Aquinas reminded us, ‘created things cannot attain to the perfect image of God in a single form'. It was fitting ‘that there be a multiplicity and variety in created things so that God's image be found in them perfectly in accord with their mode of being'.[5]

But there is the third divine person. Father and Son become Trinity through the Spirit. The Love that has differentiated itself, and been self-expressed in the Other, becomes, in the eternal now, a communal activity ‘in the unity of the Holy Spirit'. We may understand the relational dynamics of creation, then, as a participation in the ecstasy of the Spirit, For the Breath of God's moves the differentiated, distinct, and independent realities of creation into self-transcending communion. In this perspective, the cosmos lives and breathes the mystery of the ‘primordial, expressive and unitive' Being-in-Love at the heart of its existence.[6] If the original and ultimate reality is inherently relational, if ultimate unity is self-giving communion, trinitarian faith is a healthy disturbance for all closed little worlds of isolated independence. Defensive alienation from the other, resistance to peace and reconciliation, any hardened disharmony with the rest of creation sets us outside the stream of life.

In an obvious sense the ecological imagination is more hospitable to a trinitarian conception of ultimate reality than the former dominant mechanistic worldview. A mechanistically-modelled science had little patience with any theology, let alone any theology needlessly complicated with trinitarian references to processions, relationships, the unity of the divine nature and the plurality of the divine persons. But current views of the processive and relational character of cosmos might be expected to find some of the tradition of trinitarian theology quite intriguing. The contemporary paradigms of science and the theological paradigm of God seem to be converging. For two thousand years, theology has regarded the ultimate as a realm of processive, interpersonal, relational life, for God is concretely on only in a manifold of relationships. As a more holistic science realises this tradition of theological thought and faith, points of dialogue can emerge, in the one exploration of the real.[7]

2. Productive Models from the Past

Traditional trinitarian theology, following Aquinas, passes from the consideration of the processions and relationships of the divine persons ad intra (i.e., in the eternal ‘within' of God) to their presence and relationships ad extra, in the universe of creation. The self-communication of the Trinity ad extra is treated under the heading of the biblical category of ‘mission' or ‘sending' – the way, for instance, God ‘sends' the Son and Spirit into the world. While current theological efforts tend to find such categories too abstract and spatial[8], I am beginning to suspect that there is something to be gained, given the present evolutionary horizon, in attempting to retrieve some aspects of the Thomist approach.[9] In giving a brief indication of this point, I will be taking some liberty with the traditional terminology, but only in the hope of suggesting a better comprehension of its meaning in the present context.

The following points might be made. For example, Aquinas asks, how can a divine person be ‘sent'? The problem here is to imply neither inequality in the co-equal Trinity, nor some primitive form of spatial movement – as though God were not everywhere in the first place. In his answer to this question, Aquinas makes these two points:

· The divine person is sent inasmuch as the eternal procession of the Son/Spirit is prolonged into time and history. The life, the consciousness of God thus takes in the world of time and its emerging world.

· Because the mission is an extension into time of the eternal procession, it means that the divine persons begin to exist in the world in a new way: ‘Thus, the Son is said to have been sent by the Father into the world, even though he was already in the world, because he began to be in the world in a visible way by taking flesh'.[10]

We can understand the divine missions as the self-immersion of the Trinity in the created universe. The risk, fragility and movement of a temporal world enter into the one Trinitarian consciousness. The world is an aspect of God's own experience. From this point of view, the missions of Word and Spirit are the Trinity's dynamic openness to the world and to history. The Mystery communicates itself to the created other in order to enfold creation into its communal life.

But there is a second point. Aquinas allows for two dimensions of these missions, the ‘invisible' and the ‘visible'. The failure to transpose this traditional distinction in an adequate manner has locked Christianity into a narrowness that is ill-prepared for the cosmic scope of its present challenge.

So, first, a word on the invisible missions. We begin with the recognition that God is present to everything and everyone in an absolutely fundamental manner, as the sheer Be-ing, Ipsum Esse, the source of all being. As the giver of existence, God is present in the innermost depths of all reality – as described in a chapter 4. Yet from the depths of the ocean of Beiing in which we exist, there comes a wave of freedom, of self-communicating love. God is not content, as it were, simply to be the nameless universal mystery at the heart of reality. Beyond giving ourselves to ourselves, The Trinity wishes to give itself to us, so that we can enter a new realm of a new selfhood and communion. This is the area of grace. By receiving this new gift we are not only God's creatures but become God's intimates. The Trinity acts in creation with the fullness of self-communication, to be present to creation in the nakedness and special connectedness of love.

