CONTENTS

Section 1 - Implications: A First Circle of Connections

Section 2 - A Second Circle of Connections: Contexts

Section 3 - A Third Circle of Connections: The Logos in the Cosmos

Section 4 - A Fourth Circle of Connections: From Within Creation

Section 5 - A Fifth Circle of Connections: Human Being

Section 6 - A Sixth Circle of Connections: The Trinity

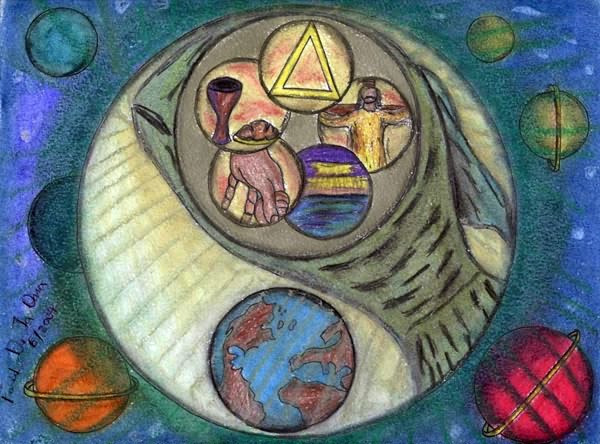

Section 7 - A Seventh Circle of Connections: The Eucharistic Universe

Section 8 - Dimensions: Death

Section 9 - Dimensions: Love and Sex

Section 10 - Conclusion

Bibliography

AN EXPANDING THEOLOGY

Faith in a World of Connections

Anthony J. Kelly CSsR

Section 1

IMPLICATIONS: A FIRST CIRCLE OF CONNECTIONS

1. A Turning Point for Christian Theology

I believe that Christian theology, by expanding to meet the demands of the age, is coming into its own as a great intellectual adventure. As faith works to express its meaning in the light of new ways of understanding the universe and in the context of a new ecological awareness of our planetary co-existence, there are plenty of splendid beginnings. Yet, at the moment, we are still at the point of inklings, anticipations, partial viewpoints in regard to what might emerge. The task ahead is daunting. There is nothing new in that. As with all emerging realities, there will be dead-ends, strange turns, long periods of puzzlement, much confusion, discouragement and sudden breakthroughs, as the course of trial and error zigzags through the range of possibilities to come to decisive insights and a larger vision. The great medieval theologians knew the burden of such creativity as they struggled with the newly available writings of Aristotle, and pored over the Jewish and Arab commentaries on ‘the philosopher', as Aquinas would always call him. But while the medieval achievement is both an inspiration and an often surprisingly fruitful resource for what is before us now, it leaves us, nearly eight centuries later, with our own distinctive challenges and opportunities.

As a reflective Christian faith slowly familiarises itself with the methods, the categories, the achievements of current explorations of the world, of life and of the cosmos itself, a definite excitement stirs in theological thinking. It is beginning to learn a new language, one more worthy of the limitless mystery it serves. It seems we are coming out of a period in which the language of faith was a very private dialect, in which ‘the light of faith' was too often experienced as a very interior, inward illumination. There were reasons for this; for we are all limited by a particular historical viewpoint. But now that dialect has a chance to grow into a means of universal communication in the measure that it can give expression to a new sense of gracious wholeness. Likewise, the light of Christ has begun to play on the whole mystery of life and to irradiate the universal scope of our knowledge of the world. In short, faith has the opportunity to express itself within a new learning curve. Our shared human search moves us toward a more comprehensive vision of the universe and of the genuinely earthly character of our existence.

Christian faith is natively a universal vision of all things in Christ. Hence it must always be looking for an adequate ‘philosophy' to articulate its real meaning in terms of the ‘all' and the fundamental meaning of the real.[1] When such a search for wisdom shares today's ecological optic, and unfolds within an expanding cosmological horizon, something new is beginning. Theology is being re-invigorated with the excitement of learning. This has already happened in terms of the fundamental documents or doctrines of faith: enormous progress has been made in biblical and historical studies. But there remains ‘the book of nature' to be read as a kind of primary revelation accessible to all.

Then, too, the expression of faith has already achieved a new comprehension of social reality in the variety of liberation and political theologies. But such modes of reflection eventually give rise to deeper questions concerned with our co-existence with all living things on this planet. Also, there is the increasing expert practice of dialogue with other religious traditions and worldviews. But here, too, we must go further. While the growth in mutual comprehension and respect are magnificent achievements, neither our differences nor our agreements can let us forget our common earthly origins and responsibilities. Moreover, the feminist turn in religious and theological awareness as the decisive advance. But there is more still: while faith can be newly converted to those religious, intellectual, moral and psychological values embodied in the unacknowledged experience of women, such values invite to a deeper, more inclusive sense of life and reality which remain to be explored.

In short, while genuine advances in the search of faith are secured in a more critical scrutiny of its primary data, in a more compassionate social praxis, in a dialogue with all peoples of wisdom and good will, in the overcoming of sexism, each of these advances can only be enhanced when set within the movement of a longer, larger, all-inclusive story – that of the emergence of the universe itself and the evolution of life on this planet. When the Gospel story is told within such a narrative, faith begins to reach down to its deepest roots in the earth; and to stretch out into hitherto unimaginable dimensions of the cosmos.

2. Faith Making Connections

In this new context, faith (not to forget hope and love) continues ‘to seek understanding', fides quaerens intellectum, as the time-honoured definition has it. Though the current context of this search is often overwhelming in its novelty, three basic and rather traditional techniques stand out as resources for a renewed elaboration of the Christian mystery.[2]

First, there is the way of analogy. By using models, metaphors, symbols drawn from experience, we move from the known to the unknown, in order to arrive at a partial but more comprehensive expression of what faith means. This is the most familiar of all theological moves. Hence, we explore the meaning and significance of the Trinity, following the paths mapped out by, say, Augustine and Aquinas, as they extrapolated from the experience of human community or human consciousness.

Secondly, theology constructs its systems of meaning by making connections between all the different articles or aspects of faith to achieve an ordered, one might say, holographic, vision of God's self-communication in Christ. For example, the mystery of the incarnation can shed light on the meaning of the sacraments; just as the eucharist, for instance, can suggest ways of understanding how the Spirit is present and active in the world.

Thirdly, theology seeks to speak to the dynamics of hope, and to the search for meaning and fulfilment. It must immerse its religious expression in the stream of humanity's common search for the fullness of life, the ultimate in human destiny. The meaning of faith is meant to be liberating, leading to a greater conduct of freedom, yet opening to that future that only God can give. The dramatic and often heroic articulations of Liberation Theology move in this direction.

In the present scientifically informed culture, such analogies, interconnections and ultimate reference need to operate in a field incredibly extended in comparison with the past. An expanding universe, an evolutionary world, a relational and holistic understanding of all reality, all demand a theology that can grow with the universe of our perception. Reflective faith, therefore, has to work with analogies drawn, for example, from quantum mechanics and evolutionary process.[3] The old views of nature, of matter, of substance, even of causality, will not do. The unchanging ‘great chain of being' that structured the mental space of past thought for millennia must now be interlinked within the processes that have occurred, and are occurring, in time.

