Chapter Seven JESUS CHRIST TODAY

We are in a period of christological ferment unmatched since the first century. Like the first-century church reflected in the New Testament we once again have a pluralism of christologies or different ways of formulating Jesus Christ's significance and identity while remaining united in the confession of the one faith. Like the Christians of the first century, we too are being called to write the good news in an idiom suitable to our time and place. . . . We must name Jesus Christ again and claim him again for our own people, so that a living christology will be handed on to the next generation into the twenty-first century. [ Elizabeth Johnson, Consider Jesus: Waves of Renewal in Christology (New York: Crossroad, 1990), 145f. ]

Change in the way Catholics began to think about Christ occurred with the Second Vatican Council's call for the church to 'dialogue' with the joys and sorrows, hopes and fears, of the modern world. Pope John XXXIII, who called the Council, recognised the church's need to move beyond the 'ghetto mentality' in which Catholic identity was formed 'against' the world of modern culture and other religions. Pope Paul VI spoke of the responsibility of speaking the Christian message to the modern world in ways that it could understand. Inevitably, the 'opening of the windows' of Catholicism to 'dialogue' with contemporary thought and culture, and with other religious traditions, brought new questions to bear on the meaning and significance of Jesus Christ for our age.

The result has been an explosion of christologies: 'a period of christological ferment unmatched since the first century'. These different and often diverse approaches to the mystery of Christ need to be seen against the backdrop of modern experience. If the 1960's was a decade of rebellion, it was also a time of hope and optimism in the future; the 1970's was, for many Australians, a period of idealism, experimentation and disappointment (often symbolized by the rise and fall of the Whitlam government); the 1980's has become known as the decade a crass materialism, greed and lost fortunes; and the 1990's a time of careful restructuring and cautious preparation for a precarious future in a world threatened by religious fundamentalism, ethnic wars and ecological disasters. Although we need to be careful in making such generalizations, we can rightly speak of a certain 'spirit' operating within an age--and note that this 'spirit' has the uncanny knack of influencing the way we think about the world and reality.

It is helpful to read such contemporary human experiences according to three distinct models or paradigms. Each model represents a significant turning point or transition in modern history; and it provides us with a different understanding of the Christ-mystery. The first is the transcendental or idealist paradigm which highlights the importance of individual human experience in our knowledge and understanding of reality. It depicts an understanding of Christ that resonates with our deepest human longings. The second way of viewing reality--the practical or political model--is more sensitive to negativity, suffering and evil that operate within the world, society and human lives. Within this paradigm, we are presented with a confronting and liberating Christ. There is yet a third transition that can be called the global paradigm: it reflects on the world and human existence according to our need for a new type of consciousness that is genuinely 'world'-oriented. These 'different ways of reading the world' provide different starting-points, questions and issues that influence the kind of christological investigations we make and the sort of christological answers we receive.

Throughout the 1960's and 1970's transcendental and narrative christologies (first paradigm) challenged the way most Christians thought of Jesus Christ by insisting on his genuine humanity and his historical life as a first-century Palestinian Jew. These christologies coincided with an optimistic belief in human life and progress: with the aid of science and technology, it was thought, all or most of the world's problems (such as poverty and disease) would be solved in time. Even the 'problem' of unravelling the life-story of Jesus could be 'solved' by applying 'scientific' techniques to the Scriptures. In this context, Jesus' humanness was no longer something to be covered over, but a source of life and hope for Christians and all people of goodwill. The 'humanised' Jesus was a more 'accessible' Jesus who related to people's everyday concerns.

By the 1980's a new mode of thought (second paradigm) had begun to emerge in Jesus-studies. These newer histories and theologies of Jesus noted that all christologies reflect the historical, political and cultural biases of their authors. In particular, it was noted that, when Jesus is interpreted from the vantage point of the poor and oppressed, we see a more radical and subversive Jesus who is caught up in the politics of his time. Such political christologies insist there can be no pure Jesus-studies: the Christ-mystery is always understood according to the 'context' of enquiry. Moreover, every context reflects particular social evils and political distortions whether these be the inequities and dehumanizing patterns of wealthy, Western nations (the political Jesus), the poverty and corruption of Latin American and other third-word countries (Jesus Christ liberator), or the widespread experience of gender-division that oppresses women (advocate for women). These christologies understand their role in terms of challenging distorted social systems and duhumanizing attitudes in the name of the liberating Christ.

As we head towards the third millennium, there is increasing awareness that the claims of Christianity--such as the claim that Jesus is the 'universal saviour figure'--need to be read in terms of other religious traditions. What, for example, is the relationship between Jesus and Mohammad, or Jesus and the Buddha? Moreover, it needs to be asked to what extent traditional expressions of belief in the Christ-mystery have been responsible for Christian anti-semitism? In the light of such questions, there is an attempt to develop more global christologies (third paradigm) with the aid of cross-cultural and interreligious dialogue.

We now turn to a more detailed discussion of contemporary christologies according to these three paradigms or ways of reflecting on Jesus Christ through the lenses of human experience, political reality and the emerging global situation.

