|

|

|

Jesus of the Gospels

The stories of Jesus of Nazareth recorded in the Gospels are attributed

to four disciples: Mark, Matthew, Luke and John. Without these sources, we

would know little about the historical Jesus. Yet, the Gospels are not biographies

or history in the strict sense of the word. They are faith documents witnessing

to Christian belief in Jesus as Son of God. Although based on eye-witness

accounts of Jesus, the Gospels combine facts with faith, history with theology,

events with interpretation. They each provide a different portrait of Jesus

that is more a work of art than historical scholarship. Written some thirty

to sixty years after Jesus' death, the Gospels rely on an oral tradition in

which stories were transmitted from one community to another. Their concern

was not historical accuracy but proclamation of the wonders God had done in

Jesus.

The stories of Jesus of Nazareth recorded in the Gospels are attributed

to four disciples: Mark, Matthew, Luke and John. Without these sources, we

would know little about the historical Jesus. Yet, the Gospels are not biographies

or history in the strict sense of the word. They are faith documents witnessing

to Christian belief in Jesus as Son of God. Although based on eye-witness

accounts of Jesus, the Gospels combine facts with faith, history with theology,

events with interpretation. They each provide a different portrait of Jesus

that is more a work of art than historical scholarship. Written some thirty

to sixty years after Jesus' death, the Gospels rely on an oral tradition in

which stories were transmitted from one community to another. Their concern

was not historical accuracy but proclamation of the wonders God had done in

Jesus.

This is why biblical scholars distinguish the Jesus of the Gospels from the Jesus of history. Certainly, there is relationship between the two, but each Gospel develops a particular portrait of Jesus according to its own set of memories and understandings. In reality, we can speak of four Gospel portraits of Jesus that arise from different experiences and concerns in the early Christian communities. Each portrait highlights diverse facets, accounts and interpretations of the historical Jesus without attempting to provide an accurate or detailed biography. Another way of describing this is to state that early Christian faith was already pluralistic in its expressions according to time, culture and emphasis.

Despite this pluralism, what is remarkable with regard to the recorded parables and miracles of Jesus is their fundamental consistency. In all four Gospels, Jesus is presented as one who teaches in parables and performs miraculous deeds. Without the parables and miracles, the public ministry of Jesus would make for slim reading indeed. How then are we to interpret these central events in the public life and ministry of Jesus? Before answering this question, we need to understand something of the modern quest for the historical Jesus and the current state of biblical scholarship in "Jesus Studies."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Old Quest: Nineteenth Century

Interest in discovering the historical

Jesus became a fascination for scholars in the late eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries. Until then, little critical attention was given to the Gospels

as historical documents. This changed with the publication of Fragments

by a German scholar named Reimarus who argued that Jesus was a revolutionary

who attempted to set up a new political kingdom on earth. Jesus' evident failure

to achieve his goal resulted in the second move: the followers of Jesus stole

the body and made up stories about Jesus' miracles and resurrection in order

to keep the dream going. The Christian Church was nothing else than an elaborate

fraud!

Interest in discovering the historical

Jesus became a fascination for scholars in the late eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries. Until then, little critical attention was given to the Gospels

as historical documents. This changed with the publication of Fragments

by a German scholar named Reimarus who argued that Jesus was a revolutionary

who attempted to set up a new political kingdom on earth. Jesus' evident failure

to achieve his goal resulted in the second move: the followers of Jesus stole

the body and made up stories about Jesus' miracles and resurrection in order

to keep the dream going. The Christian Church was nothing else than an elaborate

fraud!

Reactions to Reimarus' "repulsive caricature" of Jesus were passionate. Two Christian factions emerged: the supernaturalists and the rationalists. The supernaturalists adopted a literal view of Scripture. They saw no discrepancy between the Jesus of the Gospels and the Jesus of history: each parable was faithfully reported just as if someone was there to record Jesus on tape; each miracle occurred precisely in the way the Gospels recorded it. They simply ignored the many evident discrepancies among the Gospel accounts of Jesus and discredited historical scholarship.

In contrast, the rationalists rewrote the history of Jesus according to nineteenth century liberal views. By stripping away the early church's teaching, they believed they could arrive at an acceptable picture of Jesus as he really was. They worked mainly with Mark's Gospel since it was the earliest and, so they thought, the most historical. Jesus' miracles were explained in terms of parapsychology or other 'natural' causes. The 'miracle' of the loaves and fishes occurred through Jesus setting a good example of sharing his food with others. Stories of raising the dead can be explained in terms of people being buried alive. The historical Jesus in this scenario is little more than a gifted ethical teacher and social worker.