Perhaps the deepest change in the style of analogical thinking comes in the realisation that the whole universe of reality is one great process of evolutionary emergence. While there are distinctions, hierarchies, differentiations to be observed in the given plurality of living and non-living things, all are alike inasmuch as they participate, in an interconnected manner, in the one process of universal becoming. The cosmos is understood as a vast analogical event. If analogy is knowledge made possible by extrapolating from one frame of reference to another, it is now seen, not so much as an improbable stretching of the imagination from one order of being to another, but as the only way of approximating to the concrete, dynamic unity-in-difference that the actual universe represents.[4]

As there are new resources for analogical thinking, so too there are new ‘inter-connections' to be made. The connections that faith might make amongst its own specific truths need now to be related to the world of inter-connections and communication that science has both discovered.

If new analogies recommend themselves, if there are new connections to be made, there is also a new form of universal hope to be expressed. Faith has to learn to speak of human destiny not simply out of a laudable concern to save one's soul, but in terms of the emergence and destiny of the universe as a whole. Theology is faced with its most important question: how daring and inclusive might our hope be?

In all this, reflective faith has much to learn, and in that learning, something unique to share. The light of faith is shining in a radiant universe. We can perceive a universe literally aglow with cosmic radiation witnessing to its explosive beginnings. NASA's Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite is enabling scientists to backtrack fifteen billion years to the first 300,000 years of our cosmic beginnings.[5] In a world of such stupefying dimensions of time and space, the light of faith is another kind of background radiation, gently inviting us not to miss the whole point of our existence. . . Thus, the ‘faith seeking understanding' of theological tradition is struggling for new expression as ‘faith making connections' with, and within, the ecological and cosmological understanding of our day.

3. The Theological Spectrum

The current situation of theology can perhaps be illumined by the simple metaphor of the spectrum or the rainbow. Up to a comparatively recent past, the great theological and philosophical traditions that have nourished the expression of Christian faith have tended to concentrate on one or other end of the spectrum of our experience of the reality. At the upper extreme, theology explored the ethereal indigo of human transcendence and spirituality, and the violet of the inexpressible mystery into which it fades. More recently, reflection has been concerned with the lower extreme, the red of the flesh and blood of our humanity, as it is manifest in, say, various current efforts to affirm the body or the feminine, and to face more squarely the extent of human suffering. Consequently, it has moved into the dramatic orange and gold of essential human values prized as the animating force of human culture.

Between the two extremes of the spectrum is the green of a new ecological realisation. In this middle band, the vivid colours of our history and culture come together with the blue of larger cosmic exploration, to meet in the hitherto unnoticed green. There it finds the earth and all its living systems in the great community of planetary life. This middle band of green, in its turn, unfolds into the blue of the cosmos, as into the indigo and violet of the unfinished reality that we are, and the ultimate mystery which our souls breathe.

Simple as this metaphor is, it is a way of saying that theology has begun to respond to all the colours of the spectrum. We no longer live in the old simplicities of black and white. For we find ourselves in an astonishingly vast, subtle and beautifully differentiated universe of many colours. With this new sensitivity to the variegated radiations of the light, faith can befriend the One who dwells in the radiance of ‘unapproachable light' (1 Tim 6:16) of the divine mystery; and appreciate more fully the all-illuminating light which, in Christ, ‘was coming into the world' (John 1:9).

As it unfolds into this larger, more differentiated arc of consciousness, a viridescent theology is emerging. Green has become, as it were, the linking colour, blending the precious gold of human consciousness with the overarching blue of a larger cosmic mystery. Our whole experience of reality is undergoing a ‘greening' – of the Church, of the Gospel, of ethics and morality, of science, spirituality and culture – all converging to argue, one way or another, that ‘God is green'.[6]

Metaphors aside, a new movement, a new connection, a new comprehension of the whole is taking place. Perhaps most of all, it is a new taste for life and the mystery of its origin and meaning. Faith has its own intimacy with that meaning and origin. For that reason the words of the Psalm leap out and take wing in directions that theology has to follow. It has to learn to speak to, and, more importantly, out of, the awareness of those who, with growing realism, can

...feast on the abundance of your house,

and you give them drink from the river of your delights.

For with you is the fountain of life;

in your light we see light (Ps 36:8-9).4. Faith in a Time of Complexity

Despite the fact that the ecological turn in our culture and faith seems irreversible and that the new cosmological horizon is one of limitless excitement, it is inevitable that a new range of monochrome ideologies will try to prevent the full play of possibilities. But a world radiating only green or red or blue light would eventually prove nauseous. Before long, we would be living in an anxious world of jaded, depressive grey, where the only realities are the problems, the conflicts, the failures and the threats. But it is not the time for faith to lose its nerve. For faith contains vital resources to centre and support the new turn in human awareness that has begun, but which remains vulnerable on many fronts. Even to be minimally touched by the new ecological awareness and the scale of the cosmos is to feel intimidated by the scope of the challenge. Though a certain amount of vertigo is inevitable and healthy, the newly-wakened consciousness risks becoming intoxicated, overloaded, and finally exhausted. How to keep the vision alive and the contribution positive and vital, how to grow both in hope and the joy of existence, become real issues. After all, the scale and intensity of new global responsibilities can cause ‘burn-out' of the same proportions!

For instance, as we begin to take in the proportions of the destruction that has occurred in the tiny span of recent human history, the negativities of the situation can be appalling. Add to this the tides of information that wash over our minds from the dozens of relevant sciences and the hundreds of activist groups, and we soon find that it is all too much. A meeting held in New York in preparation for the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 produced twenty four million pages of documents. How many readers were there? [7]

Obviously there is a marvellous heightening and expansion of consciousness to be had as we think of the millions of species to which we are related, sometimes, alas, destructively, in the commonwealth of planetary life; as we ponder the billions of years that have gone into the making of this present moment of shared existence; as we grow in awareness of the beauty, the fragility, the sheer chanciness of it all. Yet there is a special strain as well. The imagination unfolds into strange new frontiers of experience. We are taken to the edge of a limitlessness beyond: the meaning of it all, the wonder of life, the obscure purposes that govern the whole of existence, the directions that beckon. . . Likewise, we are come up against limitations within: how little we know and how little we can do.

To touch on such limits is to be driven back to the most sustaining sense of reality. We begin to feel a fresh need for some inclusive horizon, some solid ground on which to stand, some shareable source of energy and hope.

Aristotle averred twenty three centuries ago that the human spirit was in some way all things.[8] But it is no easy matter, psychologically speaking, to be open to the universe, especially as contemporary sciences are revealing it. The new vision not only disorientates the mind as any number of the pioneers of quantum physics confessed[9]; it disturbs the conscience as new values, new cares, new responsibilities make their presence felt. Given the complexity of the situation, any inherited meanings and values suffer a crisis. They are stretched to breaking point. Any pretended synthesis leaves so much out. We soon find ourselves adrift in problems and brought to the point of a new kind of existential panic. The danger is that we either give up in hopeless confusion, or seek an escape into a rigid one-dimensional solution. At that point, a premature totalisation of one or other aspect of the either the problem or its solution blocks further learning. Psychologically, we cease to be participants immersed in the whole emerging reality. Our minds congeal in the midst of the stream of life. We no longer go with the flow. It is then that imagination fails; and with it, the true patience of hope. We no longer have time for the whole to reveal itself. More practically, the possibilities of genuine conversation to be enlivened by the expanding range of human expertise and experience are diminished.[10]

The century past has known enough of the destructive force of totalitarian ideologies. The curse of our recent history could be turned into a blessing should we finally learn to distinguish between the inexpressible, but all-involving, wholeness of reality and particular totalitarian viewpoints. The problem with any ‘grand solution' ideology is that it works against the very realities it pretends to cherish. For instance, a scientific ideology becomes a learned refusal to learn. A socialist ideology degrades the society it seeks to serve, while a capitalist ideology ends in consuming its own economic resources. Both fascist and racist ideologies make hateful the nation or race they aim to glorify. A feminist ideology can soon exhibits all the disease of the patriarchalism and sexism it abhors. A religious ideology ends in worshipping itself rather than God.

