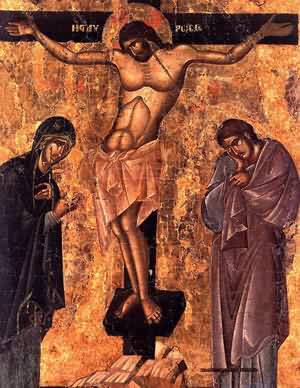

Chapter Four JESUS' CRUCIFIXION AND DEATH

The killing of Jesus It is safe to say that Jesus was not crucified because he taught love and forgiveness or because he set about debating legal points with the scribes of his day. Jesus was crucified because he was seen as a threat to the powers-that-be. His brand of non-violent resistance, his manner of stirring the people and empowering the poor, were correctly judged to be challenging the political power structures of his day.

None of this is to suggest that Jesus was a political rebel (a zealot), but it is to state that his mission of proclaiming the reign of God had profound political implications. Such implications became more evident in view of Jesus' actions in 'the cleansing of the temple'. Now the temple was not just a place. The temple was the symbol of the entire Jewish faith and its religious authority structure. Significantly, in two passion narratives the charge is brought against Jesus that he 'threatened' the temple. In effect, what is being stated is that his teachings and actions were threatening the very basis of Jewish life. Although the gospel-writers refute this claim, there is evidence to suggest that in both subtle and profound ways, Jesus certainly did challenge some of the central practices and institutions of Jewish life.

This radical challenge to Judaism could be described in terms of bringing about a new nearness of God to people which would have the effect of eliminating--at least significantly decreasing--the need for human mediators. Jesus' mission very clearly implied the right of everyone to address God as 'Father'. This meant that the Jewish leaders, especially the chief priests and sadduccees mentioned in the passion stories, had good reason to suspect that Jesus' radicalized religion did threaten their own roles and status.

A couple of things can be said about the charges brought against Jesus by the Jewish sanhedrin. First, they imply that Jesus' mission was not altogether a failure. Significant numbers of people, including some from the Jewish ruling classes, had come to a point of accepting that Jesus was indeed a true prophet, perhaps even the Messiah for whom Israel had been waiting. Second, this achievement was a very real threat to the status of lawful authority. If Jesus was seen as 'Christ' and 'Lord' to some, this very fact threatened the familiar lordship of others, notably the chief priests and scribes. Consequently, Jesus was a problem to the Jewish hierarchy from both religious and political perspectives.

However, none of this explains the involvement of Pilate and the Roman authorities. Despite the trumped-up charge of blashpemy that is brought against Jesus, it is important to recognize that he was sentenced to death by the Romans on the charge of political treason: "He claimed to be King of the Jews". This messianic title had very clear political implications. Luke's gospel expands on this charge: "We found this man perverting our nation, and forbidding us to give tribute to Caesar, and saying that he himself is Christ, a king" (23:1). The point here is that, to the Roman occupiers of Israel, Jesus could well have been perceived as a would-be revolutionary. At the very least, Pilate and the Roman authorities had good reasons to put a stop to the Jesus-movement on the basis of its subversive possibilities.

Although there are many unknowns with regard to the events surrounding Jesus' death, we can surmise that there was a deal struck between the Jewish leaders and the Roman authorities. Both had a stake in eliminating Jesus' brand of religon: the Jewish leaders had power and status to protect; the Romans were more concerned with law and order.

It is generally recognized that the gospel narratives place most of the responsibility for Jesus' death on the Jews rather than the Romans. At best, this is unbalanced reporting. At worst, it suggests an anti-semitic bias in early christianity. To put the record straight, Jesus did die at the hands of the Romans and in the manner of a Roman execution (the Jews did not have power to crucify). Nonetheless, it is impossible to construct an account of Jesus' trial and crucifixion that does not implicate the Jewish leaders of the day. All this points to the intimate connection between religion and politics in the Jewish society of Jesus' time.

The crucifixion and death of Jesus should always be seen in context of his life and ministry. Although Jesus was not concerned with establishing a political kingdom, his teachings on God's reign were deeply challenging of traditional Jewish institutions and practices. Jesus took a dangerous path: he attacked power and wealth; he overturned social attitudes that oppressed 'unclean' or 'unworthy' people; he taught the need for prayer and self-sacrificing service; he called people to freedom and empowerment in the face of injustice; he named the religious elite a 'breed of vipers' for its manner of sponging off the poor and the needy. In other words, Jesus made enemies among the Jewish leaders and their Roman overlords. These wealthy and powerful elite came to be threatened to the point that they needed to do away with him.

Jesus' approach to his death What then can we say about Jesus' own understanding of his approaching death? Since the crucifixion and death of Jesus were the result of his life and ministry, we can rightly assume that he must have reckoned with the possibility of death well prior to the end of his ministry. Jesus was neither a blind fanatic nor a fool. He was aware of the beheading of John the Baptist and he knew of the tragic fates of many prophets before him. Also, many of the charges levelled against Jesus--casting out demons in the name of Beelzebub, being a false prophet, breaking the sabbath, the accusation of blasphemy--were traditionally punishable through death by stoning.

Consequently, there can be no doubt that Jesus' journey to Jerusalem was the result of a deliberate and conscious decision to face danger including the danger of death itself. He knew of the growing opposition to him and his mission. Yet, despite this, he chose to make the trip to Jerusalem at the time of the Passover, a time when huge masses of people would be gathered in the city.

Why would Jesus make such a dangerous choice? The decision to go to Jerusalem marks the end of Jesus' Galilean ministry. It acts as a symbolic gesture of his explicit refusal to accept the way of a political messiah. In spite of this, the disciples still pin their hopes on a worldly kingdom. Jesus' frustration with their blindness becomes a recurring theme in the gospel narratives of the Jerusalem journey. People may hail him as a wonder-worker, king or messiah, but they still fail to comprehend his real message and mission.

