Cremorne Theatre (Brisbane)

Situated on the South Bank of the Brisbane River near the Victoria Bridge, the Cremorne Theatre at South Brisbane was originally an open air venue; a constant dilemma for Edward Branscombe was what to do with his audience if it unexpectedly rained during a performance and how to encourage people not to stay away at the first sign of rain. Advertisements reminded people that “entertainments are given in wet or fine weather, as the theatre is protected by waterproof coverings” (Brisbane Courier 4 Feb. 1914: 6). When the weather was fine, the audience enjoyed the riverside breezes offered by the Cremorne. “The weather just now is ideal for open-air entertainments, and the general excellence of the programmes makes their popularity the greater” (Brisbane Courier 21 Mar. 1914: 12). Preparations, however, were being made for rainy days and at the end of the month their success was recorded:

Big extensions have recently been made to the already large waterproof awning at Cremorne, the home of the Dandies, and the curtain now covers about three quarters of the whole area of ground. The result was that when the rain poured down on Saturday night patrons were able to listen to a bright entertainment in every degree of comfort. (Brisbane Courier 30 Mar. 1914: 8)

These extensions also included the installation of a gallery which increased the capacity of the building (Brisbane Courier 9 Mar. 1914: 12).

When the Cremorne opened in August 1911, it was 88ft by 165ft and had a seating capacity of 1800. The stage dimensions were 52ft long and 22ft deep and there was a central opening to the stage measuring 36ft by 12ft (Brisbane Courier 5 Aug. 1911: 6). There was a ceiling above the stage area which was “lit by electric lights of 3000 candle power” (Brisbane Courier 5 Aug. 1911: 6). The ground of the auditorium was covered in bark and seats were arranged in a semi-circle around the stage.

A.E.

Appleton equipped the Cremorne and John N. McCallum acted as general manager

for Messrs. Branscombe Ltd., the proprietors of the theatre. According to

Bill Clayfield and Les Tod “it was little more than a huge timber and iron

barn, but what it lacked in terms of theatrical decoration, it more than made

up for in theatrical soul” (Clayfield 20). Despite the advertised claims

that patrons would remain perfectly dry, every year before the Dandies opened

their new show at the Cremorne, Edward Branscombe organised for renovations

to be undertaken in an attempt to help the theatre better stand up to Brisbane’s

summer rain. “Cremorne has undergone the usual spring cleaning, and has been

fitted with perfectly waterproof awnings and side screens by which means the

popular open air theatre has been converted into a large canvas hall affording

protection not only from rain, but from wind and cold” (Brisbane Courier

7 Aug. 1916: 11). At this time John N. McCallum, installed a large gutter

which was designed to drain all the water from the overhead awnings, “thus

keeping the floor perfectly dry” (Brisbane Courier 23 Sep. 1916: 12).

The new stage included “strikingly handsome” black velvet curtains. “With

such excellent surroundings the company of 12 artists are perfectly happy,

and they appear to enjoy the entertainment as much as the audience” (Brisbane

Courier 23 Sep. 1916: 12). The description of this open-air venue as

“warm and cosy” became a journalistic cliché with the canvas covering being

mentioned in ‘reviews’ every time there was a sign of rain:

A.E.

Appleton equipped the Cremorne and John N. McCallum acted as general manager

for Messrs. Branscombe Ltd., the proprietors of the theatre. According to

Bill Clayfield and Les Tod “it was little more than a huge timber and iron

barn, but what it lacked in terms of theatrical decoration, it more than made

up for in theatrical soul” (Clayfield 20). Despite the advertised claims

that patrons would remain perfectly dry, every year before the Dandies opened

their new show at the Cremorne, Edward Branscombe organised for renovations

to be undertaken in an attempt to help the theatre better stand up to Brisbane’s

summer rain. “Cremorne has undergone the usual spring cleaning, and has been

fitted with perfectly waterproof awnings and side screens by which means the

popular open air theatre has been converted into a large canvas hall affording

protection not only from rain, but from wind and cold” (Brisbane Courier

7 Aug. 1916: 11). At this time John N. McCallum, installed a large gutter

which was designed to drain all the water from the overhead awnings, “thus

keeping the floor perfectly dry” (Brisbane Courier 23 Sep. 1916: 12).