The divine gift brings about that transformation of human consciousness which tradition names as ‘sanctifying grace'. There occurs a special experiential immediacy with the divine.[11] The human self is ‘conformed to God'. Through love it is made like the Spirit of love, and through new understanding it shares in the wisdom of the Word: ‘because by such knowing and loving, created consciousness (rationalis creatura) makes contact with God in its activity; in this special manner God is said not only to be in such a consciousness, but to dwell in it as in his temple' (STh I, q. 43, a. 3). Thomas also speaks of the Father as given and indwelling through grace, but not as ‘sent'. The first divine person is present precisely as the source of all divine life and giving, the Father who is ‘above all and through all and in all' (Eph 4:6).

A horizon of loving presence precedes any particular context of time or space. In this way, the Word and Spirit are ‘invisibly' sent to indwells human consciousness. However unnamed, unexpressed, in its unknown depths human consciousness is awakened into a new level of being. It begins to participate in the very consciousness of God as self-communicating love. Our capacities for dialogue are now extended to loving communication with the divine: ‘for the Word is not any kind of word, but the Word breathing love.'[12] Wherever there is evidence of a consciousness lovingly alive, in reconciling wisdom and self-transcending love, it is the dwelling of God.

It is true that this metaphor of ‘sending' or mission might too easily give the impression of the divine persons arriving in the world from the outer space of the divine realm. On the other hand, once the spatial limits of the metaphor are recognised, the reality is more like a blooming or an emergence of the mystery out of the depths of existence. What could have been, or appeared to be, a universe of simple fact, however uncanny, is now irradiated as a field of divine consciousness. God dwells in us and we dwell in God in the circulation of divine life and love.

But there is more. The divine missions are not only ‘invisible' as the Word and Spirit illuminate and enkindle the indefinable horizon of life. They are also visible. The divine Word who had been invisibly present in grace, becomes incarnate. The Spirit, too, who had invisibly dwelt in the hearts of all good people, is manifested as a movement in history, in transformed lives, in communities of faith, in all the signs and sacraments of Church. The reality of God's self-giving is attuned to the embodied reality of being human. It takes shape in the time and space of this particular world. The divine mystery does not inhabit a transcendent celestial realm apart from the flesh-and-blood of our world. Nor, says Aquinas, do we:

Now it is connatural for a human being to be guided by the visible to the invisible. Through the evidence of creatures, God has in some way manifested himself and the eternal processions of the persons. Likewise, it is right that the invisible missions of the divine persons be made manifest through visible creation. Now this occurs in one way with the Son, and in another way with the Holy Spirit: ... the Son is visibly sent as the author of holiness; but the Spirit as the witness to that holiness.[13]

The embodied world of our existence is the natural milieu for human communication. As it respects this given ‘ecology' of human existence, trinitarian love manifests itself to communicate divine life and communion. The created world, in all its differentiation, structures, relationships, and dynamics already evidences its primal emergence from the Be-ing and relational reality of God (the processions). A trinitarian dynamism is originally inscribed into every element of the created world. In a further gift, the trinitarian orientation is intensified within this world of experience. The visible mission of the Word incarnate in Jesus Christ, enacts and expresses, in the world of human communication, the meaning of the mystery at work. And the Spirit, symbolised in the water, the wind, the air, the flame of our natural experience, is expressed as the field of ultimate connections.

In this perspective, the Church is an extension of the visible missions, as that part or moment of the world that is expressly alive to the universal mystery of relational love at work. The community of Christian faith deals in words and signs and symbols and sacraments of the trinitarian mystery. It is part of the ecology of God's presence, even if not the totality of it.

Further, the ‘connatural' world of human communication that Thomas recognised as the place of God's express self-manifestation, is now emerging as a time-structured evolutionary process. The primordial dynamism of the processions, their extension into creation through the invisible and visible missions, now demand, if God's communication is to be revealed in its full connaturality, a re-expression in an evolutionary perspective.

In this perspective, the invisible missions are ‘invisible' precisely because they energise the indefinable totality of the universe. Animated by such energies, the emergent universe can be contemplated in the light of one vast act of divine self-communication. The self-giving God becomes the soul, the heart, the mind of the world's emergence: ‘There is... one God and Father of all, who is above all and through all and in all' (Eph 4:6). On the other hand, the ‘visibility' of the missions discloses the universe in terms of God's embodiment. The mystery of Love incarnates the Word in the whole cosmic body of creation as the form and structure of creation. It en-worlds itself as Spirit acting in all the self-transcending dynamics that characterise our cosmic becoming. And, as the Father is intimated as the source of both Word and Spirit, the world moves forward within an horizon of the absolute future for the whole of temporal existence.