Jesus Christ and human experience This approach to christology begins with the question: what does it mean to be human? In light of this reflection, it then asks: how is it possible to account for our faith in the historical figure, Jesus of Nazareth? It is, if you like, the study of Jesus Christ through the study of human experience--sometimes called 'christology through anthropology' [ This anthropological approach to christology is developed by Karl Rahner, Foundations of Christian Faith (New York: Seabury, 1978), esp. ch. 6; also see the essays expounding Rahner's christology in Leo O'Donovan, ed., A World of Grace (New York: Seabury, 1980), chs. 7 & 8 ]. The fundamental question being addressed is whether or not it is meaningful for human beings today to believe in the story of Jesus that has been handed down to us in the Christian tradition. In other words, is christology anything more than mythology? Or is it, as Christian faith claims, the answer to our deepest human longings for peace, justice and love. In more traditional language: how does contemporary thinking understand Jesus as Christ, Lord and Saviour?

As indicated, this approach begins with the question of what it means to be human. Many centuries ago, Aristotle defined the human as a 'rational animal'. Modern existentialist thought takes a different tack: to be human is to be involved in a dynamic process of living, growing, dying. We live in an evolving universe that is thrust towards an open future; humans are in integral part of this dynamic cosmos. More than this, humans represent the moment in which the cosmos attains self-consciousness. More than any other (known) creature, humans are this mysterious unity of matter and spirit enabling them to express the fundamental unity of the entire cosmos.

To admit that we live within the mystery of an evolving universe is also to admit that we live in relationship to the ultimate mystery--what most religious traditions call 'God'--who is the source and goal of all creation. To be genuinely human, then, is to be radically related to this divine mystery--even if many people today are reluctant to use the name 'God'. It is finally not a matter of rational thought or clear understanding or even the ability to name this God which accounts for our humanness. Whether we 'know' it or not, the divine mystery so pervades the cosmos and human experience that we 'live' within this mystery as fish live in the sea. Karl Rahner, who develops this anthropology, says that our small islands of knowledge are always grounded in the sea of infinite mystery. [ See Karl Rahner, Foundations of Christian Faith (New York: Seabury, 1978), ch. 2; and M. Buckley, Within the Holy Mystery in L. O'Donovan, ed., A World of Grace (New York: Seabury, 1980), ch. 3. ]

Once we situate ourselves within this dynamic or evolutionary understanding of the world and humanity, a number of other points follow. A major one is the realisation of human finitude. All human knowledge and experience is limited by time, place and culture. We can only hope to know and understand the world and ourselves according to our particular, historical situation. We might even say that, for us, humanness is much more a question than an answer. Nonetheless, we are called upon to live authentic human lives and make responsible human choices in the face of this unknown. In fact, to be human means to be involved in the process of becoming more human through the authentic use of human freedom--and despite the fact we often do not know where our decisions will lead us.

A further aspect that relates to modern experience is the tendency to reject the voices of tradition and authority unless they are also validated by one's 'own experience'. People are less inclined to keep on believing something simply because their parents or grandparents believed it. This becomes more understandable given the speed with which things are changing today. And as Australians, living in an increasingly pluralistic society, it would be naive to expect our children not to question the political, social, moral and religious values of their parents. If they accept the truth of these values, it will only be on account of their acceptance that these values are true and life-giving for them. Jesus Christ will be warmly embraced, outwardly rejected or indifferently ignored in accordance with how he relates to people's experience. He will not be simply accepted as the saviour-figure because of the power of tradition.

The cosmic Christ and saviour-figure Insofar as this analysis of human experience is a true indication of being human in the modern evolutionary world, we then move to the question of the meaningfulness of a saviour-figure. After all, what is it that human beings need saving from? In answer to this question, we can then ask in what way Jesus Christ fulfills the criteria. In earlier times, the answers seemed more simple: people felt the need to be 'saved' from the devil and sin. It was understood that this was why Jesus Christ came into the world. However, this seems to us today, at best, a partial response to people's existential concerns. It may well be argued that people need to rekindle their sense of sin and guilt in order to appreciate the saving role of Jesus Christ. Nonetheless, it may be more helpful to admit that people need to be able to relate to Jesus Christ in terms of their own experience of the world and life today. This is the approach transcendental christologies follow.

In the light of our modern cosmology and anthropology we will want to situate the saviour-figure in terms of an evolutionary understanding of the world in which the human being is called to authentic existence. The pioneering work of Teilhard de Chardin fits in here. He not only saw that the universe is a dynamic unity of matter and spirit; he also recognised that the evolutionary thrust of the universe from matter to spirit was due to the divine empowerment within creation. He further identifies that power with Jesus Christ who is the alpha and omega, the beginning and end, the origin and culmination, of all creation (see Colossians 1:15-16; Ephesians 1:9-11). Jesus Christ also represents the climax of divine creation and human history, the one in whom God's plan for the entire universe reaches its peak. Evolution, for Teilhard, is explicable only in terms of this dynamic activity of the cosmic Christ who is also the human-historical Jesus. [ Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Christianity and Evolution (New York: Harcoourt & Brace, 1969); The Phenomenon of Man (London: William Collins, 1977); The Divine Milieu (London: Collins, 1960). See also, Denis Edwards, Jesus and the Cosmos (New York: Paulist Press, 1991); The God of Evolution (New York, Paulist Press, 1999). ]

In terms of human experience, Teilhard would suggest that the striving for world peace and human community are indications of the power of Christ operating within the created order. Christ 'saves' the cosmos from endless multiplicity and fragmentation which threaten the evolutionary impulse towards unity. At a human level, this means being 'saved' from the diabolical realities of sin and evil by the superior power of (divine) love. Whereas Teilhard was a scientist, and so wants to bridge the world of science with Christian faith, it is Karl Rahner who provides us with a more direct account of a christology based on contemporary views of the human person and human experience.

