CONTENTS

Section 1 - Implications: A First Circle of Connections

Section 2 - A Second Circle of Connections: Contexts

Section 3 - A Third Circle of Connections: The Logos in the Cosmos

Section 4 - A Fourth Circle of Connections: From Within Creation

Section 5 - A Fifth Circle of Connections: Human Being

Section 6 - A Sixth Circle of Connections: The Trinity

Section 7 - A Seventh Circle of Connections: The Eucharistic Universe

Section 8 - Dimensions: Death

Section 9 - Dimensions: Love and Sex

Section 10 - Conclusion

Bibliography

AN EXPANDING THEOLOGY

Faith in a World of Connections

Anthony J. Kelly CSsR

Section 5

A Fifth Circle of Connections: HUMAN BEING

In turning now to a more explicit consideration of human existence, I begin by stating the obvious: of all the creatures in the universe, of all the variety of life-forms, the human is a question to itself. And there is no hiding from it. If the stream of life carries us on, its occasional pools of reflection are places where the deepest questions surface. Where do we come from? Where are we going? To whom are we responsible? What should we be doing? [1]

1. The Human Question

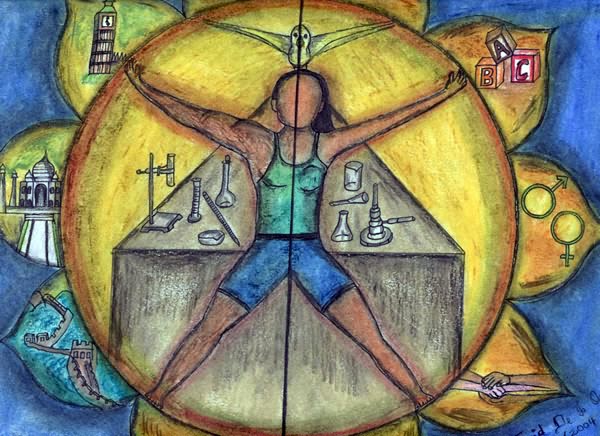

The need to question arises out of an inevitable collision of limitation and possibility. In one way, there is an obvious living unity about our existence: before any distinction or analysis, we simply are : ‘life is fired at us point-blank'' (Ortega y Gasset). Yet, as we turn to consider all the dynamics and structures implied in what and who we are, no simple description seems possible. Nature and person, body and soul, man and woman, individual and community, society and culture, cosmos and history, God and the universe – these are just some of the dualities employed in our unfinished self-descriptions. We human beings seem to be destined to make life complicated. The great saint of East and West, Maximus the Confessor, speaks of the human being as ‘the laboratory in which everything is concentrated and itself naturally mediates between the extremities of each division, having been drawn into everything in a good and fitting way through its development'.[2]

It is this very complication that fuels the search for some comprehensive meaning in which to focus the whole thrust of our conscious life. The heart longs for something into which to pour its deepest passion to connect and belong. But how is such a meaning and such value to be expressed? With difficulty. The various levels of our consciousness, the fragmentary character of our perceptions, the diversity of our viewpoints, often enough leave us stranded in complexity. On the other hand, we do have ourselves. Better, we are selves, conscious in this moment, aware of a universe, yet earthed in this tiny planet in a galaxy in which one hundred billion suns are said to shine. The more comprehensively and critically we can claim the structure and dynamics of that human self in its unfolding relationality, and in its rootedness in the cosmos itself, the more telling any formulation is likely to be. The great Goethe evokes the uniqueness of human existence in his aphorism, ‘Man is the first conversation that nature holds with God'.[3]

The summit of such converse has already been touched on in our reflections on the meaning of the Incarnation. In Christ, the world's path to God and God's way into the world are embodied: ‘the Word became flesh and lived amongst us, and we have seen his glory' (John 1:14). Though the Incarnate Word has a universal reference, there is also a sense of divine tact. The Word is uttered into the human history, but not so as to stop the human conversation: ‘... what we will be has not yet been revealed ‘ (1 John 3:2). The flow of life goes on, and history passes into new ages – as in the present when a globalisation of human experience is occurring. The Word indeed was made flesh and dwelt amongst us; but that ‘flesh' is a world of questions. What does it mean to hearken to this Word when we come to understand that the human is one of a million other species? How is the universe of current science hospitable to the grandeur and smallness of human existence? And between those two questions stands the explicitly theological one: How can Christian faith today be a conversation within the ecological and cosmically-attuned culture of our day? In short, it is a good time for Christian believers to remember that the first words of the Word in John's Gospel is a question: ‘What do you seek?' (John 1:38).

2. Language and Culture

If the consideration of human existence plunges us into a world of questions, far more obviously does it put us in a world of words. We need to speak what we are, to word our experience, if we are ever to appreciate it critically. Now, the languages available to our search for human meaning often foreshorten the possibilities of an answer. For example, most of us are at least politically aware of ‘sexist' language as it precludes the recognition of equality in a democratic society. If we speak as though all human beings were male, we are speaking an alienating dialect. Similarly, there is the often implicit racism of many (all?) languages. Further, the current revulsion against the flat, quantitative, purely economic description of society, so favoured in modern politics, demands a more humane communication. Others note with alarm the increasing robotisation of human language, evidenced in such terms as stimulus and response, conditioning, input and output, turned on and switched off, being burned out or blowing fuses, doing one's thing, or being programmed or brain-washed, developing in cycles or stages; possessing ‘magnetism', the right chemistry, or even the right image, and so on... There is the obvious danger of linguistically replacing the total range of consciousness with the model of the machine, of the computer, of chemical or physical interaction.

It is reported that an Innuit language has twelve words for snow, and that Arabic has nine words for camel. Some Australian Aboriginal languages have some nine or ten words for water. Seemingly primitive languages have dozens of ways of addressing the personal other, in contrast to the all-purpose ‘you' of modern English. How much we do not notice because we cannot word it is a matter of surmise. Languages can indeed blind a culture to various degrees of whiteness, or to varied features of camels, to the various qualities of water, or to the varying degrees of interpersonal intimacy. And to the mystery of the human itself...

Though the limitation of language (s) remains a concern when talking about ourselves, it is not the main problem. The real concern lies in the deep language, the culture out of which these languages emerge and in which they communicate. The more one's culture is numbed and stunted in its humanity, the more it deadens any capacity to word the whole range of human experience. It is as though there is nothing there to be said. Words like ‘humility', ‘mercy', ‘sin', ‘chastity', ‘adoration', ‘God', ‘creation' become verbal gestures to the quaint propensities of another age. And yet the words of the poet, the cadences of great music, the silence of the mystic, the radiant witness of moral achievement intimate, in their different ways, a ‘nonetheless. The embarrassed or inarticulate silence can be broken. The ‘narrowspeak' of our daily discourse can be refreshed with the ‘wholespeak' which addresses our hearts and imaginations.[4] There is an inexpressible more, an excess, to challenge our glibness, to turn statement to question, to make our silences meaningful, to edge us more surely into the presence of that strange reality, described by each of us, as ‘I am...'.[5]

To be human is to be nourished and clothed and worded by a particular culture. But what if that culture is distorted, stunted … gone wrong in some way? What kind of self does it give us to live? Take this example. It is often alleged that the human has been monopolising all our historical attention to the exclusion of the integrity of the natural world. Thus, ‘anthropocentricity' is the ecological sin. What is that saying about our culture? The following are possibilities. If a culture communicates a self-description of the human merely as an unregulated exploiter of supposedly limitless or untamed nature, it is clearly perverted. If it defines the human individual merely according to his or her abilities to consume commodities, it becomes bloated, doomed to decompose in its own greed. Likewise, any culture that excludes any reference beyond the tiny scope of individual and usually instant experience, that speaks no language of either self-transcendence or of concern in regard to either the present or the future, may idle for a time in a tender form of self-absorption; but it moves ever closer to the psychopathic.