Is it possible that ecology can give rise to its own range of ideologies, perhaps to share many of the characteristics of those listed above? The trenchant comment of a noted ecologist can be taken as a sober warning:

Vital as ‘interconnectedness' may be, it has often been the basis of beliefs ... that become the means for social control and political manipulation. The first half of the twentieth century is in great part the story of brutal movements like National Socialism that fed on a popular anti-rationalism, anti-intellectualism and a personal sense of alienation. They mobilised and homogenised millions into an anti-social form of perverted ‘ecologism' based on intuition, ‘earth, blood and folk', indeed and ‘interconnectedness' that was militaristic rather than freely communitarian. Insulated from any challenge by its anti-intellectualism and mythic nationalism, the Nationalist Socialist movement eventually turned much of Europe into a huge cemetery. Yet no one would have believed, given its more naive precedents in the intuitional and mystical credo of a century earlier, that fascist totalitarianism would have gained sustenance from such starry-eyed worldviews.[11]

All ideology is the death of hope and imagination. One all-consuming idea replaces the inexpressible manifold of our real experience. It is precisely here that reflective faith will have a critical role to play. It will have to insist that each register of human experience be given its due. As these reflections unfold, I hope that will become clear. At the moment, I merely remark that the only worthwhile response must lie in the use of our best resources:

To be very intelligent where intelligence is needed; to be defiantly hopeful where hope is needed; to be passionately loving where love is needed; to be calmly wise where wisdom is needed. Only in this way, can we contribute what we can, and humbly receive what others might give. After all, as Claudel reminds us, sometimes the worst does not happen!

5. The Point of Faith

Given, then, the ideological perils that seem to threaten from every side, there is a serious question that Christians must face. It affects so much of what follows. The question can be expressed very simply: how does faith fit into all this? The ‘this' here means the new ecological and cosmological communities of consciousness which invite religious believers to participate in such novel ranges of concern. I think a helpful preliminary answer can be found in terms of a description of faith given by Bernard Lonergan. Faith, as a knowing born of religious love, is consciousness

brought to a fulfilment, as having undergone a conversion, as possessing a basis that may be broadened and deepened and heightened and enriched, but not superseded...[12]

Human consciousness is experienced as a ‘coming to' of the self. It is the self present in everything we receive and do. We see and hear and touch and smell. Our self-presence expands to a new level as we imagine, wonder, question. It increases in its specific gravity as we ponder evidence, to get beyond impressions or bright ideas, to the truth and value of things or actions. Thus, the self is experienced as putting itself on the line. But then it reaches a special integrity in responsible decision and in the peace of a good conscience. It blossoms into a kind of ecstatic relationality as we fall in love or give ourselves over to a great cause, the experience of finding oneself by losing it.

In all these levels of expanding awareness, the self we are is experienced as a question: is there ultimate meaning to the meanings that illumine the direction of life? Is there a final sufficient reason, an ultimate confirmation for all the sufficient reasons of the truths we hold to? Does the mystery that gives rise to the universe ultimately cherish everything we treasure? Am I ultimately in the presence of a Thou in which each of us and our real world comes home?

Faith, in this perspective, is the occurrence, however dramatic or unexpressed, of a sense of Yes to the complex undertow of all such questions. Dag Hammarskjold, the former Secretary General of the United Nations, entered the following words in his journal shortly before his untimely death. They give vivid expression to the sense of faith we are describing:

I don't know Who – or what – put the question. I don't know when it was put. I don't even remember answering. But, at some moment, I did say Yes to Someone – or Something – and from that hour I was certain that existence is meaningful and that, therefore, my life, in self-surrender, had a goal.[13]

Now, while such faith cannot be superseded, while its radical, intimate, universal Yes cannot be replaced by a No, it can be ‘broadened and deepened and heightened and enriched'. This is the point at which Christian faith can expand into the new meanings and values of, say, ecology and cosmology. The basic conversion that faith is, can be broadened into whole ranges of ecological concern. It can be deepened in its contact with new cosmological understandings of the universe. It can be more collaboratively embodied in the world of human experience and exploration. Such a development, far from undermining religious conversion, enables it to expand into a new context, one more worthy, in fact, of its primary orientation and more attuned to its implicit universality.

Hence, faith continues to seek understanding. In such a search, theology becomes more obviously ‘faith making connections', and more fully an ‘analogical imagination'.[14] Such a connective or analogical imagination unfolds in its efforts to discover new analogies in which to express the focal meanings of Christianity such as creation, Trinity, Incarnation, the death and resurrection of Christ, the Eucharist and the final consummation of all things in God. Implicit in such creativity will be new ways of interconnecting such focal meanings not only amongst themselves, but within an ecological and cosmic world of inter-relationships that so occupies modern consciousness. This will lead to a more comprehensive expression of Christian hope within an horizon of planetary and cosmic solidarity. ‘Life to the full' (John 10:10) must include all the dimensions of life as we are coming to know it.

Hence, faith has both a deconstructive and a constructive role. By resisting any kind of a new ideological system in the name of its own universal vision, Christian experience is challenged to embody itself in a freshly comprehensive manner. An ultimate faith, hope and love are not irrelevant to the new holistic visions that are emerging. Far from denying the positive attainments of the new sciences, theology can work to place them in a context of reconciliation, communion and, most importantly, of hope. Even if the light of faith is experienced as no more than a kind of `background radiation' in many lives of research, art and social commitment, it still communicates its sense of the universe as ultimately friendly.

6. The Community of Faith

Christian faith is in fact showing considerable vitality with a whole range of resources to offer: theological, moral, spiritual, philosophical , along with the ‘dialogical' experience inscribed in its missionary beginnings, in its medieval synthesis, and in its contemporary commitment.[15] With its sense of creation as a whole, its sense of the genesis of the cosmos as preparation for the genesis of God in the incarnation, with the whole hope it offers, theology is working to a new relevance.

At a juncture when the human race and the poisoned earth need all the help they can get, it is as well, then, that those of us who are Christians define ourselves into the great conversation now taking place. In regard to ecological concerns the consideration of the religious dimension has entered into a more productive phase after earlier recriminations.[16]

Though we human beings differ in so many of our visions, values and priorities, there are two things we have in common at this critical moment: first, a sense of the immense, labouring fertility of the past which has brought us forth and placed us together in this present moment; and, secondly, a responsibility for the future which in some quite new way will be the product of our present decisions. A ‘common era' has been forced upon us by the sheer extent of the concerns we must now share. The imperative, for each of us and for the great classic traditions that have nourished the human enterprise, is to throw our best selves into the mix, so to speak. No one has cornered all the good energies of faith and love, of justice, tenderness and wisdom. And, no matter what way we look at the situation, there is still not enough of such spiritual energies to go around. So, we do the best we can. And that is the spirit in which Christian thinking has to proceed.