Between these two extremes are a number of scholars whose contribution to the debate has proven more valuable. J. Weiss is significant in arguing that Jesus needed to be understood as a first century Palestinian Jew. In this regard, Jesus' preaching on the reign of God shared the Jewish apocalyptic expectation of the end of the world. Second, Weiss argued, Jesus believed he had a particular mission to announce its coming. If Jesus healed and cast out demons, as the Scriptures testify, this signified for Jesus the final and immanent conflict in which God would triumph over the power of evil.

Another

scholar, Wrede, is famous for his thesis on the "messianic secret"

in Mark's Gospel. He asks why Mark's Jesus consistently tells his disciples

not to tell anyone he is the Messiah. Wrede suggests this tells us more about

Mark's community than it does about Jesus. Struggling to come to terms with

the Jewish rejection of Jesus, the Christian  community is provided with an explanation

imputed to the words and actions of Jesus himself. However, this is nothing

other than a "literary device" invented by the author, Mark. Whatever

else this says, it certainly challenged the accepted liberal view of the day

by arguing that, no less than the other Gospels, Mark's account of Jesus'

life and mission is highly theological.

community is provided with an explanation

imputed to the words and actions of Jesus himself. However, this is nothing

other than a "literary device" invented by the author, Mark. Whatever

else this says, it certainly challenged the accepted liberal view of the day

by arguing that, no less than the other Gospels, Mark's account of Jesus'

life and mission is highly theological.

The nineteenth century quest for the historical Jesus came to an abrupt conclusion with the 1906 publication of Schweitzer's The Quest of the Historical Jesus. Schweitzer demonstrated first and foremost that little progress had been made. Neither the supernaturalists nor the rationalists were convincing. Schweitzer develops Wrede's thesis arguing for the impossibility of getting behind the Gospels to recover the real Jesus of history. In the end, he too settles for an apocalyptic Jesus who was a well-meaning, heroic but ultimately deluded preacher of the last days. The search for the historical Jesus seemed to have come full circle without achieving any degree of resolution. Scholarship in the field halted for nearly half a century.

Bultmann and The New Quest

In the 1940s, German Lutheran theologian

Rudolf Bultmann

declared the quest for the historical Jesus was, for all intents and purposes,

impossible. Accepting Wrede's thesis that the Gospels are impregnated with

early Church beliefs, Bultmann does not see how we can get behind them to

the historical Jesus. Moreover, he does not see this as a concern for Christian

faith. The Gospels are myths. What is important is the message at the heart

of the Gospels conveyed through the power of the Word. Our task today is to

'de-mythologise' the language of the Gospels to hear the message anew. For

Bultmann, it is enough for Christians to know the historical Jesus existed.

In the 1940s, German Lutheran theologian

Rudolf Bultmann

declared the quest for the historical Jesus was, for all intents and purposes,

impossible. Accepting Wrede's thesis that the Gospels are impregnated with

early Church beliefs, Bultmann does not see how we can get behind them to

the historical Jesus. Moreover, he does not see this as a concern for Christian

faith. The Gospels are myths. What is important is the message at the heart

of the Gospels conveyed through the power of the Word. Our task today is to

'de-mythologise' the language of the Gospels to hear the message anew. For

Bultmann, it is enough for Christians to know the historical Jesus existed.

Others disagreed. Käsemann, a former student of Bultmann, proposed that the search for the historical Jesus was legitimate, necessary and possible. Legitimate because the evangelists point people to the historical Jesus. Necessary because if Christianity is centred purely on a Christ of faith it will be dismissed as just another humanly constructed myth. Possible because new methods of historical enquiry enable scholars to distinguish Gospel sources (source criticism), identify literary and theological statements (form criticism) and recognise editing processes (redaction criticism) in the writing of the Gospels. The Old Quest had failed only because these newer methods of historical research were unavailable.

It must also be stated that the New Quest for the historical Jesus is much less ambitious. There is no presumption that historical scholarship can either prove or disprove Christian faith. At most, it establishes some continuity between the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith. The approach is more critical and realistic. Scholars know that advances in human knowledge are inevitably partial and open to ongoing critique. With these more humble goals, the Jesus debate has achieved some degree of agreement: Jesus of Nazareth was a first century Palestinian Jew; the message of "God's reign" was at the heart of his life and ministry; he was variously understood as prophet, miracle-worker, speaker of parables, advocate for the poor and marginalised; his crucifixion resulted from his being perceived a threat to the Jewish and Roman leaders of his day.

The New Quest recognises certain patterns in the public ministry of Jesus--even if these patterns are interpreted differently by scholars. Some perceive Jesus primarily in social and political terms such as peasant sage or social revolutionary. Others see the dominant key for interpreting Jesus in theological terms such as religious mystic, true messiah or eschatological prophet. All agree that for a proper understanding of the historical Jesus, we cannot divide the social, political and religious dimensions of culture for first century Judaism in the way we might for twenty-first century Australia. Perhaps Jesus was all these things and more, as Christian faith will assert. For the moment, we restrict ourselves to the domain of historical scholarship.