For Rahner, the human being's thrust towards the future, the inifinite, the divine mystery, is expressed in both general and specific terms. Generally, the human person lives in hope, acts with courage, dares to forgive and, above all, tries to love--all this despite the evident fact that despair, selfishness and all kinds of human guilt threaten to engulf our human lives. At a more specific level, Rahner asserts that human beings search in history for an answer to their quest for meaning and fulfillment. In other words, it is not adequate to simply hope that the universe is trustworthy or that our deepest human yearnings will be fulfilled. We seek confirmation of these realities in a saviour-figure who both shares our human experience (one like us) and yet whose human longings have already been achieved (the divine goal).

Rahner maintains that all authentic human life is lived with at least hopeful anticipation of this saviour-figure who assures us that our human longings for the divine mystery are not in vain. Moreover, the true saviour-figure will need to be one who lives life in full human freedom and yet in total surrender to the divine mystery. Both these dimensions--human freedom and surrender to God--are necessary since they are integral to our human identity and authenticity. It is also necessary that the historical life of the saviour-figure be given the divine seal of approval, that is, that the saviour be loved and accepted by God in a definitive way. The saviour-figure, of course, is perfectly embodied in Jesus of Nazareth who 'is one like us in all things but sin' while also being the specially annointed and chosen one of God or, indeed, God's own Son. In Christ Jesus, then, God both respects human freedom and responds to our human longing to be loved irrevocably by God.

This approach to christology through reflection on human experience in an evolutionary universe also situates the Christ-event as the high-point or climax of all creation and history. God does not act in the world in a way that violates the integral processes of the cosmos or the true freedom of human beings. To the contrary, the mystery of the Incarnation is nothing other than the confirmation that the unifying forces of the cosmos and the human yearnings for God are achievable through Christ because they have already occurred in Christ. Creation and salvation are not two separate and disconnected events in the history of the cosmos. Rather, they are part of the one movement of God's self-communication to the world which reaches its fulfillment and perfection in the divine mystery.

Jesus Christ and political reality Political christologies also begin with reflection on human experience but, rather than focus on the 'transcendental longings' of human beings, they point to the dark realities of suffering and oppression that inscribe our earthly existence. The real world in which humans live, it is suggested, is a world marked by torture and death-camps, ecological crises and starving peoples, the experience of the holocaust and the threat of nuclear war, the exploitation of women and the near-extermination of entire cultures, gross misuse of political power and sheer capitalistic greed. These forces of negativity and corruption--the forces of evil--impoverish whole societies of human beings and threaten our very planet with extinction.

Consequently, political christologies have no difficulty in admitting that the world stands in need of 'salvation'. Their question is not whether human beings are in search of a saviour-figure but, given our evident need to be saved and liberated, how does Jesus Christ fulfill this role? How does the life and ministry, death and resurrection, of Jesus of Nazareth enable us to transform this situation of 'death' into a situation of 'life'? And there is a sense of urgency in their questioning.

The approach could be called 'christology through sociology' because it reads human experience in terms of the social, economic and political realities which shape human lives. [ Two classic texts, both from a South American perspective, are: Leonardo Boff, Jesus Christ Liberator (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1978); Jon Sobrino, Christology at the Crossroads (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1978). ] It specifically rejects the evolutionary optimism of a Teilhard de Chardin or Karl Rahner. It points to the 'political' realities of twentieth century life in which there has been more human suffering and death than in the entire history of the world. It develops its christology in the light of the three great twentieth century crises of Marxism, Auschwitz and the Third World. Following Marx, what is important is not theory but praxis (critical reflective action); following Jesus Christ, what is important is not a theology of Christ that 'explains' the world, but practical Christian discipleship which 'changes' the world and 'liberates' human beings.

The political Jesus The first type of political christology was worked out in the affluent cultures of wealthy western nations which are heirs to Christian faith. [ For two examples of notable European 'political theologians' see: J. B. Metz, Faith in History and Society (New York: Seabury, 1979); Edward Schillebeeckx, Jesus in our Western Culture: Myticism, Ethics, Politics, (London: SCM, 1987). ] Consequently, it is a christology which could well find a home in the Australian context. It sees its task as challenging the bourgeois religion of middle-class Christianity which is too often devoid of a sense of the radical, social-justice demands of the Gospel. Recognising how Jesus' own ministry was a political as well as a religious challenge to the status quo of his day, these political theologians ask if the churches have not lost sight of the intimate connection between faith and politics which should be at the heart of Christian life and mission. If anything, it is suggested, Christianity has so readily identified with the capitalist society of money, power and greed, that it has turned Jesus Christ into a respectable supporter of white, European (and Australian) middle-class values. Where is the dangerous Jesus who so fearlessly opposes those who work against the kingdom-community of justice, love and peace?