Jesus discerns that his mission of proclaiming God's reign on earth will not be achieved through more of the same. Different strategies are needed. We see that Jesus becomes more confrontational in his approach (the temple scene); the radical edge to his teaching becomes more central. Jerusalem, the symbolic centre of Israel, was the logical place for Jesus to take his message. Perhaps Jesus thought that the religious capital would be more open to his teaching. His triumphant ride into Jerusalem suggests an initial enthusiasm--but, again, the people are disillusioned when they learn that Jesus does not intend to be a political messiah of their making.

In fact, the tide quickly turns. The hailed one becomes the decried one! There would still be opportunity for Jesus to retreat. However, by now he knew that a retreat from Jerusalem would be the retreat from his mission of proclaiming God's reign of love and mercy for all. In any case, he was too well known; there was little chance of hiding in the Galilean hills. And to take the escapist option of renouncing his mission was not a line of action that Jesus would countenance. So, in the face of an increasingly hostile opposition, Jesus grows to accept that the remote possibility of death has become an impending probability. Then the realisation dawns that there is no escape; death is certain.

Notwithstanding the violent death that Jesus was to undergo, he was also faced with the inevitable question of how to reconcile this impending reality with the message of God's love and salvation. How could the God of love allow such a painful and violent death? How could the reign of God be achieved through such evil and injustice? Jesus, who understood himself at least in terms of God's special envoy, could not have avoided facing such questions.

In assessing Jesus' response, we should be careful to avoid two extremes. First, we should distance ourselves from the approach that says that Jesus went to his death with feelings of despair and total abandonment by God. The words of the psalm attributed to Jesus on the Cross--"My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?"--, even if historical, need to be read in terms of the complete psalm which is, ultimately, a prayer of trust in God despite the evil that surrounds us. Jesus' whole life was lived in the belief of God's utter fidelity. Such belief would not abandon Jesus even in these most tragic circumstances of his bloody crucifixion.

Second, it is most important that we do not paint Jesus going to his death as a passive victim who was blindly fulfilling some pre-ordained divine plan. It is wrong to think that the human, historical Jesus had some kind of immediate access to God's will for him. Jesus made his life-decisions in the way that we all do: in the face of uncertainty and risk. He prays that he will come to know the Father's will and make the right decisions in view of his prayer and discernment. Aware of the risks, Jesus had made the crucial decision to take his mission to the heart of Judaism. Now he knows he must live with the consequences of that decision, including death itself.

The events surrounding the last supper and the agony in the garden are recorded in such a way to show that Jesus went to his death freely and deliberately--not because he actively chose death itself, but because he continued to commit himself to the mission of the kingdom in the face of opposition and evil. The act of the cup and bread at the 'last supper' symbolises the totality of Jesus' life, a life lived in loving service of others. Now Jesus is challenged to integrate the failure of his mission and his impending death into his life of 'service in love'. In other words, Jesus' death was marked by the same attitude that constituted his entire life. Perhaps Jesus simply believed that the promises of God would be fulfilled despite his death and the apparent failure of his mission. Or it may be that Jesus saw in a veiled way that his death would be a 'ransom for many', that is, an event that God would use to bring about the kingdom-community of justice, love and peace.

Interpreting Jesus' death In the early Jesus-movement, the suffering and death of Jesus came to be interpreted in many different ways. For some, the death of Jesus was seen as a sign that he was the eschatological prophet-martyr. After all, the Jewish tradition is full of stories of in which the true prophets are killed. The fact that Jesus was killed shows that he is the true prophet-martyr, in fact, the definitive or eschatological figure. This interpretation did not ascribe any particular theological significance to Jesus' death. It is Jesus himself, his person and mission, that is the central focus. Jesus' death merely shows that he is the one who is the 'true light of the world'.

Another interpretation focussed on the suffering of Jesus as an indication that he was the 'righteous one', the suffering Son of Man. Before prophets are killed, they are rejected and despised. Here there is a tendency to see suffering as the hallmark of God's endorsement of the true prophet. Consequently, Jesus' suffering is read in accordance with the divine plan of salvation. However, within this approach, the death of Jesus does not figure with any degree of prominence and is not, in itself, theologically important.

A third approach, however, did focus primarily on Jesus' death as a redemptive and atoning act. This is summarized in the Pauline formula which states that Jesus 'died for us on account of our sins' (Romans 4:25). The understanding developed that Jesus' suffering and death were 'saving realities'. This meant that the focus of attention moved from the person and mission of Jesus to the cross as an 'atoning sacrifice'. From this there develops a theology of salvation that is centred on the crucifixion and which reads the cross as a positive act of God which 'expiated the sins of the world'.

These various interpretations of Jesus' death witness to the struggle to make meaning out of the act of evil that brought Jesus' earthly life and mission to such an abrupt and cruel end. However we make sense of this human tragedy, it is imperative that we do see it first and foremost as a tragedy. Then, of course, we may well recognise that God can and does overturn evil and convert it into good. This is what came to be called in the Christian tradition the 'law of the cross'. Nonetheless, God does not condone evil, let alone require it in order to fulfill the divine plan of salvation. The suffering and death of Jesus, along with all other instances of violence and murder, are ultimately outside the powers of rational explanation. The most we can do is to acknowledge in faith that the mystery of God's love is finally more powerful than evil and death. Jesus' death, too, needs to be recognised in this light.

CHAPTER THREE Back to Christology Home Page CHAPTER FIVE