The most notable area of debate concerns

the understanding of the God's reign in Jesus' ministry. Was Jesus predicting

some kind of future divine intervention, or did he understand the reign of

God as a reality in the present? A few scholars, following Weiss and Schweitzer,

perceive Jesus as a purely apocalyptic prophet misreading the end-time as

an immanent but future event (Sanders). On the other extreme are members of

the Chicago-based Jesus Seminar who reject the authenticity of texts

which speak of the coming Son of Man and future judgment (Crossan). For them,

Jesus understands the reign of God as a purely present reality. However, most

scholars understand the reign of God as a "tensive metaphor" referring

to both a future other-worldly event and a present-day reality

associated with Jesus' own ministry. This position is convincingly argued

by John Meier in his seminal work A Marginal Jew and forms

the basis of our approach to Jesus' parables and miracles throughout this

chapter.

The most notable area of debate concerns

the understanding of the God's reign in Jesus' ministry. Was Jesus predicting

some kind of future divine intervention, or did he understand the reign of

God as a reality in the present? A few scholars, following Weiss and Schweitzer,

perceive Jesus as a purely apocalyptic prophet misreading the end-time as

an immanent but future event (Sanders). On the other extreme are members of

the Chicago-based Jesus Seminar who reject the authenticity of texts

which speak of the coming Son of Man and future judgment (Crossan). For them,

Jesus understands the reign of God as a purely present reality. However, most

scholars understand the reign of God as a "tensive metaphor" referring

to both a future other-worldly event and a present-day reality

associated with Jesus' own ministry. This position is convincingly argued

by John Meier in his seminal work A Marginal Jew and forms

the basis of our approach to Jesus' parables and miracles throughout this

chapter.

Key Themes Used By Scholars to Interpret the Historical Jesus

|

Peasant Sage |

Social Revolutionary |

Religious Mystic |

Marginal Jew |

Apocalyptic Prophet |

Eschatological Prophet |

True Messiah |

|

Jesus Seminar |

Dominic Crossan |

Marcus Borg |

John Meier |

E. P. Sanders |

Edward Schillebeeckx |

N. T. Wright |

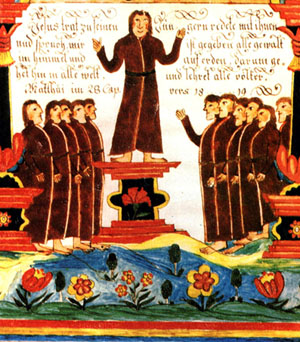

Jesus Teacher and Prophet

Few scholars

question the historical authenticity of Jesus' parables and radical sayings.

They point to the originality of Jesus as teacher and prophet. Whereas a typical

'rabbi' (Jewish word for 'teacher') taught in synagogues, Jesus teaches

mainly in the countryside, near a lake, on a mountain or in the open fields.

He directs his teachings to ordinary people including the sick, women, children

and even foreigners. He uses everyday experiences or images from nature: meals

and journeys, sheep and goats, coins and pearls, wheat and darnel, cloth and

oil lamps, trees and birds. Jesus teaches fidelity to the Scriptures while

being opposed to legalistic interpretations of fasting, ritual purity and

the Sabbath. On  other matters, such as divorce, Jesus

appears to take a strong stand that upholds traditional teaching. He does

not oppose the right of the State to conduct its affairs, but he challenges

corrupt practices that place unjust burdens on people's backs.

other matters, such as divorce, Jesus

appears to take a strong stand that upholds traditional teaching. He does

not oppose the right of the State to conduct its affairs, but he challenges

corrupt practices that place unjust burdens on people's backs.

In all four Gospels, the beginning of Jesus' public ministry is associated with John the Baptist. Like John, Jesus teaches the importance of faith and repentance. Like Hillel, another prophet of the time, Jesus emphasises God's mercy and compassion. He departs from accepted practice by choosing his own disciples and enjoying table-fellowship with tax-collectors, prostitutes and sinners. The ease of his relationship with women also raises eyebrows. Above all, the historical Jesus emerges as one who speaks and acts with great personal authority by ministering to social outcasts, claiming to forgive sins and speaking of his own relationship with God in the most intimate terms ("Abba-Father"). Sociologists tell us that Jesus' ministry can be likened to that of the "ethical prophet" who critiques the unjust sufferings of marginal groups and plays a significant role in redefining the tradition. In particular, Jesus redefines the image of God's reign and its import for the Jewish people and society of his day.