In fact, all political christologies focus their reading of Jesus in his prophetic proclamation of the reign of God: 'The reign of God is at hand: repent and believe in the gospel' (Mark 1:15). We have seen earlier that this proclamation was inclusive of all, but especially of the 'little ones': the poor and the persecuted, those who suffer and mourn, the ones who work for justice, the merciful and the peace-makers (Matthew 5:3-10). Political christologies emphasize that these kingdom-values involve both personal and social conversion. They challenge the violence and selfishness that oppress human lives and they invite people to a new way of life together. The church too stands in need of ecclesial conversion: to return to the kingdom-values by confronting its own tendencies to opt for the comfortable 'bourgeois' life.

What is it about these bourgeois values that is so opposed to the kingdom values of Jesus and the gospels? According to German theologian Johann Metz, bourgeois culture is a culture of apathy and lost memory: people have lost the ability to feel sorrow and guilt; and they no longer have the capacity to grieve suffering and death. In the absence of these human and humane qualities, bourgeois culture is unable to express pathos, love and compassion. Caught in a time-warp with the foreboding sense of a 'faceless evolution', Metz thinks that bourgeois life has lost any real hope of changing things or making a different future in which the human being counts. Human life has become banal, predictable and boring. Having been bombarded with technology--and now totally dependant on it--, affluent cultures have lost the ability to be shocked or surprised (even by the images of devestation and death on our television screens).

For Metz, these bourgeois attitudes are not so much directly opposed to kingdom values as they are deaf to their life-giving power. Consequently, he seeks to confront bourgeois society with the dangerous and subversive stories of Jesus who challenged the society of his time with words and actions of crisis. Recalling a statement of Jesus in the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas--'He who is close to me is close to the fire'--Metz wants us to be shocked, surprised and confronted by the human figure of Jesus who boldly proclaimed the kingdom in the face of opposition and was then led to his death in a state of utter human depravity. Our own identification with the dangerous and suffering Jesus will hopefully shock us out of our complacency, enable us to feel empathy with the victims of history, and then empower us to be proclaimers of God's reign in our own lives, the church and society at large.

Political christology is, then, primarily a christology of discipleship. It calls for a deep, personal conversion to the kingdom values in a world where justice, love and peace are suffocated by the dominant forces of industrial capitalism. Seeking to unlock the hardened hearts of mainly western, middle-class Christians, it challenges them to true compassion and solidarity with the victims of history by entering into and imitating Jesus' own dangerous story. This is a story of hope for humanity insofar as the story of Jesus includes the mystery of the resurrection. However, as long as social justice and true humanity elude our world, the 'saving power' of Jesus will not be the transforming reality that Christianity proclaims it to be.

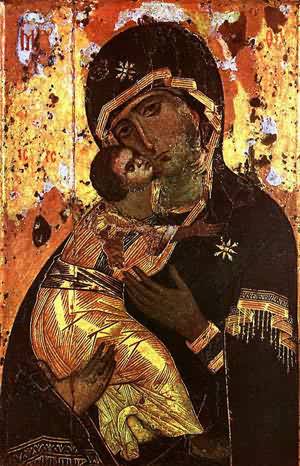

Jesus Christ liberator The need for human liberation is most poignant in so-called third-world countries where poverty, corruption and all forms of human injustice reign supreme. The specific image of Jesus the liberator arose in small base-community churches of Latin America in response to the extreme violence (tyrannical governments, death squads, dire poverty and mass starvation) which seemed to be the fruit of some four hundred years of 'Christian colonization'. It began to be noted that images of the kingly, imperial Christ were used to justify an unjust social order in which the wealthy few used their power to keep the natives and peasants in their situation of poverty and unfreedom.

Just as 1968 was the year of peace marches and anti-war demonstrations in wealthy, capitalist 'northern nations' (notably Europe and North America--and also Australia), it was also a time of raised hopes and consciousness in the peoples of the poor, dependant 'nations of the south' (notably Latin America). 1968 was the year that Paulo Friere published his book Pedagogy of The Oppressed which provided a method for empowering the poor to take up their own struggles (he called this the 'conscientization of the poor') [ Paulo Friere, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1970). ] In the same year, the Catholic bishops of Latin America met in Medellin, Columbia, and produced a challenging document on the situation of poverty and injustice that was rife throughout the Continent. Specifically, the Medellin document recognised the intimate link between 'liberation' and 'redemption': they proclaimed that 'all liberation is an anticipation of the complete redemption brought by Christ'. The bishops also spoke of the priority or 'option for the poor' which marked Jesus' own earthly life and should therefore be central to Christian life and ministry.