Admittedly, if a culture which sees only the problems, with no sense of a larger grace or mercy, which is no longer able to acknowledge sin or failure, it may find a fragile solace in blaming others or other times for its troubles; but that is just a step along the way to increasing depression. Perhaps in disgust, some will seek to transcend the world of problems by taking refuge in some form of mystical otherworldliness. But schizophrenia is of limited creative value. Further, any way of life that begins to prize the image over reality soon finds everyone wearing masks in a hall of mirrors. In short, any culture that systematically represses any type of experience, that prevents certain questions being raised, that reduces all values to personal preferences, is on the way to becoming a slum.

Now, if ‘anthropocentrity' means any or all of these cultural diseases, then it is clearly destructive. Such cultural distortions are what Christian tradition knows as ‘original sin'. It is at root a mutilated sense of self communicated by the culture in which one lives.[6] Sebastian Moore makes the point:

The socio-cultural character of original sin is thus evident. If original sin means treating as non-existent the dependence of the sense of man's meaning and value on the ultimate mystery, it is in society as a whole, where the human sense of man's meaning and value are stored, expressed in institutions and in the whole cultural achievement, that we shall expect to find this non-acknowledgement, this conspiratorial silence as to the ultimate source of man's sense of meaning and value. Original sin is the universal and socialised withdrawal of man from the mystery on which he continues to draw his meaning and value. Original sin is the socialised truncation of human life, the systematic reduction of the child of mystery to the banal world of man's own making. [7]

3. A Classical Definition?

The ancients described the human as zoon logikon, animal rationale, literally, ‘the thinking-speaking animal'. They understood that there would be no ‘animal' unless there was a healthy vegetale component and the right proportion of minerale. Indeed, for them, ‘proportion' and ‘component' are not exactly the right words. In fact, we find an instructive dispute amongst the philosophers and theologians of our premodern times on how the ‘souls' of other forms of mineral, vegetal and animal existence were contained in the human soul.[8] What they all agreed on was that the human spirit essentially contained these dimensions in its constitution. Aquinas could say, out of his conviction that the human self was essentially embodied, anima mea non est ego, roughly translatable, as ‘My soul is not the whole of me'.[9] The human self was more than the purely spiritual. It was understood to be truly embodied in matter in a way far more intimate than modern imagination or philosophy usually credits.

True, such a conception of the human concentrated on the rationale, the uniqueness of the spiritual dimension. The intellect and will were the supreme powers of the distinctively human soul. A philosopher such as Aristotle could say that ‘the soul was in some way all things': what is distinctively human is the potential outreach to everything in knowledge and love. The human was the eminently relational. Understandably, this expansive relationality was the special domain of theology. Not only did we human beings have a relationship to all that is within the universe, but also to the all-originating principle that is the beginning and end of all that is, was, or could be.

Though such a synthesis had its own classic power in emphasising that the macrocosm was somehow embodied in the human microcosm, the history of thought shows frequent distortions. Human reality was no neatly defined ‘nature' in this philosophical sense. Spiritual writers generally reverted to a Platonic understanding of human existence. Sense-bound passions and worldly distractions were identified with the animal genus of our existence, while the true spirituality was associated with the specific rationale of our nature. As the essential embodiment of human existence was downplayed, the specifically human was conceived of in a more and more immaterial a fashion. As a result, the truly human drew closer to the domain of ‘pure spirits', to feel itself exiled on the earth while awaiting an ever-deferred spiritual fulfilment in a realm beyond. The pluriform nature of human existence as embodied spirit was slowly reduced to the awkward dualism of body and soul.

Today, Aristotelian-Thomist anthropology has, at best, retired to the status of a classic source, as we look for a more holistic self-definition. How much has changed is evident in the perceived quaintness of the classical terms once employed in defining the human: ‘animal' has become something of an insult. And ‘rational', having lost the contemplative expanse of its original meaning, is now heard almost as a taunt, implying either a desiccated logic, or an intellectuality that has forgotten how to feel for anything not contained in a laboratory or a mathematical formula. Such terms jangle in modern sensibility as shards of broken meanings.

With the advent of a more empirical approach to the human phenomenon, philosophical talk of natures has yielded to experiment and observation. The universe of definable natures, in terms of the genus and species of classic thinking has had to come to terms with the human as a manifold datum, in its varied cultural contexts, and within an evolutionary world. It was difficult to catch up with the transition, in a world ‘in which everything has changed except our way of thinking' (Einstein). Clearly, we need to be far more sensitive to the broader issues of culture which so deeply affect the way we understand our humanity. A ceoncept of the human today has to incorporate a new sense of embodiment in the cosmic, biological, social process of time and history. This suggests a search for a new spirituality in which the irreducible specifics of human consciousness will be respected and enlarged. More particularly, the challenge is one of bringing matter and spirit into a new human unity. Consciousness cannot be left schizophrenically unrelated to the world, just as that world cannot be considered shut against the most mysterious of all phenomena, human consciousness itself. Dualism, the house divided against itself, is recognised as the danger to be avoided.

The modern discussion has shifted from a philosophical definition of the human to a far more concrete exploration. Human culture in all its actual varieties, and human history as the theatre of human self-determination, are at the forefront of any reflection on the human. The notion of a determined, universal ‘human nature' has receded into the background, as a question indefinitely deferred until all the data are in. It can only become a question within the meanings and values that inform given cultures. It only arises as a question when our accelerated history makes time to consider it.

What is most obvious is that culture and history are expressions of what has been called, ‘man's making of man', of a profound or shallow, or a broad or narrow, self-expression. This self-making is embodied in the symbols, the language, the art and the institutions, the technology and the inherited traditions governing human communication. Each of these elements, in its own way, objectifies and transmits a certain sense of the human in terms of what life is, or might be, all about.

Every culture expresses a peculiar specialisation. For example, Australian Aboriginal culture, while it may well be classified as primitive in terms of technological prowess, is now newly appreciated as far wiser than it was possible to consider in the intellectual arrogance of Enlightenment period of colonisation. The capacities of Aboriginal culture for long-term survival are freshly valued. For we now live with the embarrassed realisation that the myths of mere progress offer no real future.

Part of the present problem is the intense irritability modern men and women feel, plunged as we are in often extreme and always competing human expressions that constitute contemporary pluralism: the ‘multiculturalism' of cosmopolitan democracies, and the startling variety of differing life-styles. If society is not going to be subject to progressive disintegration, some kind of fundamental commonality has to be achieved. The alternative is the endless dialectic of point-scoring ideologues, as the various ‘silent majorities' stand impotently by, disaffected from the whole cultural or political process. As the poet predicted, the best lack all conviction while the worst are filled with passionate intensity (W. B. Yeats).