No amount of technical organisation and political re-structuring for the sake of a new society is going to be effective without a large measure of community. If there is no shared experience we will be talking about different things. If there are no shared meanings we won't be able to talk at all. If there are no shared values, we will simply populate the world as antagonists. Hence, a fundamental sense of community is the first requirement for the great creative efforts history is demanding.[17] Unfortunately, this is exactly the area where increasing alienation has ruled: the disaffection of the human from nature, and the violent disaffection of human beings among themselves, with the resulting emergence of huge blocs of competition along political, economic, racial, sexual, cultural and religious lines. Our superstructures have evolved to serve an alienated situation in which the common good was at best a compromise. When economics becomes mere monetarism, when our national GNPs measure everything except what really matters, when politics is locked in competing blocs of self-interest and greed, ecology can easily restrict its aims to uncritical environmentalism: it becomes a matter of merely tidying up the madhouse or landscaping the minefield. And, of course, huge ungainly bureaucracies keep on growing in a frenzied effort to stabilise a system that is not working.

The most available rhetorics are the liberal one of Late Capitalism with its emphasis on individual rights, and the optimistic one of a ‘new world order', now that the collectivist experiment of the Soviet Empire has expired. Such a discordant situation is hardly hospitable to a deeper sense of differentiated community based on mutual relationships of care and responsibility in regard to the life and future of the planet. There seems little opportunity for speaking realistically about a radical ecological re-ordering of the world, even if the Earth Summit of June 1992 pointed to the urgency of the situation.

In such a situation the Church has to redefine its identity and role in today's world. The traditional theological definitions spoke of ‘perfect societies' such as Church and State, just as modern democracies opted for a radical separation of these two social entities. The shared viewpoint rested on the conviction that both Church and State had legitimate, or at least realistically acceptable, spheres of influence, each with its own end in view. But these accepted divisions and separations are no longer as productive as they once were. We now live in a world in which every group is subject to a common crisis: new forms of planetary cooperation have become necessary to secure a common survival. A refreshed sense of community is now a matter of pressing importance. A profound cultural shift has become imperative.

It is here, I suggest, that the Christian churches must seize the opportunity to offer a unique service at this historical moment with their resources of moral traditions and religious vision. There is no easy way simply to legislate the structures necessary to maintain the quality of the biosphere. Even if such structures might conceivably be legally enforced, the deep values and meanings relevant to the critical situation cannot be decreed into being. Legislative bodies can change laws, but they cannot change hearts. That can only come about by an inspired new sense of community and solidarity. It is on this level, that of the deep structures of human belonging and shared hope, that Church can redefine its role.

However, this community-forming ministry of the Church can only operate within larger pursuits of planetary community. Though it is an international institution, with its own long history in the development of Western civilisation, the Church is not a world to itself. In times past, it has been the carrier of intellectual and moral values to a significant degree. But now the worlds of intelligence and moral values have expanded so much that the Church reshape itself as both a teacher and a learner in a new situation. Such is the case , not only in regard to the world of science, not only with respect to the morality of human rights, but also in a world of inter-faith contact. Hence dialogue has become the key to ecclesial development in the world in which it finds itself.

If the Church is to promote a new sense of human belonging, it cannot, of course, ignore the community of science, especially as human intelligence has inspired a new telling of the story of our cosmic and biological origins. Nor, if it is intent on speaking to the human heart can it ignore the community of moral self-transcendence, of values, of ethical integrity, in the company of all people of good will, those who recognise that global co-existence has become impossible without a demanding sense of the common good.

Then, too, there is the community of art, that domain of creativity by which our experience is freed and refreshed to perceive the original beauties that the routine concerns of life obscure and distort. For the Church, in its own way, witnesses to transcendent beauty, to the glory that has been revealed, yet too often remains concealed by the obsessive rationalism and moralising of a religion removed from its fundamental experience.[18]

More immediate to Church concerns is the community of religious faith, those who cultivate the transcendent, the holy, the ultimately worthwhile. When self-transcendence flowers to a sense of life within a gracious universe, an energy powerful in its ability to sustain the communities of meaning and moral value is at work. Here the Church makes contact with a community of ultimate connections. Within these larger collaborations and communities,[19] the Christian community forms itself in the light of its own special experience of God revealed in Christ. It lives in a world in which the divine mystery is communicating itself to the cosmos, inspiring an ultimate hope that God will be `all in all' (1 Cor 15: 28).

In this larger world of intelligence, morality and religion, the Christian Church has both a redemptive and a constructive role. All forms of community are vulnerable to the baleful influence of ‘the seven deadly sins': pride and greed, envy and apathy, violence and dishonesty remain ever apt to frustrate the possibilities of collaboration in the common good. By witnessing to its conviction that forgiveness and reconciliation are real possibilities for human existence, no matter how godforsaken the historical situation seems to be, no matter what the extent of the failure and destructiveness present in any past, the Church acts within culture to assist in diagnosing the general plight. In its witness to limitless mercy, the Christian community encourages the integrity required to confess our social sins for what they are, and to renew hope even when healing seems impossible. Without such honesty and hope, any culture is locked in an endless rationalising in regard to its deepest failures. When sins are confessed in the hope of forgiveness and reconciliation, a new beginning can be made. Hope enables us to imagine the world otherwise. For our history is not the sum total of our failures. The last word, at least in any Christian statement, is one of grace and limitless mercy.

More positively, the Church has a constructive role to play in the global and ecological turn in human consciousness. Christian faith lives in a familiarity with the universe as the one creation of God. It surrenders in adoration to that mystery of Love which created the world in order to communicate itself completely to what is other than itself. Such love is the field of life-giving, transforming energy pervading all creation. In those who surrender to it, the energy of God's Spirit inspires a totality, a uni-verse, of all things in Christ, along with an outreach to what is most forgotten, vulnerable – the suffering neighbour in whatever form she or he or it is present. Distinctively, such faith celebrates its sense of the divine presence within creation in the sacramental forms of its worship. There the humble realities of our world become icons of the mystery at work. From beginning to end, and in each conscious moment, the Christian universe is one of ever-original gift, of self-giving relationality, and of ongoing transformation.

Thus, the basic mysteries and essential energies of Christian faith offer deep resources in the building of a sense of global community within a hopeful universe. As such faith learns from the explorations of science and from the moral force of the global concerns now stirring in human history, it is enabled to communicate new perceptions of shared meaning and common good. As it discovers the riches of other religious faiths and traditions, Christian faith finds itself in a situation for which its central mysteries have been preparing it, and out of which it can contribute powerfully to a gracious sense of shared existence.

If ecology in its Greek roots signifies ‘the meaning of the home', Christian faith can find a new home-coming in entering into such awareness and concerns. The awareness of such a homecoming, not as an alien intruder but as a member of the family, is now a significant emphasis in current theology.[20]

7. The Humble Self

In many ways, to bring faith, ecology and cosmology together is a move to put our souls back into our bodies. Culturally speaking, we human beings have become a disembodied race, sorry victims of our narrow success. The last few centuries have seen us trying to organise life and our world in a kind of weird objectification of ourselves, impervious alike to the wisdom of nature and the wisdom of the spirit. The result is that we now groan under a huge carapace, a heartless impersonal superstructure of economic and social order that has lost its human scale. We have become unselved and denatured.