The new stage included “strikingly handsome” black velvet curtains. “With

such excellent surroundings the company of 12 artists are perfectly happy,

and they appear to enjoy the entertainment as much as the audience” (Brisbane

Courier 23 Sep. 1916: 12). The description of this open-air venue as

“warm and cosy” became a journalistic cliché with the canvas covering being

mentioned in ‘reviews’ every time there was a sign of rain:

Open-air entertainments are delightful on summer evenings in Brisbane, and the popular “Cremorne” theatre, situated on the river back, South Brisbane, facing the south-east, and open to the cool breezes, is always a favourite resort. During the cool evenings, and when the weather is threatening or unpropitious, the popular theatre is converted into a huge canvas hall, and completely enclosed in waterproof awnings and side screens which afford protection against inclement weather. The main head covering is composed of best waterproof tarpaulin, and the water is caught in large gutterings, and carried through special drains direct into the Brisbane River. The sides are fitted with canvas screens reaching to the ground, thus preventing the rain from beating in, and affording complete protection from the wind. Agricultural drains in the auditorium render it impossible for moisture to affect the floor of the theatre. “Cremorne,” therefore, is perfectly warm, snug, and cosy, and when one witnesses the excellent entertainment provided by Mr. John N. McCallum’s “Courtiers,” it is not surprising that large audiences assemble there nightly. (Brisbane Courier 22 Sep. 1917: 12)

One of the performers at the Cremorne, Dulcie Scott, described the makeshift roof in less flattering terms; the frequent claims made in the advertisement did not match her recollection of the building. The ‘roof’ was “a canvas awning overhead that operated on ropes. At least, the canvas was supposed to operate on the ropes when it rained, but half the time it wouldn’t work, and when it did, the canvas quickly filled with the rain and soon was pouring just as heavily through the canvas as it would have unimpeded” (Truth 28 Feb. 1954: 15). Under McCallum’s proprietorship the theatre eventually gained a proper roof (Donovan 42).

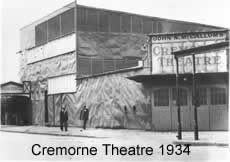

In

1934 the Cremorne like many live theatres was wired for sound. The Cremorne

was leased to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for 2 years from 1934 to 1936 and this seems

emblematic of the domination of the talking film over live performance. George

Rae was the architect for the new-look theatre. He halved the width of the

auditorium by adding false walls in an attempt to make the space suitable

for film (Clayfield 23). This reduced the seating capacity of the theatre

to 1300 but also effectively improved the acoustics and the ventilation (Clayfield

23). When MGM’s second lease expired in January 1940, the Roxy Theatres from

Sydney managed the space and continued to present films (Courier-Mail

15 May 1940: 9). Vaudeville took the stage at the Cremorne in 1940 and thus

survived this temporary invasion of the cinema and managed to dominate the

professional theatre scene in Brisbane for another decade. Harry O. Wren

from Wren’s Greater Theatres Pty. Ltd. organised for the theatre to be rebuilt

and John N. McCallum became the lessor of the theatre.

In

1934 the Cremorne like many live theatres was wired for sound. The Cremorne

was leased to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for 2 years from 1934 to 1936 and this seems

emblematic of the domination of the talking film over live performance. George

Rae was the architect for the new-look theatre. He halved the width of the

auditorium by adding false walls in an attempt to make the space suitable

for film (Clayfield 23). This reduced the seating capacity of the theatre

to 1300 but also effectively improved the acoustics and the ventilation (Clayfield

23). When MGM’s second lease expired in January 1940, the Roxy Theatres from

Sydney managed the space and continued to present films (Courier-Mail

15 May 1940: 9). Vaudeville took the stage at the Cremorne in 1940 and thus

survived this temporary invasion of the cinema and managed to dominate the

professional theatre scene in Brisbane for another decade. Harry O. Wren

from Wren’s Greater Theatres Pty. Ltd. organised for the theatre to be rebuilt

and John N. McCallum became the lessor of the theatre.

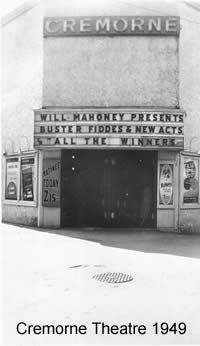

The popular appeal of vaudeville declined after World War II and the Cremorne closed its doors. Ceasing to operate as a vaudeville venue in 1949, the space was used by amateur groups such as the Musical and Theatre Guild of Queensland (Donovan 73). After 40 years of proprietorship, John McCallum sold the Cremorne to Universal-International Pictures (Courier-Mail 10 Dec. 1951). The space was converted into the offices of a major film distributor in 1952, once again a symbol of the increasing dominance of film (Courier-Mail 11 Oct. 1975/Western Advertiser 4 Feb. 1982). When the theatre was destroyed by fire on 18 February 1954, the cause was “the combustion of the inflammable film” (Kursey, JOL, OM79.002/1). The night of the fire was an emotional time for many Brisbane theatregoers. An estimated 40,000 Brisbane residents stood and watched the fire destroying the building and causing damage in excess of £100,000 (Courier-Mail 19 Feb. 1954).