4. A New Science of the Human

The only recourse is to come to new self-possession. The issue is one of owning, or even ‘owning up to', our existence in a more inclusive and imaginative way. It is a matter of being aware of ourselves as both as embodied in the cosmos, and in the indefinability of our spiritual being.

Only comparatively recently has science has begun to pay specific attention to the human. The peculiar complexity of the human phenomenon was lost in other considerations. But the hundred organs, the two hundred bones, the six hundred muscles, the billions of cells, the trillions of atoms which somehow conspire to constitute our embodied selves are a phenomenon calling for extensive exploration. Scientific exploration has moved with exquisite sophistication into the very large and very small dimensions of reality, to leave the quasar and the quark more easily named than the human self. Science, it seems, is more at home in the intergalactic than in the interpersonal. It is more familiar with sub-atomic indeterminacy than with human freedom and human destiny. Though chemistry and biology have dealt with the molecular and genetic structures of living things, they have paused, comparatively tongue-tied before the complexity of the human phenomenon. It has been easier for the scientist, as for us all, to avoid eye contact with another human being, to ask what mystery has awoken in the consciousness we have of our selves and others. It was perhaps safer to leave the human simply classified as one of the millions of species on this planet.[10]

As the physicist Heinz Pagels has noted, matters have now begun to change. The study of the complex human phenomenon, especially in the reciprocal relationships of mind and matter, will be ‘the primary intellectual challenge to our civilisation for the next several centuries'.[11]

Partly because the human is so physically insignificant in the known cosmos, partly because of the scientific fiction of totally ‘objective' observation, scientists seldom notice the most surprising phenomenon. The operation of their own minds is the most refined and complex reality the physical world has yet produced. In charting the size of the universe or the buzzing intricacies of the sub-atomic world, in tracing the organic mechanisms of life, or in considering the genetic interrelationships existing between all living things, the human mind catches itself in an astonishing act. As it knows and explores the universe, it is part of that universe. And the universe, so known and further explored, becomes progressively luminous to itself in human consciousness.[12]

The business of science has typically been so taken up with non-conscious objects, usually as they emerge out of our past, that it tends to be distracted from the luminous occurrence of the conscious present. But in this elusive, unobjectifiable now, scientific intelligence, to say nothing of artistic inspiration or mystical experience or ethical action, is in operation. One must lament that scientists too often leave themselves out of consideration. As Langton Gilkey adroitly noted, ‘If Carl Sagan is referring only to the exteriority of nature when he insists that the cosmos is all there is, he is clearly wrong: there is also Carl Sagan looking at the cosmos and trying to make sense of it'.[13] The most significant happening in the universe is going on behind the eyes of the observer. In the one and half kilograms of brain matter, it is estimated that there is more operational complexity than in the whole of the Andromeda galaxy. There are a trillion neurones of the human brain, each cell of which communicates with at least a thousand others. That would mean that the number of possible associations might exceed the number of atoms in the known universe. [14]

In this regard, we need to respect a kind of twofold movement. The Aristotelian dictum, ‘causes can affect one another, but on different levels' (Causae sunt ad invicem causae sed in diverso ordine) is looking to a larger application. Scientific exploration has been largely concentrated in determining causality ‘from below upward'. The physical, chemical, botanical, zoological realms are progressive approximations of the manner in which human consciousness has emerged on this planet. This movement poses its own questions. Where does this emerging ‘we' go from here? What are we to do in, and with, nature come to consciousness in ourselves? What are we to do with our souls?

But there is also a second, comparatively neglected movement ‘from above down-ward'. Human consciousness, in the transcendent fulfilment of faith and love, in its scientific, artistic and ethical capacities, in the whole cultural structure of its history, is at the point of making a fresh appropriation of its cosmic and biological origins. What we are as human is caused by what has gone before, but also can now influence what it has emerged from. This, too, poses its range of questions. What value do we need to put on this process of emergence? What responsibilities of care now engage us to respect the physical, chemical, biological values that underpin our well-being and cultural development? How are we to care for the earth as the shared body of our co-existence? It is, thus, a matter of reflecting far more deeply on the hylomorphic inheritance of philosophy, to explore, in a wider range of reference, both the manner in which matter looks to progressive animations by spirit, and that manner in which the human spirit is natively embodied in matter.[15]

The soul-values such as meaning, truth, morality, religious faith motivate personal development self-transcendence. If these are to flourish they need now to be re-connected with the ‘material' values out of which human life has emerged. A more conscious realisation of our embodiment is called for. The human self has to be re-immersed in the physical, chemical, botanical, zoological processes that underpin the emergence of the distinctively human world. We read in the life of Berlioz that one day, on a visit to Rome, he fell into the Tiber. To the amazement of his companions, he surfaced, singing a refrain that had long eluded him.[16] The dripping composer is an image of our present challenge: to fall into the stream of physical reality in order to recover the full symphonic sense of our existence. On this subject, George Steiner's remarks on music are deserving of mention:

No epistemology, no philosophy of art can lay claim to inclusiveness if it has nothing to teach us about the nature and meaning of music. Claude Lévi-Strauss's affirmation that ‘the invention of melody is the supreme mystery of man' seems to me of sober evidence. The truths, the necessities of ordered feeling in the musical experience are not irrational; but they are irreducible to reason or pragmatic reckoning. This irreducibility is the spring of my argument. It may well be that man is man, and that man ‘borders on' limitations of a peculiar and open ‘otherness', because he can produce and be possessed by music.[17]

Steiner cites the words of a Renaissance philosopher of music, Gioseffo Zarlino, in his judgment that music ‘mingles the incorporeal energy of reason with the body'. Even the melancholic Schopenhauer considered that ‘music exhibits itself as the metaphysical to everything physical in the world... We might therefore just as well call the world embodied music as embodied will'. Music incorporates a sense of reality as a symphonic promise. It is an elemental consolation for the human heart, and a suggestion of an inexpressible excess.[18]

While I am in no position to take this insight further, it does tease us into a more symphonic appreciation of our being in the world. We are being invited into a more disciplined attention to the embodied consciousness that each of us is - the somebody that is existing here and now. Neither you nor I are an inert lump of matter, nor a pure spiritual consciousness cut off from material conditions. We are in fact a strange inter-relationship between the two, a play of harmony, an elusive melody as a variation in a larger symphony.

For instance, we cannot think unless through some intimate connection with what our physical senses have seen, heard, tasted, felt, smelt. Even the most basic sense knowledge presupposes the more or less smooth functioning within us of a thousand physical, chemical, biological, and anatomical systems in us. To that degree, we are a system of systems, a form of existence subsuming many other inter-related and interconnected forms of being. But as we touch, taste, see, hear, imagine, think, love, work, pray, and express ourselves in work and artistic creation, we are a living whole. We are each a self in the process of becoming. Our multi-relational identity achieved in going beyond itself in relation to the all, the whole, the other and the ultimate. The axiom of ancient philosophers that spoke of the soul being somehow ‘all things' in its capacity to know, has now to be complemented by a realisation of the incorporation of our bodily being in the ‘all things' of the cosmos itself. Teilhard de Chardin perceptively remarked:

My own body is not these or those cells which belong exclusively to me. It is what, in these cells and in the rest of the world, feels my influence and reacts against me. My matter is not a part of the universe that I possess totaliter. It is the totality of the universe that I possess partialiter. [19]

All this is to say that complex levels of interconnectedness fuse and focus in the concreteness of human being. If we are to cultivate a new inclusive sense of human integrity, it will be literarily ‘of vital concern' to recognise this symphonic complexity.