It is almost as though we have lived through the extinction of humility, understood as our native earthliness. To the humble of heart is given a sense of the human scale: we are not the centre of the universe; that lies beyond us. We are not pure spirits, for we are intimately related to the earth itself, in our origins and in our end. As humanity lost humility, it interiorised a grotesquely truncated and distorted sense of the human self.[21] This denatured self-image tended to turn the human person into an isolated little ghost, more or less haunting the world, and no longer incorporated into the one body of creation. The huge machine of modern technology has not only uprooted us from nature, but cut us off from one another. ‘Upward mobility' has been a strange journey. For ‘upwardness' has become up-rootededness, from the earth itself, from the biosphere in which we exist, and from the mysterious ground of existence itself. We have become, to use Walker Percy's phrase, ‘lost in the cosmos'. [22]

Certainly, the holistic mentality of our day is contesting the shrinking of the self to such tiny individualistic and disembodied proportions. But the absorption of a general mentality will not be enough. Unless we confront the deep dis-ease of our culture and thoroughly diagnose it, we are exposed to the danger of infecting our new-won ecological concerns with what is still profoundly unhealthy. On the other hand, we may be so vividly aware of the diseased state of affairs, that we start to recoil from what we have become, and give way to disgust. At such an extreme, ecological awareness begins to include within it a kind of self-hatred, a disowning of the human, to end in a generalised misanthropy. Out of such self-disgust, we begin to project onto an increasingly abstract nature what is most unexamined and unredeemed in our own selves.

As faith seeks a new connectedness with the earth and the cosmos itself, it promotes the conversion of self-consciousness to a more authentic standard: the currency of inner capitalism has to be exchanged for real values. The realisation that ‘we are up to our necks in debt' to the world of nature,[23] tempts us to file for bankruptcy, or to leave the country before the debtors find us. But where can we hide? Therein lies the human problem.

Just as despair is fundamentally a failure of imagination, true hope is formed out of the active imagination of those who have the humility to recognise this earth as the shared body of our existence. Imagination regains its courage when it is prepared to diagnose the harm caused by the refusal of our earthly status. Our creativities are newly inspired to the degree we are disposed to yield ourselves into a more intimate collaboration with the gracious mystery of Life, however it has been revealed to us.

8. The Inclusive Language of Faith

The reshaping of theology along new lines is an immense task. Fortunately, it has already begun; and in such beginnings, despite the inevitably complex developments that are taking place, two points of radical simplicity are worth stressing: first, the search for a language of universal inclusiveness; and secondly, the extension of the meaning of the greatest of all commandments.

In forging a theological language that will be inclusive of disowned or hitherto unknown dimensions of existence, we need to focus on the fundamental story of creation, as ‘the whole story', in a way that invites all the dramatis personae to claim that story as their own. Admittedly, the issue of inclusive language has been mainly restricted to a feminist criticism of the religious, political and social metaphors that have structured a patriarchal system in the past, and still marginalise women's experience in the present. The Christian story must look to a new telling point at which a positive valuation of the feminine will be assured. The points usually emphasised are the original creation story of Genesis, the Wisdom tradition, Jesus' own inclusive dealings with women, through to Paul's vision of humanity made one in Christ.

But the feminist inclusiveness does not stop here. As most critical feminists assure us, their critique is a prelude to a far vaster form of theological inclusiveness,[24] one that respects the whole world of our relationships, not only to one another and to God, but to the biosphere, the planet, the cosmos itself. We are looking for an inclusive language to enable a communication of the cosmic dimensions of the Christology of the Johannine tradition and of the later Pauline epistles. If all things are made in Christ and through him, if he is the origin, coherence and goal of the entire universe of God's creation (Col 1:16-19), then ‘all things' have to be given their due in a genuine Christian vision.

In the present context, the original story now demands a telling in a situation vastly different from that of the biblical authors. The all-inclusiveness of the creation story and the Christian Gospel now have to integrate realities inaccessible to the imagination of former times. Such realities extend from the infinitesimal interactions of tiniest sub-atomic particles to the outermost exploding star in the furthest known nebula billions of light years away; they include the helical dance of the DNA and the complex ecologies of the rain forest; the disconcerting world of quantum mechanics, radiation from the Big Bang and impenetrabilities of black holes and dark matter.

Whatever the complexity involved in all this, the challenge to faith can be expressed in terms of simple questions: how does our emerging sense of human integrity and relationship demand a new telling of the whole story? How do we pass from the limitations, preoccupations, and even the perversions of unwarranted exclusiveness, to a more thorough-going inclusiveness, one more open to the whole realm of human experience, more worthy of the implicit universality of the faith we profess? It comes down to this: How do we all belong, including the pre-personal, in the one mystery of the universe? Reflecting on the inclusiveness of that ‘we' is a good way of introducing a range of larger questions.

The earlier theology of this century was largely concerned with the mystery of the human person under the threat of violent, totalitarian ideologies. In reaction to the philosophical abstractness of past thinking on human nature, the emphasis was laid on the concreteness and irreplaceable uniqueness of each human person. To this degree, theology became preeminently a theology of the ‘I'.

More recently, such a concern has been revealed as all but romantic unless attention is paid to the structures that shape human life: social, economic, political, cultural. You could say theology turned critically to the reality of the transpersonal ‘It' of the human world, the socio-political and economic structures that have proved so deeply inimical to the transcendent value of the human person. By concentrating on that ‘It', following the lead of the social sciences, theology implicitly invited the ‘I' to understand and declare itself in terms of a socially and culturally formed ‘We'. And this led to another range of questions: with whom are you in solidarity? Who do you stand with? Who do you speak for?

Here the various versions of the option for the poor, of solidarity with victims, of a history seen ‘from the underside' were worked out. And often they achieved noble expression, as when the blank cheques of such phrases were cashed in terms of heroic resistance and even of martyrs' deaths in the various proponents of Liberation Theology. Out of that experience and commitment, Christian reflection is entering into the expression of an even larger ‘I', of a far vaster and interconnected ‘It', of a ‘We' realised in an immense inclusive communion.

The key contexts now are ecological and cosmic. The ‘I' is invited into an awareness of its embodiment in the interconnected, multiform life of the planet itself. The human person is newly perceived as an ‘earthling' in the great temporal and spatial genesis of the cosmos itself. The growing appreciation of such an ‘It', the planetary web of life and the cosmic process that has given birth to it, inspires a fresh expansion of the ‘We'.

For it is a ‘We' born out of humility, responsibility and hope. Out of humility, for it arises from our inescapable dependence on a world of living and non-living things for our existence, nourishment and delight. Out of responsibility, because human freedom at this point of history is radically shaping, for better or worse, the whole world of ecological existence. The fate of the planet and of future generations of living things and persons has come to depend on human decisions. Out of hope, too, since faith lives from its conviction that we are not alone in the universe: there is an ‘Other', creatively, graciously present in every moment. . .

The great Barbara Ward, writing decades ago, captured the simplicity we refer to here:

When we confront the ethical and natural context of our daily living, are we not brought back to what is absolutely basic in our religious faith? On the one hand, we are faced with the stewardship of this beautiful, subtle, incredibly delicate, fragile planet. On the other, we confront the destiny of our fellow man, our brothers. How can we say that we are followers of Christ if this dual responsibility does not seem to us the essence and heart of our religion?[25]

9. The Great Commandment and a Holistic Response

This leads to the second point of radical simplicity as it expressed in the twelfth chapter of Mark's Gospel. Asked, in accord with a well-known practice, which is the greatest of the 613 commandments of the Law, Jesus makes the following reply:

The first is, ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, The Lord is one; you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.' The second is this, ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself.' There is no other commandment greater than these. (Mk 12: 29-31)

The whole cosmic and historical focus of Judaeo-Christian experience is on the supreme value of worshiping the One God. That uniqueness demands an unreserved and total response. It calls forth an unconditional integrity on the part of the believer. Heart and soul, mind and strength evoke all the dimensions of that integrity – a ‘holism' that leaves nothing out. It is a matter of responding with all that we are, in every dimension of existence. It would probably be forcing the original meaning of this biblical text to make too much of the distinction of the four terms employed to evoke the totality of the desired response. Still, a certain amount of imaginative translation might be permitted in order to sensitise us to the force of this great summons in the present search for a larger integrity and inclusiveness.