Soon after Medellin, the Peruvian Jesuit, Gustavo Gutiérrez published his work entitled A Theology of Liberation. [ Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology of Liberation (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1973) ]. Since that time, there have been hundreds or perhaps thousands of works on 'liberation theology'. These have sprung up not only in Latin America but also in Africa, Asia and among indigenous and other impoverished peoples throughout the world. Liberation christologies reflect on Jesus Christ from the perspective of the suffering of particular oppressed groups. They begin by listening to the voices, the struggles and the outcries of the 'disfigured children of God'. These voices provoke a sense of 'religious outrage': if God is a God of total goodness and love, and if Jesus has come to 'save' us and 'redeem' the world, then all people have the responsibility to change the situation of oppression into a situation of liberation. To refuse to challenge the unjust system is tantamount to being complicit with evil.

Liberation and other political christologies are highly conscious of the social and political nature of human existence. Redemption and sin, grace and guilt, salvation and evil are embedded in the very fabric of human society. It is not only individual people who are good and just or sinful and inhuman; social systems (whether capitalist, socialist, democratic or monarchical) are also inherently moral or immoral, just or unjust, life-giving or death-dealing. Typically, social systems will exhibit a mixture of goodness and evil. Nonetheless, any social system which promotes violence or walks on the heads of people's dignity needs to be called 'inherently evil'. In order to understand this evil or 'social sin', it is important to uncover the root causes through social analysis. Why in some countries, for example, do 5% of the people control 90% of the wealth? Is this an economic or class based evil? If so, marxist socio-economic analysis may help. Why are indigenous people (such as Australian aboriginal people) so often dehumanized and made voiceless? Is this due to racism? If so, it needs to be named, confronted and changed.

However, it is not only society that stands in need of critique. The Christian tradition itself can be a cause of oppression. How often in Christian history has the suffering and death of Christ been used to keep people in their situation of powerlessness? How many sermons have promoted the idea that to be a 'good Christian' it is necessary to suffer quietly and passively as Christ did? How often has the image of the kingly Christ been used to justify the tyrannical misuse of power on the grounds that obedience to all civil and ecclesiastical authority (even if corrupt) is obedience to the will of God. Liberation christologies acknowledge that false images of Jesus Christ are part of the history of oppression that has been especially evident in the 'colonial era' when the Gospel of the Church and the Sword of the State were too often hand in hand.

In marked contrast to the passive Jesus and the imperial Christ is the image of Jesus Christ the liberator. Liberation christologies focus on the historical Jesus of the Gospels who was neither a passive victim nor a dominating Lord. The liberationist Jesus is depicted as challenging the unjust powers of his day, healing the sick and broken-hearted, forming community with the marginalized. He is involved in conflict, rejection and struggle in the name of the living God who alone is king. The 'option for the poor' is seen to be at the heart of Jesus' own ministry of proclaiming and enacting the reign of God. Among key gospel texts which are used to highlight Jesus' liberating ministry is his recitation from the scroll of Isaiah:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has appointed me to bring good news to the poor, to proclaim liberty to captives, to give the blind new sight, and to set free all who are oppressed. (Luke 4: 16-18)

Significantly, in Luke's Gospel, this passage is set at the beginning of Jesus' ministry. It is as if everything that follows in Jesus' life takes it cue from here. Whatever else about Jesus' public life, Luke understands that it has special relevance for the poor and victims of history. Luke's entire Gospel can be read as a liberation christology in which the powerful and mighty of the earth will be overthrown by the little ones (see the Magnificat, 2:46-55).

The suffering and death of Jesus are read as liberating acts of God through Jesus. Jesus does not walk blindly and passively to his death. Rather, his death comes about as the result of his active engagement with the forces of evil and injustice which pervaded the society of his time. Of course, Jesus was a victim to those powerful forces. Yet, even in the face of death, he retains his powers of compassion and love: 'Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing' (Luke 23: 34). Jesus nowhere evades his active mission of love and service--had he done so, he may well have evaded the tragic circumstances that led to his crucifixion and death. Consequently, from a liberation perspective,

the cross reveals that God identifies with the one unjustly executed rather than the rulers. Far from legitimating suffering, the cross . . . shows victims that God is in powerful solidarity with them in their suffering, and opens the possibility of their own active engagement, both interiorly and exteriorly, against the forces of oppression. [ Elizabeth Johnson, Consider Jesus: Waves of Renewal in Christology (New York: Crossroad, 1990), 92. ]

The resurrection of Jesus is seen as the final confirmation that God is stronger than all forces of evil, negativity and death. It tells us that evil does not have the last word; equally, it commissions us to oppose all expressions of evil--personal, social and political--that we encounter in our world.

Liberation christology strongly emphasizes the importance of praxis, that is, critical action on the basis of reflection and critical reflection on the basis of action. In other words, it demands getting one's hands dirty through solidarity with the victims of the world in their active opposition to injustice. It may well demand, as with Jesus and the Christian martyrs, that we put our very lives on the line. However, liberation theology is not a purely social action movement. This is where critical reflection is paramount. Such reflection must begin and end with Jesus Christ who alone is the liberating Word of God in our midst. It is this living, liberating Word that reunites us to the servant christology of the scriptures and provides us with a new image of God for our time: a God who is especially present in the poor and oppressed. Liberation christology tells us that we can meet this God only through our identification with Jesus in the poor.