5. Self-Transcendence in an Emerging Universe

‘Self-transcendence' is a good model to assist a more complete understanding of our existence. It is not primarily a philosophical category, nor is it an element in scientific theory. It is more an self-image working to integrate what is occurring ‘in action'. It suggests that the immediacy and momentum of actual living. It evokes the flow and expansion of consciousness constituting our communicative being in the world. A process of becoming, of going out of the self, in the direction of what is other and more, characterises authentic self-realisation. In a word, self-transcendence is the structured, conscious momentum of life as we experience it.[20] For example, our senses place us in an environment. Our intelligence awakens to a field of forms and meaning. Our capacities to reflect and judge make us trustworthy mediators of the real world. Our feelings for the good, and our responsible decisions move us into a collaborative world of moral value. For people of faith, God's gift of love places them in a universe of ultimate meaning and worth.

Regrettably, the dynamism of self-transcendence is not infallibly realised. We can be distracted from the attentiveness our senses make possible. We can avoid the questions that intelligence suggests. We can shut out the weight of evidence. We can prefer self-gratification to moral responsibility. We can opt for self-enclosure against the self-surrender that faith inspires. Still, the invitation is insistent: to go beyond self-imposed isolation into participation in a universal event. We ignore that summons into that world of meaning, value and ultimate grace at the peril of denying our true selfhood. An uneasy conscience is the most intimate witness to that possibility.

We must consent, therefore, to the dynamics written into our conscious being. Already we are living selves, ecstatically related to a larger whole. Teilhard de Chardin places this drive to self-transcendence in the widest possible context:

Man is not the centre of the universe as once we thought in our simplicity but something far more wonderful – the arrow pointing the way to the final unification of the world in terms of life.[21]

To be human, from this point of view, means being progressively immersed in a universal process of becoming and communion. Current cosmology and natural sciences have been remarkable in isolating the dynamic pre-personal structure underpinning distinctively human self-transcendence. The evolutionary paradigm discloses an upward pull, a ‘vertical finality', a ‘genetic throbbing' within the universe in the direction of life and consciousness.[22]The ‘non-' in the designation of the new sciences and methods (e.g., ‘non-equilibrium'principles, ‘non-linear' dynamics, ‘non-entropic' structures) points to a search for a language appropriate to the wonder of universe as it emerges in the contemporary consciousness. The range of related sciences and methods is of great complexity and sophistication: non-equilibrium thermodynamics, synergetics, hierarchy theory, autopoetics, general systems theory, fractal geometry, catastrophe theory, cellular automata, non-linear chaotic dynamics. What is remarkable is how these new kinds of exploration converge. They present the emergent cosmos as a single wave, gathering into unique intensity in the human, in an ocean of undular being. Human consciousness crests in a ‘waving universe'.[23]

So great a consonance is there between human consciousness and the matter of the cosmos, that one scientific writer, Danah Zohar, in The Quantum Self [24] has used analogies drawn from the subatomic quantum realm to further an understanding of the human consciousness in its individuality, creativity and manifold relatedness. Doubtless, many aspects of such an imaginative project will remain arguable. The valuable point of such efforts consists in linking human consciousness in some way to the intricate dynamics of a mysteriously relational quantum world. It shows that we are coming to recognise our elemental cosmic location in ways that have never been thought of before.

The point of such efforts, anthropomorphism aside, is to locate the distinctiveness of the human in the subatomic dynamics that quantum physics is exploring. Our immersion in the physical processes of the universe is recognised as a positive human value. Such is an index of the radically new self-appropriation offered to us as we find the fundamental movement of our being inscribed in the most elemental dynamics of matter.[25]

Still, there is an even larger complexity. Levels of living and non-living things exist below and before human consciousness in a hierarchical scale. They are related to one another not as closed but as open systems.[26] Whilst each level has its own laws and schemes of recurrence, there are instances of randomness, openness, even of ‘chaos' even, as entropy is dissipated, and possibilities of higher realisation occur. Each level looks beyond itself in its own kind of self-transcendence. Sub-atomic particles assemble themselves into the elements of the periodic table. Chemical elements come together into increasingly complex compounds. These structure enzymes and acids to form the living cell. Cells come together in all the variety of plant and animal life. These, in turn, are subsumed into the astonishing emergence of the human brain in the human body, just as they enter into the ecological system of the whole human life in the food we eat, the air we breathe, the water we drink, the wine of our celebrations...[27] Now this is far from a world of fixed and static natures more or less blended or juxtaposed. What emerges is more a kind of participatory interlinking of all levels of reality in our constitution.[28] Human consciousness becomes cosmic. The universe is conscious of itself in the human body, mind and heart.

Attending to the dynamic datum of human consciousness cannot, therefore, ignore the laws of physics, chemistry and molecular biology written into our emergence. Though theology concentrates on the ultimate self-transcendence of the human person in regard to God, it cannot disregard the activity of phenomena on prior levels, in the complex relationality of atoms, neurones and DNA molecules, cells, organs, organisms, bodies, bondings, populations, eco-systems... At each step, a higher possibility is preformed. Without such successive integrations, there would be no higher self-realisation. Arthur Peacocke gives a useful summary:

There is a continuous spectrum of levels in the total human unit, and these need to be addressed by language appropriate to the level in question. The reason all these languages, whether scientific or theological, ought to be able to communicate with each other is precisely their reference to this objective reality and unity of human beings, to which science and theology bear witness.[29]

6. Seven Levels the Human Good

I will now list some seven levels that dynamically structure human existence. Unfortunately, a pitifully schematic exercise such as this leaves so much out. Indeed, a number of further divisions and subdivisions should ideally be added. On the other hand, such a list is sufficient to generate libraries of questions relevant to this historical phase of exploring what it means to be human.[30]

1/ The Physical Level

In an ascending order there are, first of all, the physical elements and dynamics of the cosmos. In accepting the physical ‘forebears' of our existence, we define ourselves into the fifteen billion year old story of the emergence of the universe. Whatever the ideological differences that divide the human community, that enormous expanse of time, with all its blazing energies, is our ‘common era'. Our common clay is now stardust, whether we be human, mineral, plant or animal. A great inclusive ‘we' extends through an indescribably vast, energy-laden flame of cosmic emergence. The whole unfolds as an all-inclusive, self-organising process. Our shared present is implicit in the initial fireball of our cosmic origins, as it unfurls into a billion galaxies, and condenses into the elements which at this moment are firing the energies of our brains and the beating of our hearts, in all our happy capacities to wonder and to hope.