In this way, the trinitarian God is ‘enworlded'. The divine communal life is the relational ground of a cosmos of growing connections and relationships. If the Word is incarnate as universal meaning, if it is first a question (John 2:38), its full expression is in a desire welling up from the depths of the incarnation: ‘As you, Father are in me, and I in you, may they also be in us... may they be one as we are one' (John 17:21-23). And in a promise: ‘When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all truth... and he will declare to you the things that are to come' (John 16:13).

Realism, of course, demands an acknowledgement of the tragic world of conflicts in which we live. Whatever the eschatological hope, this is no whole world of harmonious connections. For that reason, we must bear in mind that visibility of Love in such a world must first of all be healing and reconciling, before it is simply transforming. Divine self-giving is marked with the intensity of self-sacrifice. The God-self communicated in the Son and the Spirit is directed to human beings locked in an apparently insuperable problem of evil. Incarnation goes to the point of crucifixion. And the Father is revealed as having no self-disclosure in this world other than through the Crucified One. Similarly the Spirit is exposed to the world of self-enclosure, of non-relationality, by witnessing to no power and no truth other than that of the selfless love of the Cross. God's visibility in the world, then, connects with our problem of evil. It is love revealed as exposed to, but ever-greater than, the alienation, failure and fragmentation of our world. If it promises transformation, it is first of all a healing for the self-destructiveness of our ways.[14]

In this way, the traditional schema of processions, divine relations, invisible and visible missions can be reworked so as to engage the new world of our relational experience..

3. An Extended Frame of Reference

There is nothing new in exploring the reality of God by way of analogy with created realities, nor in interpreting the world of created reality in the light of God. Augustine's ‘vestige' and ‘image' doctrine, with its underpinning in Greek exemplarism, is a good instance.[15] In Catholic tradition, it developed into the typically Franciscan cosmic sense of all reality sacramentally manifesting God. For example, over seven hundred years ago, Robert Grosseteste, the first Chancellor of the University of Oxford, could contemplate a speck of dust to find in its existence, form and goodness a manifestation of the three divine persons.[16] Now, a speck of dust caught in the light beaming in through a medieval scholar's window is rather different from other specks we know today. For example, the earth is a mere speck in a universe of some hundred billion galaxies. Indeed, the Big Bang represents the unfolding of the cosmos through billions of years from the infinitesimal super-compressed speck of its beginnings. Theology is, therefore, in continuity with its past, contemplating the originality, the dynamic form, the wonder and beauty of cosmic reality. In so doing, a reflective faith is coming to a fuller insight into the deeper implications of its central mystery.[17]

Likewise, St Bonaventure, in his ladder of contemplation, could consider creation as implying a trinitarian presence on three ascending rungs of intensity. First, there are the footprints or ‘vestiges' (vestigia) of the Creator found in the pre-personal. Secondly, there is the divine ‘image' in the spiritual creature with its powers of intelligence and love. Thirdly, the divine ‘likeness' brought about as the created spirit is transformed through grace:

the creation of the world as a book in which the creative Trinity shines forth. It is read according to the three levels of expression, the ways of vestige, image and likeness. By these, as up a ladder's steps, the human intellect has the power to climb by stages to the supreme principle which is God.[18]

The implied metaphor of a stable ladder leading upward tends now to be replaced by the arrow of time moving forward in an evolutionary direction. The ‘footsteps' of God now have to be tracked in the history of the fifteen billion years of the world's emergence. The image of God is now disclosed in terms of human consciousness emerging in such an evolutionary world as a light and a love in which the universe is known and appreciated. The likeness of God, in its turn, is disclosed in the transformation of that consciousness as it indwells and is inhabited by the primordial mystery of creative Love.