Advocate for women In light of today's reflections on the status of women in society and religion, Christian theology is led to examin its own heritage and, as far as possible, to investigate Jesus' own attitudes to women and gender equality. These are crucial issues in view of the fact that, throughout Christian history, the church has often portrayed women as of less importance than men. Tertullian, for example, taught that 'the curse of God' was on women; Augustine claimed that 'only males' were made in the 'complete image of God'; and Thomas Aquinas held that 'woman is a misbegotten man'. [ Elizabeth Johnson, Consider Jesus: Waves of Renewal in Christology (New York: Crossroad, 1990), 101. ] Much of this thinking was based on a one-sided and ultimately false reading of Original Sin which saw Eve as the seducer of a less culpable Adam. This is ironic insofar as it portrays men as victims of women's sexuality when it is patently obvious that, for the most part, it is men who abuse, exploit, batter and rape women for their own sexual gratification.

Feminist christologies follow a similar pattern to liberation christologies. First, they seek to understand and name the situation which oppresses women. They notice two significant factors. Most human societies are inherently patriarchal, that is, most positions of political power and social prestige are reserved for men; typically, women are at the bottom of the pile, subordinate to and dependant upon better-paid, better-fed and better-educated men. This social structure is supported by what is termed androcentrism (from the Greek 'andros' meaning adult male) where the 'norm' for 'humanness' is 'maleness'; it follows that women are less human than their more 'normal' counterparts. Taken together, patriarchal structures and androcentric thinking lead to what feminist theologians name 'the sin of sexism'. This leads them to critique the ways in which the Christian tradition has contributed to the subordination of women.

The second step involves the critique of sexist interpretations of Jesus Christ. Noting that the historical Jesus was a male human being, feminist theologians claim that Jesus' maleness has been used in such a way as to falsify both the reality of God and the reality of being human. Certainly, in Christian belief, Jesus reveals God to us in a special way; and, certainly, both Jewish and Christian scriptures speak of God in male terms such as king, male warrior, or Abba Father. However, only a fundamentalist reading of scripture could take these images or metaphors in such a literal way as to imagine God being male. God is evidently beyond gender.

Nonethless, it is important to recognise that the scriptures do speak of God in female form as mother, midwife, nurse, mother-hen brooding over her young, or Sophia (Wisdom). Similarly, Jesus often uses female images when speaking of the reign of God: it is women who knead the dough and go in search of the lost coin. The point here is not that God is literally female, but that these female images of God have been neglected in the Christian tradition. This is why many Christians still find it difficult to speak of God in anything but male terms. It may be said that Jesus himself uses the male term Abba and that we should do likewise. However, if we accept the whole of Jesus' teachings on the reality of God, we will notice that the characteristics of this God--compassion, love, intimacy, friendship, forgiveness--are probably much more 'feminine' than 'masculine'. As well, the scriptural image of God as (Holy) Spirit ('ruah')--hovering, creating and renewing the earth--especially lends itself to the feminine 'she' rather than the masculine 'he'.

The other part of this critique concerns the way in which the gender of Jesus has been falsely interpreted to indicate male superiority. It has been suggested, for example, that only men can truly imitate Jesus. It is not a long step from here to say that Jesus' saving power is only fully available to men. Evidently, the mystery of the Incarnation means that the Word became flesh in the human reality of Jesus who was Jewish, who spoke Aramaic, who was a carpenter, and who was male. These historical factors were not insignificant to the human Jesus: they defined his world. However, if the Incarnation has meaning for the world, and if christology has any meaning at all, the issue of Jesus' gender is no more significant than the issue of his nationality. Moreover, if women are genuinely human, and if the God of Jesus is the God of love and salvation, then Jesus' embodiment as a male is a matter of historical contingency. As well, if Jesus is to be experienced as the saviour of women and men today, he needs to be understood as one in whom femininity and masculinity are authentically integrated.

A feminist liberation christology will need to show that Jesus is such a person. This is the third and final step of the process. It shows that Jesus' programme of justice, peace and love is genuinely inclusive of all people. Despite the patriarchal structures which operated in the society of Jesus' time, the various stories reported to us in the Gospels show no androcentric attitudes in Jesus. In fact, Jesus is remembered and reported as treating women and men with equal respect and dignity. He even goes out of his way to stand up against oppressive laws and attitudes which denigrated and ridiculed women. Examples of this include: Jesus' defence of the woman caught in adultery (John 8:1-11); his welcoming acceptance of the woman who visits the house of Simon the Pharisee (Luke 7:36-50); his challenge to the abusive divorce practices of the time which gave all the say to men and none to women (Mark 10:1-12; Matthew 5:28-32); and Jesus' attacks on those who oppressed widows (Mark 12:38ff).