Science has sharpened its vision to detect the light that irradiates everything. The COBE satellite first gave human eyes the sight to peer back fifteen billions years to their cosmic beginnings. We are the first generation to have that kind of empirical view of the origin of the universe, thereby to locate ourselves in the universal process. Such is the prelude to any appreciation of the amazing creativity of our own planet Earth. To look back those four and half billion years is to witness a vast cauldron of activity in which the elemental chemicals were brewed. As such elemental matter slowly cools to crystallise and condense, it combines and complexifies until that point where primitive life emerges in the oceans. Out of these oceans come, in their time, creatures of the shore, of estuaries and marshes, to spread eventually over dry land, to take root in the soil, to float or fly in the air, to move on paw or hoof or foot in their various habitats, and thus to occupy the planet. Finally, there comes the human as the ‘the latest, the most recent extravagance of this stupendously creative earth'.[31]

2/ The Chemical Level

Implied in the above remarks is the necessity of owning also the chemical values of our existence. Phosphorus formed in the heart of the stars gives us the skeletons that structure our bodies. The stellar iron enters our blood. The sodium and potassium that drive signals along our nerves are part of a larger message. The cosmic flame of hydrogen burns in our brains. Carbon molecules fuel our metabolism. Our lungs breathe an inspired past.

But if the chemical balance so patiently achieved in the emergence of our planet is skewed by violent interruption, the water is polluted, the air begins to carry poisons, the sunlight is dimmed by smog. All life suffers, to become blighted in its fundamental systems. The one hundred and sixty billion tons of carbon spewed into the atmosphere by modern industry over the last century and a half has made a difference; it is registered in the temperature of the earth. The boon of modern refrigeration has become a mixed blessing as chlorofluorocarbons begin to change the nature of the atmosphere itself, even the quality of the sunlight, as the ozone layer is ominously holed. As the monocrops of modern agriculture cover huge farming areas, the precious topsoils that took millions of years to form are eroded, to be blown or washed away.

To be human is to be chemically linked to the earth and the cosmos itself. Earthy questions arise. The most obvious bears on the nature of the food which the earth offers for our sustenance. How is this affected by artificial additives, by the Fast Food industries of our day? For some forty years, problems associated with pesticides and food additives have been increasingly recognised. Carcinogenic has become, literally, a household word, and the easy availability of ‘junk food' continues to be a sign of progress, even as obesity in ‘developed' countries becomes a problem of remarkable proportions. But so deeply are chemically questionable practices embedded in the huge agribusinesses and food chains underpinning much of the world's production, transportation, preparation and marketing of food, that even the most cursory indication of the ill-effects sounds dangerously subversive. Given the scale of chemical distortions of organic life, synthetic hormones and addictive drugs, how long can this experimentation with human well-being be tolerated? A reclamation of our earthly chemistry is the only way to avoid long-term degradation in our bodily and psychological makeup.

Then there is the question of waste disposal and how it affects the chemical integrity of the land and waters. How many flush-toilets can the earth sustain? The diabolic project to live apart from nature has to be replaced by a metabolic location with and within nature. Thomas Berry, CP, gives an incisive summary of the situation:

The issue now is of a much greater order or magnitude, for we have changed in a deleterious manner not simply the structure and functioning of human society: we have changed the very chemistry of the planet, we have altered the biosystems, we have changed the topography and even the geological structure of the planet, structures and functions that have taken hundreds of millions and even billions of years to bring into existence. Such an order of change in its nature and in its order of magnitude has never before entered either into earth history or into human consciousness.[32]

3/ The Botanical Level

Much of what has been said above is relevant to this level as well, in terms of the quality of the food, soil and air of our planetary life-support system. But two further considerations are suggested. On this botanical level, we enter the domain of living things with whom we are companions in a planetary symbiosis. First, it is a world of beauty. Trees tower above us and blossoms fill the air with fragrance. Flowers delight the eye and great forests are wonderfully alive. To be without them is not humanly imaginable, but in vast areas of the planet, both vegetation and the human spirit are wilting under the onslaught of soul-less exploitation. In the beginning, we were meant to live in a garden.

Brendan Lovett expresses a second point:

Further important insight gained into the human good at this level relates to the diversity of plant species. The minor issue here is the destruction/loss of local varieties of seed in favour of high-yield hybrid varieties. The latter are notoriously vulnerable and do not breed true. The major issue is the wipe-out of millions of years of nature's crucial survival experiments under the most demanding climatic conditions that is involved in the annihilation of the tropical rainforests. We are destroying the gene-pool of successful wild varieties of plants at exactly the same time as we are placing the world at risk, foodwise, through reliance on climatically highly vulnerable hybrid varieties.[33]

That puts it well. We are faced with a strange choice: a living, breathing world of healthy variety, or something far inferior.[34] Questions arise: how much interference can our planetary well-being and health tolerate? How much risk should we incur in modifying biochemical structures? What is happening to the basic ‘food chain' of biological life on this planet? ‘The Great Chain of Being', beloved of philosophical tradition, corrodes in its biological links if the food chain is polluted. At this crucial juncture, human beings are challenged to live less diabolically and more metabolically with the earth. Christians celebrate the eucharist as the body and blood of Christ made present in the shared ‘fruit of the earth and work of human hands'. But what if the bread and wine are contaminated?

4/ The Zoological Level

To be human at this level is to be ‘animal' with the animals. Humans turn to animals not only a resource, but for companionship, with both the wild and the tame. We befriend nature in our pets, contemplate it in the wild, harvest it for our food, harness it for our purposes. We are the species that names the animals. Ideally, like Noah, we construct the ark for their preservation, irrespective of their immediate usefulness.

Here I will make a longer remark, and a surprising one, at least to the modern mind, long oblivious of the generic ‘animality' of our human condition. Here, we can be instructed by the science of socio-biology, for there is much to be learned and reclaimed in human behaviour by setting ourselves in the evolutionary emergence of the animal. We need recover the animal in us if we are more adequately to understand ourselves. The details are subject, of course, to wide ranging debate. But balanced perceptions are beginning to emerge. We are not ‘disembodied intelligences tentatively considering possible incarnations', but concrete embodied human beings with ‘highly particular, sharply limited needs and possibilities'[35]. Our capacities to bond, to care for our young, to feel for the whole group are rooted in our evolutionary animal nature. As Mary Midgley observes, ‘We are not just like animals; we are animals'.[36]

The acceptance of our animal nature counteracts the prevailing liberal conception of the human person as a detached intelligence, living in an isolated, self-sufficient individuality, jealously asserting, it may be, one's own rights against all others. Our kinship with the animal realm presents a healthy challenge to any theology of universal love which might tend to be excessively ethereal and unaware of inherent limitations. Our animal nature presents us with a priority of feelings and actual bondings that demand to be respected. For Thomist theology with its doctrine of the ordo caritatis (the order of preferential love),[37] there is nothing odd in such a conception. However, the drawback in Aquinas's account of the integration of natural relationships into supernatural love is the Aristotelian biology on which it was founded. The most notable deficiency in such an inheritance was its reduction of female role to a purely passive and receptive one in the generative process.[38] But progress has been made. The theologian, Stephen Pope, appeals to socio-biology as it locates social and cultural behaviour in the dynamics of biological emergence. He suggests that, by reclaiming in a more scientific manner our kinship with animals, human beings are helped to establish the order of personal relationships among themselves, even on the level of the theological virtue of charity. I summarise his conclusions as follows:[39]

First, sociobiology helps us to view human love within a much larger temporal and spatial context. The integrity of our relationships is to a large degree founded in our evolutionary heritage. Love is not a purely preternatural disposition. It is something bred into us through the dynamics of evolutionary survival and development. This understanding helps theologians both to diagnose the roots of anti-social behaviour, and to uphold the integrity of nature to be ‘healed, perfected and elevated' by grace.