We might suggest, then, that ‘with all your heart (kardia)' implies something like the prophet's ‘heart of flesh' replacing the ‘heart of stone' (Ezek 36:28). What is at stake is a new capacity to feel, with a new affectivity and compassion. It is looking to a larger integration of the ‘all' into capacities of the human heart. It demands that we begin to have a heart open to the crisis in which our ‘beautiful, subtle, incredibly delicate and fragile planet' is involved. Hence, the great commandment is meant to be a heart-felt appeal. As such it bears on the conversion of feeling; and of turning hitherto unfocussed feeling into creative passion for the integrity of God's creation. Without that deepening and broadening of feeling to include all creation, a the heart would not be whole, but be numbed in its service of God.

Then, ‘ … with all your soul' (psyche). This dimension of existence usually implies, in the many strands of biblical, theological and philosophical tradition, the human life-principle. Without such a soul, the body is dead. Because of the eminence of human life in the world of creation, the soul has often been understood as that which distinguishes and separates the human from the inanimate, and from other, lesser forms of creation. And because it is the spiritual aspect of human existence enabling human beings to relate directly to God, it is that which has to be ‘saved', to be plucked out of the chaos of the world at all costs. Obeying the great commandment in the present context demands a revised understanding of the soul, if we are to love the ‘Lord and giver of life' with a new wholeness. The ecological and cosmic context of our embodiment suggests that the soul is that which vitalises the human being in an animated communion with all living things. It is the principle of radical connection to all reality. As Greek philosophers and medieval theologians stressed, anima est quoddamodo omnia – ‘the soul is in some measure all things', a principle of openness to the universe. Because a human being has a soul, he or she lives not merely in an animal habitat, but in a universe of communication in meaning and in mystery. The soul is the root of our capacities to celebrate and transform the world. Hence, loving God with one's ‘whole soul' is, in a profound sense, offering to God life conscious of itself as a gift, life exulting in the mystery of communion, life in contact with a universe. The soul is not a spiritual escape route from an indifferent or sinful creation into a divine realm, but our human capacity to accompany creation in its journey to God, with the energies of love, thanksgiving and wisdom.

In a similar vein, loving God with ‘all your mind' (dianoia), means loving God with a mind made whole by reflecting on the Whole. It is a mind dedicated to an inclusive understanding, as it explores and celebrates the wondrous diversity and beauty of all creation. It is a wholeness won by dint of disciplined openness to the new, by patient learning, through loving familiarity with everything as a manifestation of God's creative presence; and in humility before the mystery of it all. It is mind turned contemplative as it beholds creation as the temple of God and as the manifestation of divine glory. More practically, for Christian faith, it is mind ready to relearn its basic meanings of God, incarnation, hope and moral life in the light of the new sciences of wholeness.

Finally, ‘with all your strength' (‘ischus) comes to have the meaning of using the best energies of the heart, the soul, the mind in the service of the Creator; and in collaborating with the divine in our service of creation. The strength, the energy, the enterprise that characterise human history have all too often been intent on self-promotion, directed to the domination of others. Now, the integrity of human strength is called to manifest itself in other-regarding service, in making connections, in promoting communion, in hallowing rather than desecrating the earth as the shared body of our co-existence. In loving God with the resources of such strength means offering to the Creator a personal contribution for the sake of the ‘all', the whole, the Reign of God in which all creation will come into its own.

The link that I have been making between the integrity of our self-offering to God with the inclusiveness of our relationship to all creation is supported in the way Jesus links this great commandment to be wholly centred on God with a second commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself'. The implication is that we can only come to the one God in the company of the neighbour. Relationship to the other is inherent in relationship to oneself. One's ‘self' in the world of God's creation is essentially relational, a self with and for others. Loving God means living in a limitless open circle of often disconcerting inclusion. We cannot imagine we love God because we love no one in particular. This love of the created other, our neighbour, has now to develop into a new sense of communion and companionship with the whole of this creation. It has to mean not only care for the suffering human neighbour, but also care for all forms of life, and for all the life-nourishing elements and conditions that have so often been taken for granted in the ungracious culture of our times. Needless to say, neglect or exploitation of these larger, pre-personal dimensions of the ‘other' has been to the detriment of our human neighbour, present and future. We can no longer imagine we love our neighbour without having a care for the neighbourhood.

In the light of this contextual appropriation of the great classical commandments of Judaeo-Christian tradition, God is not just the ultimate focus of an individual soul, but the space of mystery in which all the cosmic and ecological ‘We' and ‘It' come to be. The whole of the human heart and soul and mind and strength – all our capacities to relate, to pray, to imagine and to think, to make and to create – are invited to expand into infinities of Love. That is the mystery from which the universe emerges, the atmosphere it breathes, the source of its ultimate transformation. Perhaps we can begin to read S. T. Coleridge's words at the end of ‘The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner' in a new light:

He prayeth best who lovest best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God that loveth us,

He made and loveth all.10. From Simplicity to Complexity

We turn now from simplicity of a new inclusive language and of a more generous universality in our love of God and neighbour, to the complexity involved in articulating and implementing such wholeness. For the development of a Christian theology adequate to the task, an immense, long term collaboration is required. In the meantime, the present situation is extremely complex; and even chaotic – in the (now) good and bad senses of the word. The early phases of the current situation were marked by bitter recrimination on all sides. You could sense an extreme irritability which is perhaps characteristic of cultures that have become so complex that any common meanings and values are increasingly elusive. The variety of complaints is well known. For instance, some are determined to dismiss the Judaeo-Christian tradition as inimical to ecological awareness and scientific versions of the cosmos. Religious faith is understood by them as necessarily demeaning the natural in its concern for an other-worldly transcendence, as though the world is simply the prelude to a post-mortem spiritual fulfilment. Others reject science itself as a kind of learned stupidity that has lost itself in the parts of reality it explores, to the forgetfulness of the whole. Bacon, Newton and Descartes are the main villains in this scenario of recrimination. Others reject technology as alien artificiality interfering with pristine nature; while others reject the West, or the North, as imposing oppressive economic structuring on the East or the South. Others single out Capitalism or industrialism or modernity, or post-modernity as the culprit. Then, too, powerful feminist voices among the ecologically minded proclaim the culprits as patriarchy, hierarchy, chauvinism – male domination in all its forms. The most disconcerting rejection is that of humanity itself as some kind of selfish pest infesting the planet and perverting the happy ordering of the natural world.

Of course, as all these huge groups are singled out for their destructive influence in the present situation, they have defended themselves of criminality, and found ‘Greenies' at best romantic dreamers, or, at worst, New Age fascists willing to sacrifice everything to their aims. There is no point in pretending that such antagonisms were not, and are not, partially justified. Yet they are not the whole story, and cannot be if there is to be any possibility of more enlightened collaboration. Hence we must hope that the situation can rapidly move into a constructive, collaborative phase as Christians and other religious believers, as scientists and industrialists of the North and the West, begin to own the common crisis; as critical feminists continue to explore the full extent of our common problems; and as ecological activists realise that they are not alone in their concerns.