For his part, Aquinas sums up the themes of the great Greek theologians, especially Athanasius and Gregory of Nyssa, when he treats of the presence of the Trinity in the act of creation:

[T]he divine persons are causes of the creation of things in the order of their procession, since God acts from his knowledge and will as a craftsman acts in regard to what he produces. The craftsman acts through a word conceived in his mind and through love in his will in reference to what is to be made. Hence the Father creates through his Word which is the Son, and through his love which is the Spirit.[19]

In such a vision, the trinitarian mystery is involved in the very mystery of what it means to be a creature. The trinitarian processions of Word and Spirit are at the foundations of the cosmic process. Indeed, Aquinas goes on to say that

The knowledge of the divine persons is necessary for us for two reasons: in the first place, to have a right sense of the creation of things. Because we say that God created all things by his Word, the error is excluded of holding that God produced things out of the necessity of his nature. Because we hold that there is a procession of love within him, it is clear that God did not produce creatures out of some extrinsic need, but on account of love for his goodness... In the second place, and this is more important, [the Trinity is disclosed] that we might have a proper sense of the salvation of the human race, which is brought about by the incarnation of the Son and through the gift of the Holy Spirit.[20]

That ‘right sense of creation' implies that creation is not a divine necessity. It is an act of love, a communication from the heart of God. Secondly, the ‘salvation of the human race' is based on the self-communication of God to the cosmic, evolutionary process, just as it is energised into a final unity ‘through the gift of Spirit', the Holy Breath and atmosphere of life to the full.

In creative continuity with such traditional resources, trinitarian theology is free to exploit all the resources of language to explicate the trinitarian form of creation. Because it cannot rest content with an undifferentiated sense of the presence of the mystery, it explores the variety of ways in which its presence can be discerned in the relational and processive meaning. In this regard, Trinitarian theology traditionally employed an evocative technique known as ‘appropriation'. General considerations of the divine attributes are given a trinitarian focus. Typical examples, in reference to the Father, Son and Spirit respectively, are power, wisdom and goodness; unity, equality and harmony; eternity, beauty and form; omnipotence, omniscience and will; efficient, exemplary and final causality, and so on. With such a plethora of terms, trinitarian thought tried to give some expression of the encompassing mystery of God ‘ever beyond us', as Father, all-inclusive Source and Goal; of God now ‘with us', as Word and Son incarnate; of God ever ‘within and between us', as Holy Spirit, works through all creation.

These past expressions anticipate a new set of trinitarian connections drawn from the book of creation as read through modern eyes. Many writers speak of the direction of evolution in terms of increasing ‘differentiation, subjectivity and communion'.[21] The initial cosmic event unfolds into a marvellous variety of particles, forces, elements, life-forms, cultures. With that differentiation, there occurs an increase of interiority and consciousness. Living, self-organising unities emerge into growing complexity, through the nervous system to the human brain. In the human phenomenon, consciousness emerges as intelligence and freedom. Evolution becomes conscious of itself. The universe is self-aware. And in that self-awareness, the mystery of our common origins and shared destiny comes to dwell: communion.

Trinitarian theology could make many connections with these three principles. For example,

- the mystery of the self-differentiation of God through Word and Spirit could be understood to be the primordial implication of the principle of cosmic differentiation. The manifold of creation emerges out of God's original self-utterance and joy in being.

- Likewise, the development of interiority is climaxed in being drawn into the divine realm of consciousness. In faith, hope and love, human consciousness participates in the trinitarian vitality of self-presence. We begin to know and love ourselves and the universe of divine creation as God does. Interiority thus culminates in dwelling in the divine mystery, and its indwelling of our minds and hearts.

- Finally, creation is not only grounded in the self-differentiation of God; not only does it participate in the interiority of the divine self-knowledge and love, but it expands in the field of divine communion. The self-giving relationality of God's Being-in-Love affects all created differentiation and subjectivity with its own unity-in-difference. To be, to live, to develop has the trinitarian meaning of consciously being, living and developing from, and for, and with the other. Trinitarian communion is, thus, the limitless field in which interpersonal, ecological and cosmic communion can be realised. In short, our planetary existence is a living image of the Trinity, and a progressive participation in the communal life of the divine mystery.[22]

Beatrice Bruteau provides a remark that brings many of these points together. She is in a long tradition when she says,

The cosmos has all the marks of the Trinity: it is a unity; it is internally differentiated but interpenetrating; and it is dynamic, giving, expansive, radiant. And, as a work of art, the cosmos has another important character: it does not exist for the sake of something else, something beyond itself; it is not useful, it is not instrumental; it is an end in itself, self-justifying, valuable in its own right and in its very process. This, I think, is foundational for... ecological virtue...[23]

4. Conclusion

A vivid sense of the trinitarian dimension of human existence profoundly affects the lived sense of human selfhood. Christian theology speaks of the divine indwelling. It is at once God dwelling in us, and ourselves dwelling in God. To search into who we are is find ourselves in the presence of God, the Self in all our selves. The three classic biblical expressions of such intimacy with the divine mystery are familiar: We are

· temples of the Holy Spirit, the divine creativity hidden in all creation;

· members of the Body of Christ in whom all things cohere;

· we share in the divine life as sons and daughters of the Father as the final all-welcoming mystery of the future.