Secondly, by owning our place in an evolutionary biological world, we are less inclined to think of the human self as a free-floating consciousness. We are embodied in a biological dynamic and inheritance. Our loves and relationality have a biologically based emotional constitution. They are shaped in a particular direction by the genesis of nature. There are ‘givens' in the human constitution; and as such, they precede freedom, and can never be repudiated, unless it be at the cost of denaturing ourselves in a fundamental manner. For instance, we do not live in an asexual or unisexual biological world – a point which critical feminism must continue to explore. Neither culture, nor spirituality, is all.

Thirdly, primary relationships to family, friends, community, society, need to be recognised in their particularity as priorities in our concerns. We belong to the whole human family through a particular family. We enter the global community by being connected to a special place and time. Transcendence is possible only by way of the given limits.

Fourthly, our sociobiological context helps us not only to understand, but to justify priorities of concerns. What St Thomas discerned as an ordo caritatis, an ordering of love, founded in our natural bonds and relationships, is, to a great extent, ratified by this kind of evolutionary science.

Fifthly, the flowering of altruism in a social virtue and the love of our neighbour as an evangelical imperative are founded in the kin-preference derived from our animal nature. We are naturally bonded to a species, instinctually aware of the larger group. Sociobiology shows how the most all-embracing love is the confirmation of our biological nature, rather than its contrary. It is not a foreign imposition. Grace presupposes nature. Through our common animal descent and genetic inheritance, innate affective and other-regarding orientations are bred into us.

Sixthly, such a common genesis provides a basis for not only an ‘emotional realisation of the unity of mankind' (Scheler), but also for a deep sympathy, in the strongest sense of the word, with the whole community of living things. The other is not first of all a rival or a client, nor a possession or a resource, but a companion in the unique community of life on this planet.

All this is to argue that ‘We are incurably members of one another'[40]. How deeply this is so is further evoked in Lewis Thomas' imaginative reflection. It can serve as both a summary of what has been said, and an anticipation of the next point:

A good case can be made for our non-existence as entities. We are not made up, as we always supposed, as successively enriched packets of our own parts. We are shared, rented, occupied. At the interior of our cells, driving them, providing the oxidative energy that sends us out for the improvement of each shining day, are mitochondria, and in a strict sense, they are not ours. They turn out to be little separate creatures, the colonial posterity of migrant prokaryocytes, probably primitive bacteria that swam into ancestral precursors of our eukaryotic cells and stayed there. Ever since they have maintained themselves and their ways, replicating in their own fashion, privately with their own DNA and RNA quite different from ours... without them we could not move a muscle, drum a finger, think a thought. Mitochondria are stable and responsible lodgers, and I choose to trust them. But what of the other little animals, similarly established in my cells, sorting and balancing me, clustering me together? My centrioles, basal bodies, and probably a good many other more obscure tiny beings are at work inside my cells, each with its own special genome, are as foreign and as essential, as aphids in anthills. My cells are no longer the pure line entities I was raised with; they are ecosystems more complex than Jamaica Bay. I like to think they work in my interest, that each breath they draw for me, but perhaps it is they who walk through the local park in the early morning, sensing my senses, listening to my music, thinking my thoughts.[41]

5/ The Vital Level

There can be no dance or art, no play, no creativity in thought or faith unless there is a basic health and wholeness in the human body and mind. To opt for high cultural values, even religious ones, or to commit oneself to some form of ecological care without a proportionate commitment to the human values of health and well-being can result in disaster. The dramatic situation of world poverty and the incidence of disease, eg., the HIV virus, calls forth an enormous effort of care for the undernourished on the one hand, and for the sexual nature of our existence, on the other. There is not much of a prospect for creativity in history if the rising generations are hungry, ill, and a prey to sexually transmitted disease. Physical, sexual, nutritional and hygienic education are a fundamental concern without which the human project and its healthy metabolism with the earth would collapse.

Physical, chemical and biological values must enter into a renewed religious vision. Such values motivate a deeper and more rounded ecological concern. They also provoke a more intense wonder regarding the Providence working in the whole process which, seemingly against all odds, has brought us and this world into being. The ‘higher purpose' of older considerations of the world is now illuminated as immanent in the unimaginably intricate and inter-connected dynamics structuring the cosmic gestation of life itself.

The following astutely formulated principle can serve as a bridge between what we have said so far, and the observations that will follow:

An environmental setting developed over millions of years must be considered to have some merit. Anything so complicated as a planet inhabited by more than an million and half species of plants and animals, all of them living together in more or less balanced equilibrium in which they continuously use and re-use the same molecules of soil and air, cannot be improved by aimless and uninformed tinkering. All changes in a complex mechanism involve some risk, and should be undertaken only after careful study of the facts available. Changes should be made on a small scale first so as to provide a test before they are widely applied. When information is incomplete, changes should stay close to the natural processes which have in their favour the indisputable evidence of having supported life for a very long time.[42]

And closer to the point, to quote Schumacher,

There are, of course factors of production, that is to say, means-to-ends, but this is their secondary, not their primary nature. Before everything else, they are ends-in-themselves; they are meta-economic, and it is therefore rationally justifiable to say, as a statement of fact, that they are in a certain sense sacred.[43]

6/ The Social Level

The social level of the human good is articulated in the division of labour designed to produce a system promoting human welfare. The goal of such a system is an orderly recurrence of the goods and services that nourish the vital values of the community. This is, first of all, an economic consideration: access to raw materials, the subsequent production of necessary goods, their distribution and marketing. The social value of the economic system has today become the urgent question. Is it geared to the vital values of human existence, or has it lost its way in the production of superfluities or even harmful commodities? Is economics so intent on measuring everything in terms of quantity and commodity that it systematically blocks out what really counts in human well-being? The Church's ‘option for the poor', the compassion and social criticism that have found expression in Liberation Theology, all forms of advocacy on behalf of the economically enslaved, the efforts of Western democracies to provide a safety net for the unemployed and the disadvantaged, all evidence in their different ways a search for a new economic order where first things are kept first.[44]

The economic consideration, in turn, raises the technological issue. Is the technological apparatus of our society functioning to produce fundamental human goods, or has it become a trap, a prison, tending to make a healthy social system impossible? The compulsive production of automobiles, refrigerators, weapons, non-degradable plastics, not to mention the global proportions of the garbage dump necessary for the obsolescent, the disposable and the poisonous in our productions, has reached an impasse. It is an obstacle to the survival and flourishing of life.

The malfunctioning of the economic system, and the alienating influence of the technological apparatus raise, in the most urgent manner, the question of the role of a political system in the well-being of the society. In its political determinations, society ideally expresses its concern to regulate and modify the economic system for the good of all. The political good is realised to the degree it enables the participation of the whole community in the organisation of a life favourable to human culture. Its institutional arrangements are meant to ensure the rule of law and justice, thus to lift the members of society out of purely economic interdependencies. A democracy is designed to correct the dominative bias that creeps into the social structure. But when politics becomes a public relations exercise for the economic status quo, or a promotions agency for the latest technological know-how, its primary goal is forgotten. Such ever-threatening possibilities lead to a remark on cultural values.