Jesus shows no concern for following the social and religious taboos of his time when these interfered with his ministry of proclaming God's inclusive reign of forgiveness, love and compassion. This is evident in his healing ministry where he directly challenges various taboos regarding what is 'clean' and what is 'unclean'. For example, it was generally accepted that women's blood was 'unclean'. However, on one occasion, Jesus responds to the touch of a 'constantly unclean' woman (she had been haemoraging for twelve years) by demanding she come forth to praise her faith and place her as a model of human trust in God (Mark 5: 25-34). Jesus does not simply heal the physical malady of the woman. More poignantly, he returns to the woman the lost dignity that human prejudice had denied her. There are many other examples--touching a dead girl, mixing with female prostitutes, talking to foreign women, befriending women as his equals--where Jesus' words and actions confront the sexism of his day.

It is not only that Jesus 'treats' all people--women and men, adults and children, the sick and the healthy--with equal respect and dignity. He also 'empowers' them to take up their own authority as authentic persons. One of his more radical moves in this regard was the call of women to be disciples. Whereas the patriarchal system worked to keep women in a position of inferiority, to be mothers and home-makers, Jesus teaches that the mission of the kingdom takes precedence over social and family patterns. There are plenty of examples where women like Joanna, Mary Magdalene, Martha and Mary, and Jesus' own mother, Mary, are empowered by Jesus to take on discipleship-ministry. This pattern is highlighted in the stories of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus where it is women rather than male disciples who are centre-stage. Feminist scholars also point to the vigorous ministry that women played in the early church as missionaries, teachers, healers, leaders of community-churches, and the like.

There is enough here to indicate that Jesus can be reclaimed today as 'advocate for women'. He does this through his proclamation and embodiment of the kingdom-community of justice, love and peace. In this community, no-one is to be excluded or considered inferior on account of race, social position, or gender. Where traditional attitudes, laws and taboos impede this call to rightful dignity and equality, they are to be challenged and discarded. Feminist readings of the scriptures show how patriarchal structures and androcentric attitudes begin to blunt the radical nature of Jesus' mission of universal inclusiveness. In this context, what is remarkable is the way in which the scriptures contain so many 'memories' of Jesus' advocacy for women. These memories confront all non-inclusive theologies which would deny women true social, political and religious equality.

Saviour of the world The 'global turn' in theology is provoked by the overwhelming question of what it means to call Christ the 'universal saviour-figure' in an age where genuine tolerance and respect for all people, cultures and religions is seen to be both a generally human and specifically Christian virtue for our time. Various contemporary authors speak of a breakthrough in human experience and consciousness that amounts to the discovery or realisation that humans live in a single, interrelated world. [ See, for example, Raimon Panikkar, The Cosmotheandric Experience (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1993). ]

This new story of our human, global co-existence is only beginning to be written. For some, it will be a story of great beauty and promise as diverse cultures and religions begin to meet at new levels of depth and meaning. Others see the story in more pessimistic terms as they contemplate the profound inability of human beings to celebrate their ethnic, ideological and religious differences.Quite evidently, Christian intolerance toward other religions has been an unfortunate aspect of Christian history. [ As one example of Christian intolerance towards Judaism, see Dan Cohn-Sherbok, The Crucified Jew: Twenty Centuries of Christian Anti-Semitism (London: HarperCollinsReligious, 1992). ] Moreover, such intolerance is still prevalent today in various parts of the globe. Theologians ponder the question of how belief in Jesus the Christ has contributed to this state of affairs. And they wonder how Christian belief can be reformulated in a way that is both faithful to belief in Christ as saviour and yet genuinely respectful of the freedom of other people to live according to their own cultural and religious traditions. After all, the scriptures themselves teach us that 'God wills all people to be saved' (1 Timothy 2:5). The Second Vatican Council applied this teaching to other religions by declaring that they often reflect the divine ray of truth and so can be authentic paths of salvation. [ Declaration on the Relations of the Church to Non-Christian Religions, article 2. ]

However, we are still left with the christological question of how Jesus Christ is to be understood as saviour of the world. [ A good overview of different theoretical positions on this question is Paul Knitter, No Other Name? A Critical Survey of Christian Attitudes toward the World Religions (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1985). ] The traditional approach to this question can be called exclusivism because it generally 'excludes' the reality of the divine presence outside of Christian baptism and the explicit confession in Jesus as Christ, Lord and Saviour. It follows that other religions are false and other saviour-figures are, at best, merely models of how to live a reasonable human life. Christianity, it was maintained, is the 'supernatural' religion whereas other religions are purely 'natural'. This approach was often based on an over-literal reading of the non-scriptural text which stated: 'Outside the church there is no salvation'. Nonetheless, it must be stated that most theologians operating within this model left room for the 'mystery of God's love' which is available, albeit in exceptional circumstances, to 'pagans and the unbaptised'.

Well before the Second Vatican Council, most Catholic theologians were already beginning to adopt a more optimistic and inclusive understanding of Christ's role in salvation. The best-known expression of this inclusivism is Karl Rahner's 'anonymous Christianity' [See Karl Rahner, The One Christ and the Universality of Salvation, Theological Investigations 16 (New York: Seabury, 1979), 199-224. ] His position flows from his notion of the cosmic Christ which we viewed earlier. Fundamentally, there is one God, one universe and one saving mystery, Jesus Christ, who mediates God's love and salvation to the world. Christians are those who know Jesus Christ in an explicit way. However, the saving mystery of Christ is not reserved for the church and its members. It is present throughout the universe or cosmos and manifests itself in the lives, cultures and religions of people everywhere. In fact, for Hindus or Buddhists, for example, the saving reality of Christ's presence in their religions means that they achieve salvation precisely by being good Hindus or good Buddhists. Here, they come to 'know' Christ in an implicit rather than an explicit way.