Such an indwelling means that God is known with an ‘inside' knowledge. It is familiarity with the reality of God born out of participation in the Love-Life that God is: ‘Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God... For God is love... No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is perfected in us' (1 John 4:7-12). To experience God in such a way is to find oneself as a ‘connected self', a self-to-be-realised in relationship to the other. This ‘other' today admits of a global, ecological, and cosmic extension. Hence the adoration of such a God orientates the believer into a world of relationship and communion. It implies an agenda for the transformation of ourselves, our communities, our global co-existence.

If, in this brief reflection, we have moved trinitarian faith from the background to the foreground of our thinking, it is not for the sake of needless complexity. But in a world of both needless complexity as well as astonishing connectedness, Christian faith can find a new health and a new wholeness in contemplating the universe in the light of its fundamental mystery.

[1]. For a considerable bibliography and a fuller expression of my own approach, see Kelly, Trinity of Love.

[2]. For a rigorous examination of the theme of divine eternity, see John C. Yates, The Timelessness of God (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1990).

[3]. I do not think this distinction is sufficiently appreciated. When it is not, ‘process' becomes the ultimate reality, not ‘procession'. There is a big difference between deifying the process and adoring the ‘proceeding' divine persons. Even a survey of such towering expertise as Barbour, Religion in an Age of Science does not mention the relevance of the trinitarian mystery to current evolutionary and genetic understandings of reality. Remaining only with the category of process strikes me as being theologically far too timid.

[4]. Quoted in Sheldrake, The Rebirth of Nature , 198. Noteworthy, too, is the influence of Sheldrake on the deep trinitarian structure of Bede Griffith, A New Vision of Reality.

[5]. ScG, l. 2, c. 45.

[6]. Here I have adapted three terms taken from John Macquarrie, Principles of Christian Theology (London: SCM Press, London, 1977) 195-202.

[7]. For example, see the various references to the Trinity in Capra, Steindl-Rast and Matus, Belonging to the Universe, 61-63; 106-109; 118; 131-33.

[8]. Including my own, as in Trinity of Love. See 133-172 for evidence of a different method.

[9] For an overview of Aquinas' approach to theology, see Anthony J Kelly, ‘A Multidimensional Disclosure: Aquinas' Theological Intentionality', The Thomist 67/3 (July 2003) 335-374.

[10]. STh I, q. 43, a. 1.

[11]. STh I, q. 43, a. 5, ad 2.

[12]. STh I, q. 43, a. 5, ad 2.

[13]. STh I, q. 43, a. 1. For further treatment of the missions, see Jean-Hervé Nicolas, OP, Synthèse dogmatique: de la Trinité à la Trinité (Paris: Beauchesne, 1985) 231-265.

[14]. See Kelly, Trinity of Love, 168f; 195-202.

[15]. De Trinitate VI; VIII-XV.

[16]. Servus Gieben, ‘Traces of God in Nature according to Robert Grosseteste', Franciscan Studies XXIV (1964) 154-6.

[17]. For the profound analogical shift in our understanding of God's relationship to the world, a most useful article is Carol Jean Vale, SSJ, `Teilhard de Chardin: Ontogenesis vs. Ontology', Theological Studies 53/2, June 1992, pp. 313-337. The author implies that a more critical comprehension of the Thomistic tradition of analogy would make for a greater continuity between Aquinas and Teilhard.

[18]. Intinerarium Mentis in Deum c. 3, n. 5.

[19]. STh I, q. 45, a. 6, ad 2.

[20]. STh I, q. 32, a. 1, ad 3.

[21]. For example, Thomas Berry, The Dream of the Earth (San Francisco: Sierra Book Club, 1988) 44-46.

[22]. See Kelly, Trinity of Love , 8-13. For related biological applications, see Sheldrake, The Rebirth of Nature, 193-199. Also, Fritjof Capra, reflecting on the `self-organising' properties of matter manifested in ‘the pattern of organisation, the structure, and the process', remarks, ‘The funny thing about the concept of self-organisation is that it can be presented as having a “Trinitarian” nature' (Belonging to the Universe, 117). Bonaventure and Thomas Aquinas would not have found it so odd.

[23]. Beatrice Bruteau, ‘Eucharistic Ecology and Ecological Spirituality', Cross Currents Winter 1990, 504.