7/ Cultural values[45]

The first thing to notice here is that cultural values are placed above political values. Politics does not tell us what we are to become; we determine ourselves. Modern feminist, pacifist, social and ecological critiques of politics keep making such a point. Politics is not the exchange of self-determination either for economic well-being or for some form of law-and-order security. In situations of national crisis, we may well consent to certain limitation of freedom. But such a temporary compromise is made only for the sake of conserving a society in crisis for the sake of an eventual re-establishment of comparatively unrestricted self-determination on the part of individuals and groups. The openness of culture and its resistance to political or economic or bureaucratic totalitarianism are ensured only by the promotion of personal and religious values. A word on each of these.

Personal value is actualised in the self-transcending personl. To put it simply, unless there are good people doing the work of the world, with courage enough to face evil, distortion and injustice with their inner resources, no system, no politics, no government will be worth much. Such institutions will merely serve the interests of the self-seeking. On the other hand, every occurrence of honesty, integrity and moral responsibility is a seed sown for the wholesale renewal of the culture. A re-occurring pattern of integrity in those who are prepared to confront the real situation, prepared to ask the uncomfortable questions and face uncomfortable facts is the backbone of cultural health. When there enough people ready to put themselves on the line in the implementation of the unpopular courses of action that long term common interest demands, culture begins to have some muscle. When these same people are prepared to opt for the common good over private advantage, the culture is in a happy state. For human integrity radiates the values that alone can animate culture as an ongoing, life-promoting movement. An isolated individual may be unable to do much. Social conditioning is strong, and the power of social evils diminishes the capacities of any freedom. The individual needs others with whom to communicate in solidarity, if self-transcendence is to be a possibility. But personal value, embodied in the self-transcendence of individuals and groups, is the soul of true historical progress. From what source is that soul to draw its energies of renewal? This question leads to the appreciation of religious value.

At the heart of personal integrity is religious value. The sustained self-transcendence of any individual or group is mightily supported if, in the depths of human ambiguities, hope in a transcendent mystery is possible. It works in those who have come to possess the peace the world cannot give (John 14:27). Their self-possession is imbued with a joy that no one can take from them (John 16:22), just as it is inspired by a love that nothing in all creation can diminish or subvert (Cf. Rom 8: 37-39). Religious value consists essentially in surrendering to the grace and demands of a transcendent love. While religious value gives an intimacy with the ultimate, it breathes a spirit of self-transcending energy into human affairs. It is a love that is ‘patient, kind, not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude; a love that neither insists on its own way nor irritable and resentful' (1 Cor 13:4-6). Instead of giving way to cynical disillusionment and resting in bitter recrimination, it rejoices in the truth, as it ‘bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends...' (1Cor 13:7-8). Religious conversion inspires a freedom that refuses enslavement to the demonic forces of the situation. It does not leave believers cowering in fear, but knows the spirit of intimacy with the healing, liberating mystery at work in the world (Rom 8:15).

Religious value is, then, a creative and a redemptive force. Its creativity is realised as a capacity to give final assurance to the trajectory of self-transcendence inscribed into every level of our complex being. It is redemptive because it offers the energy to begin where we are, to turn evil into good, to hope against hope, to re-integrate the fragmented elements of our existence into a new creation in remaking the conditions that favour life.

7. Summary and Conclusion

The interlinking levels of the human good indicate the various ways we need to value our humanity and the world of its emergence. To consider these values is to pose a more profound and complex version of the questions with which we began. On the other hand, the recognition of such levels of investigation provides the terms in which the issues of language and culture we raised might be subjected to much greater scrutiny. Moreover, the discussion of such themes as anthropocentricity and the definition of the human in classic and recent expressions can be broken down to any number of practical questions. Finally, the seven levels as here outlined can be used to illustrate the way in which the upward and downward movements present in the connected levels of our existence are inter-related and blended. The different levels of the human good expose us to the reality of how the human is embodied in a cosmic and planetary process while being, at the same time, an ecstatic self-transcendence homing to the ultimate creative mystery of it all.

And so, to conclude. If any of us undertook to write an autobiography, we might give expression to the movement of our lives as a pilgrim path to God, a way of many detours and false starts. Yet, withal, such a way maintains its momentum and draws its sustenance from our relationships with others. But the narrative of the somebody that each of us is would be gracelessly distorted if it did not recognise itself in the larger body of the generations. Each of us is part of a generation, which in turn looks back to countless others – ‘great grandparents', our forebears. Even the most researched family tree names only a tiny number of the men and women who have brought us forth. The love and courage, the struggle to survive and provide, the conflicts and the reconciliations, the language, the slow learning, the awakenings of faith and hope – all this flows into us.

Yet to halt the narrative there would be to leave out a myriad of fellow travellers, usually unnoticed, but there, humbly and simply, going along with us. True, it is not uncommon to give a little bow to these other elements as we record the love we have for our native place, for home cooking or our favourite wine, the sunshine and the beaches, the night sky, places of vacation and refreshment, for our hobbies, books, art, even our pets, for the health we enjoyed and the fresh air we breathed. But each one of these humble elements in our story is an immense and intricate story in itself. The story of the cosmos and the earth is bred into our bones, assimilated in the food we have eaten and inhaled in the air we breathe – and received in the numberless connections that root us into the larger life of the planet.

More intimately, our material world has been formed into the world of symbols through which we read and write and speak and act, to express and explore realities in new forms and in a larger scope. A comprehensive autobiography would be one of thankfulness to the scripts already written into our brains and our bodies, into our land, into our earth, into the stars, into the whole radiating cosmos. Human beings are now in a position to tell the whole story of their origins. For we exist by grace of the past. The whole has begun to speak to us from within our newly elucidated experience of what has been going on. We are being taken to a fresh frontier of wonder. Most of what we are, above all the why of what we are, the sheer fact that we are, can never be fully articulated. We emerge out of an ocean of sheer ‘iffiness', chance and contingency, in ways that the ancient philosophers could never have imagined. It is, indeed, a moment in which to adore the Providence immanent in it all.

If such a past flows into us, what will emerge from us? Cosmic consciousness turns into historical conscience, into the uneasy conscience of the present generation. The alienation of man and woman, our lack of welcome for the child, our economic marginalising of youth, the joyless irritability of our culture, the bleakness of our expectations, are all potent factors in the present. What are we handing on? What do we bequeath to the future? It is possible that we will fall toward a malice that Jesus could not envisage (Lk 11:11) – by giving our children a serpent instead of a fish, a scorpion instead of an egg; and more generally, bequeathing to the generations to come the stone of an arid and exhausted earth, instead of the bread of a nurturing and hospitable homeland. What is the prayer of our last breath as death comes to meet us out of the nature we have so long demeaned?

Human history cannot cut itself off from nature, nor is it natural for ‘nature' to swallow up human history in meaninglessness, to wipe the screen clean of human meaning in blank extinction. One cannot easily believe that evolution aims at decapitation. Yet neither does it aim at disembodiment. The historical challenge at the moment is to achieve a new embodiment, a new earthing in the planetary and cosmic process. Our reflections on the past are a form of having time for the wholeness of the history and the world that have brought us forth.