Another example of the inclusivist approach is that of Catholic priest and interreligious scholar, Raimon Panikkar, who once made the startling comment that he went to India a Christian, found himself a Hindu, and became a Buddhist--all without ceasing to be a Christian! [ Raimon Panikkar's most significant work outlining an inclusivist approach is The Unknown Christ of Hinduism (rev. ed., Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1981). See also, The Jordan, the Tiber, the Ganges: Three Kairological Moments of Christic Self-Conscciousness in his A Dwelling Place for Wisdom (Louisville Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1993) 109-159. ] Panikkar had the advantage of being born of European-Christian and Asian-Hindu parents. He proposes the interesting idea that Jesus' identity as Christ and Lord should not preclude other possible ways of naming 'the saving Supername'.

In other words, he is suggesting that the Word of God is capable of more than one Incarnation. This allows for the possibility of the incarnate Word being present in the saviour-figures of other religions. Panikkar likens the world's religions to the various colours of the rainbow: each reflects a different aspect of the one divine saving mystery that Christians call the Christ and rightly identify with Jesus of Nazareth. However, Christ cannot be limited to any one religion or even to Jesus of Nazareth since 'every being is a christophany, a showing forth of Christ'.

Some scholars today suggest we need to move beyond both the exclusive and inclusive approaches. For them, the whole attempt to ascribe to Jesus Christ a universal saving role has resulted in an attitude of Christian superiority that has been historically disastrous for people of other traditions. Although this position is sometimes called relativism, it does not say that any religion is necessarily as good as another, or that all religions are equal, or that all saving figures perform the same role. It still affirms that faith in Jesus Christ is necessary for Christian salvation. However, it does not want to impose Christ on other peoples or to suggest that the truth of their religions is to be measured against Christianity. After all, it was this kind of thinking that led Christians to develop such negative attitudes towards the Jewish people 'for turning their backs on Christ'. The solution that is advocated is to say that Jesus Christ is a universally relevant historical-figure (in much the same way as Moses or Mohammad) but an ultimately specific saviour-figure.

None of these approaches is without difficulties. Exclusivism can and should be discarded as being against the central Gospel teaching of God's universal saving presence. Inclusivism is a better option though it is problematic in the way it imposes Christian understanding on other people's experiences. Others critique inclusive approaches on the grounds that they do not adequately acknowledge the profound unity between the Christ-mystery and the historical Jesus of Nazareth. Likewise, relativism has the significant difficulty of showing itself compatible with the fullness of Christian revelation. Perhaps the major difficulty is the Western-Christian tendency to want a completely rational solution to what is, after all, the profound mystery of creation. Jesus himself did not come to give Christians a kind of secret knowledge of the universe. Rather, he entered into the reality of people's lives and challenged them to the new community of justice, love and peace in the name of the living God. Today, we stand at a point of human history where a new global community needs to be founded on the basis of interreligious and cross-cultural dialogue.

There is a story told in Mark's Gospel (7:24-30) where Jesus is confronted by a foreigner, a Syro-Phoenician woman. Jesus' reaction indicates his initial discomfort with her: 'It isn't right to take the children's food and throw it to the dogs'. However, the woman is persistent and retorts: 'Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children's left-overs'. By now, Jesus' interest is captured to the point that his entire attitude changes. He commends the woman for her insight, heals her daughter and, in Matthew's version, praises her for such great faith (15:28). This story is sometimes used in feminist christologies to show how Jesus came to a new awareness of the importance of women in the kingdom-community. It may also be read as a moment in Jesus' ministry where he comes to a new consciousness of the importance of the 'foreigner'. His dialogue with this foreign woman changes the way he thinks and acts. Christianity stands in a similar position with regard to the 'foreign' religions. It is still the moment of discomfort. However, like Jesus, Christians need to enter into the dialogue, to be open to the challenge it brings, and be prepared to think and act differently as a result of the encounter.

In acknowledging Jesus as the Saviour of the world, Christians need to hold in tension two distinct principles: Jesus is Christ, Lord and Saviour, the one who mediates the God of all love and goodness to the world; other people, cultures and religions experience God and 'salvation' by other names (or by no name) and with different understandings. Our mission as Christians is wrongly understood if it amounts to convincing the other person to our way of seeing the world. Our mission is certainly to testify to the reality that our experience of grace and salvation, truth and goodness, forgiveness and love, comes to us through the one whom we name the Christ and who is identified with Jesus of Nazareth. However, as Karl Rahner once said, proclaiming Christ is not the same thing as informing people that the continent of Australia exists! It is not a matter of intellectual knowledge, but of the knowledge of the heart. Heart-knowledge cannot be imposed: it must be shared; it must be two-way. Christian mission is first and foremost a call to human authenticity and community.

CHAPTER SIX Back to Christology Home Page CHAPTER EIGHT