Christians have to repent of their sins; and it might be no small service to give the lead here. Each one of ‘the seven deadly sins' has an anti-ecological connotation to it: pride (the rejection of the humility of the human scale); covetousness (defining oneself in terms of having, rather than being); lust (the denial of the sacredness of life and relationship); anger (the extreme intolerance that sees all diversity as a threat); gluttony (the destructive consumption of precious common resources); envy (a self-absorption that permits no gratitude, or joy in the diversity of gifts); and sloth (expecting nature and life to give us a free ride)! There can be no real collaboration without acknowledging failure, powerlessness; and asking forgiveness for falling short of the great commandments of love, and for failing to live out the whole logic of the incarnation of God amongst us. Still, I think Christian life, in the essential energies of its faith, hope and love, has more to offer than the seven deadly sins of Christian failures. Grace keeps on being grace; and the healing and hope it offers can be a beneficent influence in the great concerns of the moment.

Moreover, I think we should bear in mind that the last two hundred years, so destructive of biosphere, have been notably unfriendly to Christianity as well. Scapegoating either Christianity or science, or technology or humanism, or men, or the North or the West, while it might be understandable given the widespread panic and desperation many feel, tends to obscure both the gravity of the problem and the possibility of any solution. Nothing is quite as simple as our first apprehensions of a problem incline us to think, especially when we realise, despite the advances of scientific knowledge and ethical commitment, how little we really know. Focusing on single issues does not readily lead to inclusive thinking.

Every attempt to enter into the ecological conversation faces us, whatever our point of view, with the deepest kind of philosophical questions. Amongst these, the most important turn on the meaning of nature in general, and of human nature in particular. That, in turn, leads to the necessity of exploring the relationship between nature and human history, and between both these and the cosmos as a whole. If such explorations bring us back to ourselves as the shapers of the future in some decisive way, we soon find ourselves pondering on the criteria for ethical decision and the role of human intelligence as a directive force in the evolutionary process: how are we all caught up in a common cosmic purpose? Huge questions move and shift below the surface of any conversation.

In the midst of such complexity, the wisest stance is to begin where we are and to see what we can do. As Merry, the Hobbit in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, advised, ‘It is best to love what you are suited to love, I suppose: you must start some place, and have some roots, and the soil of the Shire is deep'.[26] What is at stake at every point is a more expansive and inclusive love. The love our neighbour has now to include so much else as we awaken to the mysterious universe of our co-existence, and the varied forms of life it has brought forth. The love of our God, too, must expand in gratitude and in a larger, more generous collaboration with the divine will that has brought us into existence, that has brought us together on this earth, that has made each of us a necessary presence in the destiny of the other: ‘it is best to love what you are suited to love…'.

‘You must start some place'. In the long, demanding movement into a new phase of history, it is to be expected we will have different starting points. Democracy and pluralism are resources, not limitations. What matters is that each of us seeks to rejoin the human race, enter the stream of life, from where we are, in a new celebration of life's manifold mystery. History invites, whatever our distinctive paths and pace, that we move together in the one direction. It counsels, too, a greater reserve in excommunicating one another from the planetary community we now are. For we have at least two things in common: the common body of our earth, and the future that is coming upon us. Like it or not, we are fellow travellers, and we have to make the best of it. The realisation is dawning that we can no longer be passengers in the ark more or less discomforted by the odd variety of other living things that bark or howl or sing or hiss or roar and growl in other compartments of boat. All share the same crisis. It is up to the human family to determine the direction and reach landfall before it is too late. Without that shared sense of direction, every wind is contrary, and we remain adrift in a world of growing troubles.

My own starting point, shared, one way or another, by at least a quarter of the world's population, is Christian faith. ‘You have to start some place, and have some roots': the roots that I will be emphasising are the perennial roots of Christian faith: the self-giving communion that is the trinitarian God; the universe as God's creation; the incarnation as the genesis of God within that creation; the sacramental nature of all reality; human consciousness become conscience in responsibility to the Other and the Whole... These are roots are deep indeed; and in these times of crisis, it would be a failure of cosmic proportions for Christians to let these roots wither.

‘And the soil of the shire is deep': Merry might forgive us for extending his much loved shire to mean the whole of our beautiful planet. Here, in this place, we are feeling the need to earth ourselves again, to recover our identity, not as Hobbits, but as earthlings, humbly and lovingly connected with all life in the ‘meaning of our home' (the logos of the oikos). The soil, the humus is deep; the deeper we go into the soil of the life and existence we share, the greater communion we will enjoy in moving toward a more gracious, a more ‘humble' existence together. For Christians that depth is especially revealed in the entry of God into our world, and indeed, into all the dimensions of our existence.

11. The Vocabulary of Roots and Connections

The scope of a repentant and reconciling Christian holism can be helpfully traced by dwelling in the roots of three key words: ecology, religion, and catholicity.

First, `ecology'. This word has been in use little more than a century after being coined by the German zoologist Ernst Häckel. Its Greek roots imply, ‘the meaning of the home', as we have just mentioned.[27] Consequently, it came to refer to the study of the complex totality of conditions necessary for the survival of particular living organisms. By stressing the complexity of relationships characteristic of a given organism, it not only emphasises the importance of such ‘co-existence', but also raises the question of the extent to which living things are fundamentally living relationships. The exploration of such interconnectedness throws light on how living things, whatever their species, are truly at home in earth. As a new science of wholeness, it explores the ‘home', the oikos, as the matrix of all the relationships of living beings, where each living thing is at home and has a livelihood.

In highlighting the interconnectedness of everything in the one web of life of planetary life, ecology soberly warns us that ‘everything goes somewhere', not only to nourish but also to pollute a larger world. Thus, ecology is concerned to explore nature ‘in the round', so to speak, in all the intricate, delicate interactions that characterise life on this planet. It is the study of our planet as a community of communities where a species is not just an isolated specimen, but a facet of living, interconnected totality.[28]

The second key word is religion. This time the Latin roots are instructive: religare (to bind together again) or re-eligere (to renew one's choice). A fresh comprehensiveness of faith and action is implied. The religion of this time must aim to tie our experience together in a greater wholeness, and to choose the path of wholeness for a shared healing and a common health. A deeper, more tender relationship of deliberate bonding to the earth and the universal process will tend to make us see life, not as a bundle of problems to be solved, but first of all, as a gift, a shared connectedness within a life-giving mystery. The problem in recent centuries has been that our religious sense has not notably linked us back to the earth, nor linked us in with the whole communion of living things. This is an odd attenuation of Christian experience. For, with its accent on creation, the incarnation of the Word, the resurrection of the body, the sacramental character of the divine presence, Christian faith is, in so many ways, the most earthy and material of all religions .

Our third word, there is catholic, from the Greek kat' holou, literally, ‘universal', ‘all-embracing', ‘in accord with the whole'. It has, of course, its original historical meaning in the self-description of the Catholic Church, in its institutional intent to welcome the whole – the totality of God's revelation and the totality of Christian response in all the variety of cultures and languages in which it occurs. But whatever our particular Christian traditions – Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican, Protestant – catholicity is generally accepted as a mark of the authenticity of faith. It remains, therefore, a mark of fundamental Christian concern; but now as awaiting a larger application in an ecological and cosmic frame of reference. Such catholicity evokes a more expansive way of indwelling creation as participants in the totality of the mystery revealed there, in the one mystery of Christ ‘in whom all things hold together' (Col 1:17). Here Simone Weil's question is pertinent, ‘How can Christianity call itself Catholic if the universe is left out?'[29]

This cursory reference to the classical derivations of these key words suggests a far more serious search for roots. How might the sense of the living planetary whole extend the wholeness that Catholic faith pretends to celebrate? How is the whole marvellous web of life on this planet to be integrated into the Catholic sense of ‘grace healing, perfecting and elevating nature', in a way that makes connections with the Catholic doctrines of creation, Trinity, incarnation, sacrament, and natural law? How, in short, in the face of the eco-catastrophe that threatens planet earth today, might a Catholic sense of the universe welcome and promote a more profound ecological commitment?