[1]. For a classic treatment on the theme of the questioning character of human existence, see Eric Voegelin, Order and History IV: The Ecumenic Age (Baton Rouge: Louisiania State University Press, 1974), especially pp. 316-330.

[2] Maximus Confessor, Difficulty 41:1305B. See Andrew Louth, Maximus The Confessor (London: Routledge, 1996) 19-33. I follow Louth's translation. See also, Lars Thunberg, Man and the Cosmos. The Vision of St Maximus The Confessor (New York: St Vladimirs's Seminary Press, 1985) 132-137.

[3]. Quoted by Gabriel Daly in his stimulating Creation and Redemption (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1988), p. 116.

[4]. See Les Murray, Blocks and Tackles. Articles and Essays 1982 to 1990 (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1990) 65-6.

[5]. See George Steiner, Real Presences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989). His argument proposes ‘that any coherent understanding of what language is and how it performs, that any coherent account of the capacity of human speech to communicate meaning and feeling is, in the final analysis, underwritten by the assumption of God's presence'. (p. 3).

[6]. For an insightful treatment of this subject, see Neil Ormerod, Grace and Disgrace. A Theology of Self-Esteem, Society and History (Sydney: E.J.Dwyer, 1992).

[7]. Sebastian Moore, The Fire and the Rose are One (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1980) 67.

[8]. See, for example, STh, I, q. 76, a. 3.

[9]. Commentarium in I Cor 15, lect. 2. Brian Davies, The Thought of Thomas Aquinas (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992) 205-217, gives a very clear presentation of Aquinas's hylomorphism.

[10]. For an abundance of wry, witty and deeply philosophical observations, see Walker Percy, Lost in the Cosmos. The Last Self-Help Book (London: Arena, 1983).

[11]. Heinz Pagels, Dreams of Reason (New York: Bantam Books, 1989) 12-13; 329. For the larger context, see Christopher F. Mooney, ‘Theology and Science: a New Commitment to Dialogue', Theological Studies 52/2, June 1991, especially 410-418.

[12] Mark Wynn, God and Goodness. A Natural Theological Perspective (London: Routledge, 1999) 150-157; 159-168.

[13]. Langdon Gilkey, ‘Science, Reality and the Sacred', Zygon 24 (1989), 294.

[14]. Holmes Rolston, Science and Religion: A Critical Survey (New York: Random House, 1987) 66; also Barbour, Religion in an Age of Science, 146-148.

[15]. Interestingly, Rupert Sheldrake, The Rebirth of Nature, pp. 83-88; 108-110, can be read as a modern re-expression of Aristotelian hylomorphism.

[16]. See Jean Mouroux, in The Meaning of Man, tr. A. Downes (New York: Image Books, 1961), 256, n. 33. He is citing J. Delacroix, Psychologie de l'Art.

[17]. Steiner, Real Presences, 19.

[18]. Ibid.

[19]. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Science and Christ, trans. Rene Hague (London: Collins, 1965) 13.

[20]. For a fuller elaboration of self-transcendence, see Lonergan, Method, 3-120; and for its cosmic and historical context, see Voegelin, Order and History IV, especially 300-337.

[21]. Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man (London: Fontana, 1966) 247.

[22]. See Brendan Lovett, Life Before Death (Quezon City: Claretian Publications, 1986) 77-97. For further illustration of this point, see Charles Birch, On Purpose, (Sydney: NSW University Press, 1990).

[23]. Arthur Fabel, ‘The Dynamics of the Self-Organizing Universe', Cross Currents XXXVII/ 2-3, Summer-Fall, 1987, pp. 195-202.

[24]. Danah Zohar, The Quantum Self (London: Bloomsbury, 1990).

[25]. For an expert presentation of the new context of discussion, see John Honner, ‘Not Meddling with Divinity: Theological Worldviews and Contemporary Physics' Pacifica 1/3 (1988), 251-272; and ‘The New Ontology: Incarnation, Eucharist, Resurrection and Physics', Pacifica 4/1, Feb. 1991, 15-50.

[26]. Rolston, Science and Religion, 22-26 and passim. For more on the ‘hierarchy of levels', Barbour, Religion in an Age of Science, 165-176.

[27]. See Peacocke, God and the New Biology, 120-127.

[28]. See Sheldrake, The Rebirth of Nature, 100-108, for another, but associated vocabulary: holons as successively ‘nested hierarchies'. At each level, the holons are wholes containing parts which are themselves wholes containing lower-level parts, and so on. For more on ‘multilevel theories', especially in reference to the work of Roger Sperry, see Barbour, Religion in and Age of Science, 198-200.

[29]. Mooney, ‘Theology and Science', 319.

[30]. Lovett, Life Before Death, 86. For further illustration, see James G. Miller, Living Systems (New York: McGraw Hill, 1978); and Robert M. Doran, Theology and the Dialectics of History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990). This latter work is one of enormous ambition; it is particularly valuable on the profound cultural shifts that are occurring.

[31]. Brian Swimme, The Universe is a Green Dragon. A Cosmic Creation Story (Santa Fe: Bear and Co., 1984) 31.

[32]. Thomas Berry, The Dream of the Earth (San Francisco: Sierra Book Club, 1989) xiii.

[33]. Brendan Lovett, On Earth as in Heaven (Quezon City: Claretian Publications, 1988) 23-25.

[34]. A large problem is brewing for us beef-eaters in the more privileged parts of the world. There are 1.28 billion head of cattle on the planet. We note that only 11% of feed goes to produce the beef itself. Cattle in feedlots produce, by consuming 790 kgs. of plant protein, only 50 kilograms of meat protein. This enormous consumption of food needed to produce so little in return, not to mention the clearing of rain forests for grazing land, and the degradation of existing cattle country, poses problems of seismic proportions. For an incisive treatment of this issue, Jeremy Rifkin, Beyond Beef. The Rise and Fall of the Cattle Industry (New York: Dutton, 1991).

[35]. Mary Midgley, Beast and Man: The Biological Roots of Human Nature (Ithaca: Cornell University, 1978) 71.

[36]. Midgely, Beast and Man, xiii.

[37]. The classical account is to be found in STh, II-II, q. 26.

[38]. For a balanced, but perhaps surprising view of the theology of Aquinas on this point, see Catherine Capelle, Thomas d'Aquin feministe? (Paris: Vrin, 1982).

[39]. See Stephen J. Pope, ‘The Order of Love and Recent Catholic Ethics: A Constructive Proposal', Theological Studies 52/2, June 1991, 255-288.

[40]. Mary Midgley, Animals and Why They Matter (New York: Penguin, 1983) 21.

[41]. Lewis Thomas, The Lives of a Cell. Notes of a Biology Watcher (New York: Viking Press, 1974) 3-4.

[42]. Ralph and Mildred Buschbaum cited in turn by E.F. Schumacher in Small is Beautiful and Juan Luis Segundo in An Evolutionary Approach to Jesus of Nazareth (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1988) 39.

[43]. Again as cited in Segundo, An Evolutionary Approach, 39.

[44]. For a challenging analysis, see Herman E. Daly and John B. Cobb, Jnr., For the Common Good. Re-directing the Economy toward Community, the Environment and a Sustainable Future (Boston :Beacon Press, 1989).

[45]. For a profound treatment of the following issues, see Doran, Theology and the Dialectics.., 473-499; 527-558.