12. Conclusion to the First Circle of Connections

One can hardly doubt that some enormous change is called for in human culture, in our particular life-styles, in the expression and practice of our faith. There is an anxiety inherent in the ‘turning point' we have been considering. Will it really become a turn-about, a conversion of the religious, moral, intellectual and spiritual dimensions that are necessary?

The concluding lines of E. F. Schumacher's Guide to the Perplexed seem to me to offer salutary advice:

Can we rely on it that a ‘turning around' will be accomplished by enough people quickly enough to save the modern world? This question is often asked, but no matter what the answer, it will mislead. The answer ‘Yes' would lead to complacency, the answer ‘No' to despair. It is desirable to leave these perplexities behind and to get down to work.[30]

In that spirit, we will continue with this search for connections, as a tiny ingredient in the great conversation on the meaning of life and of our place in it. Each of us has to enter the conversation from where we are. The more we own that standpoint with humility (conscious of its limitation), with hope (we are not alone in the universe), with compassion (we are all involved together in the great drama of life), with imagination (we are stirring to the intimations of a new dream), the more genuinely ecological the conversation will be. It is a matter of meaning our lives as an ever-expanding, open circle.

We must now enter into the second circle of connections.

[1]. See N. M. Wildiers, The Theologian and his Universe. Theology and Cosmology from the Middle Ages to the Present (New York: Seabury, 1982). The ‘his' in the title of this excellent book unwittingly substantiates the author's thesis!

[2]. See Vatican 1, Constitution on Divine Revelation: human intelligence illumined by faith reaches some understanding of its mysteries `by analogy with truths its knows naturally, and also from the interconnection of the mysteries with one another and in reference to the ultimate human destiny'.

[3]. For a good expression of the challenge, see John Honner, ‘A New Ontology: Incarnation, Eucharist, Resurrection, and Physics', Pacifica 4/1, February 1991, pp. 15-50.

[4]. Of special value here is Juan Luis Segundo's monumental work, Jesus of Nazareth Yesterday and Today, I-V, trans. John Drury (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1984-88). For an impressive overview, see Frances Stefano, ‘The Evolutionary Categories of Juan Luis Segundo's Theology of Grace', Horizons 19/1, Spring, 1992, 7-30.

[5]. ‘Echoes of the Big Bang', Time Magazine, May 4, 1992, pp. 50f.

[6]. See for example, Ian Bradley, God is Green. Christianity and the Environment (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1990); and Rupert Sheldrake, The Rebirth of Nature. The Greening of Science and God (New York: Bantam Books, 1992).

[7]. As regards the Earth Summit conference itself, it is true that the 8,000 journalists present did not give it a good press. Still, this unique meeting did bring together 40,000 participants from 178 countries, including 116 heads of state. Further, the Rio Declaration of 27 principles and the 860 page Agenda 21, and two legally binding conventions on biodiversity and climate change remain as guidelines for the next decade. A sustainable Development Commission has been set up to monitor the implementation new ecological programs. See Keith O'Neil, The ‘Road from Rio', Justice Trends 66, September 1992, p.3.

[8]. De Anima, 111,8.

[9]. Niels Bohr, for instance: ‘If anybody says he can think about quantum physics without getting giddy, that only shows he has not understood the first thing about them'. For this and similar remarks by Richard Feynman, Albert Einstein and Wofgang Pauli, see Christopher F. Mooney, ‘Theology and Science: A New Commitment to Dialogue', Theological Studies 52/2, June 1992, 398- 405.

[10] . On the subject of the imagination and hope see the modern classic, William Lynch, SJ, Images of Hope. Hope as the Healer of the Imagination (Notre Dame, Indiania: University of Notre Dame Press, 1974).

[11]. Murray Bookchin, Philosophy of Social Ecology. Essays in Dialectical Naturalism, p. 10.

[12]. Bernard Lonergan, Method in Theology (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1971) pp. 107; 115.

[13]. Dag Hammarskjöld, Markings, trans., W.H. Auden and Leif Sjöberg (London: Faber and Faber, London, 1964) 169.

[14]. For the full import of such a phrase, see David Tracy, The Analogical Imagination. Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism (New York: Crossroad, 1981).

[15]. The list of outstanding contributors would be very long, and my own assessments will be clear from the documentation I offer in the various sections. These will range all the way from the great ‘paradigm shifters' such as Teilhard de Chardin, Bernard Lonergan and Karl Rahner, to such gifted communicators as Thomas Berry, David Toolan, Sean McDonagh, and Denis Edwards, right through to vigorous popularisers such as Matthew Fox. I acknowledge, however, a special debt to those who bring the complexities of science and the sense of faith together in their distinctive ways – writers such as Charles Birch, John Honner, John Polkinghorne, Arthur Peacocke, Stanley Jaki, Ian Barbour, and Christopher Mooney.

[16]. J. Ronald Engel, ‘The Ethics of Sustainable Development', in Ethics of Environment and Development, I. Robert Engel and Joan Gibb Engel, Eds. (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1989) 13-15. Also James A. Nash, Loving Nature. Ecological Integrity and Christian Responsibility (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1991) is especially valuable in the section ‘The Ecological Complaint against Christianity', 68-91.

[17]. In reference to the deep structures conditioning management theory, see Jeremiah J. Sullivan, `Human Nature, Organisations and Management Theory', Academy of Management Review 11/3, 1986, 534-349.

[18]. Here the towering figure in the theology of beauty is Hans Urs von Balthasar.

[19].See Ethics of Environment and Development, I. Robert Engel and Joan Gibb Engel, Eds. (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1989) for an excellent example of the current dialogue.

[20] . For a valuable survey of authoritative statements and theological resources, see Denis Edwards, ‘The Integrity of Creation: Catholic Social Teaching for an Ecological Age', Pacifica 5 (1992), 182-203.

[21]. For a challenging treatment of this theme, William Barrett, Death of the Soul. From Descartes to the Computer (New York: Doubleday, 1986).

[22]. Walker Percy, Lost in the Cosmos. The Last Self Help Book (London: Arena, 1983).

[23]. David Toolan, ‘”Nature is a Heraclitean Fire”. Reflections on Cosmology in an

Ecological Age', Studies in the Spirituality of the Jesuits 23/5 November 1991 [whole issue].

[24]. See Anne Primavesi, From Apocalypse to Genesis. Ecology, Feminism and Christianity (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991).

[25]. Barbara Ward, ‘Justice in a Human Environment', IDOC International 53 (May 1973) p. 36.

[26]. J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Vol. 3 (New York: Ballantine, 1965) 179

[27]. Douglas M. Meeks, God the Economist. The Doctrine of God and the Political Economy (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989) 33-35.

[28]. For an interesting attempt to set new perceptions into a larger tradition of philosophy, see Laura Landen, ‘A Thomistic Look at the Gaia Hypothesis: How New Is This New Look At Life?', The Thomist 56/1, January 1992, 1-18.

[29] . Simone Weil, Waiting for God (London: Fontana, 1959) p.116.

[30]. E. F. Schumacher, A Guide for the Perplexed (New York: Harper & Row,1977) pp. 139-140.