The Reign of God

The notion of God's reign/kingdom was central enough to Jewish ears at the time of Jesus. According to the Jewish Scriptures, the whole creation was subject to its creator, lord and king, Yahweh. Moreover, God's reign extends over the events of Israel's history nowhere more evident than in the story of the Exodus in which the Israelites are led from slavery to freedom. Israel itself eventually became a monarchy under its favourite kings, Solomon and David. However, unlike their neighbours, Israel did not divinise their kings who always remained subject to Yahweh, the God of Israel. When the kingdom dissolved through internal division and external forces, the people held onto their belief in Yahweh. Israel's prophets provided a new vision in which Yahweh had a plan not just for Israel, but for the whole of human history. Despite Israel's infidelities and enslavement, Yahweh would create a new heaven and a new earth. Israel lived in the hope that Yahweh, their king, would restore their monarchy (on earth) and provide a future for all creation (in heaven).

So, when Jesus spoke of the kingdom of God, his hearers were able to relate this to a rich tradition. The reign of God had something to do with fulfilling Israel's dreams as a nation and overcoming the forces of evil. Israel, though, was a nation on its knees. By the time of Jesus, many Jews had abandoned the hope of a restored monarchy and began to interpret the reign of God in terms of apocalyptic destruction. Those who held onto the notion of a political restoration of the monarchy became increasingly committed to the strategy of armed revolution. One way or other, the coming reign of God was associated in people's minds with some kind of violence. The novel aspect of Jesus' teaching was that the coming of God's reign was not associated with violence (apocalyptic or revolutionary) but with its opposite--love. Moreover, it was not just a future event (something all Jews believed). Jesus also taught that the reign of God is already here and happening now.

Consequently, Jesus' teaching on the reign of God found a ready audience. It is also understandable that, after initial enthusiasm, people became suspicious of this new vision. How, they asked, did Jesus arrive at his peculiar way of interpreting this central idea of Jewish faith? And, on what authority did he base it? What may have seemed authentic to his more faithful followers appeared as nothing less than arrogance to his growing number of enemies. Jesus relates his understanding of the kingdom to his personal religious experience of intimacy with God as Abba-Father. He even dares to speak in God's name as the accusation of blasphemy makes clear at his trial. At another level again, there would be sheer frustration in arriving at any clear notion of what Jesus intended by his ideas that must have appeared radical to some, reactionary to others, and confusing to most. In reality, people began to see that Jesus' ideas were subversive. This is nowhere better demonstrated than in a closer reading of some of his parables.

Why Parables?

In three Gospels, it is reported that the disciples asked Jesus

directly: "Why do you speak in parables?" He answers: "I speak

in parables so that they may look but not see, listen but not hear or understand"

(Mk.4:10-12). It is, however, highly unlikely that Jesus set out to be so

deliberately obfuscating. This tells us more about the early Christian communities

seeking to understand the reason for Jesus' rejection. It is a good example

of what Wrede calls the "messianic secret" in Mark's Gospel.

In three Gospels, it is reported that the disciples asked Jesus

directly: "Why do you speak in parables?" He answers: "I speak

in parables so that they may look but not see, listen but not hear or understand"

(Mk.4:10-12). It is, however, highly unlikely that Jesus set out to be so

deliberately obfuscating. This tells us more about the early Christian communities

seeking to understand the reason for Jesus' rejection. It is a good example

of what Wrede calls the "messianic secret" in Mark's Gospel.

So, then, are the parables moral example stories in which Jesus makes ethical points about how to live a good life? Luke's Jesus does precisely this when, at the conclusion to his parable of the Good Samaritan (10:29-37), he tells his listeners: "Go and do likewise." That is, treat other human beings as your neighbour in line with the admonition that we should love our neighbour as ourselves. Love is reflected in actions, and the loving actions of the Samaritan, unlike the selfishness of the priest and the Levite, are to be imitated.

There is another interpretation of this same parable by St. Augustine in the fifth century. Augustine treats the parable as an allegory in which each part of the story represents an aspect of salvation history: the priest and Levite represent the Old Law; the Samaritan is Jesus Christ; the oil and wine, the Christian sacraments; the inn is Mother Church which cares for the soul until the Lord's second coming. Such allegorical interpretations are also evident in the Scriptures themselves. For example, after telling the parable of the Sower (Mk.4:1-9), Jesus follows up with an explanation of its meaning (Mk.4:13-20): the seed is the Word of God; the places the seed lands--path, rocky ground, thorns, good soil--represent the different responses people make to hearing the Word.

Without rejecting the value of moral and allegorical interpretations, modern scholarship (notably Dodd and Jeremias) has focussed attention on the organic unity and underlying structure of parables. It also asks how parables function in relation to the central message of the reign of God in Jesus' teaching and ministry. Building on this approach, contemporary scholars (notably Funk and Crossan) point to the event-like character of parables in which Jesus challenges his hearers to a new mode of being in the world. He does not simply talk about the reign of God but seeks to give the listener an anticipatory experience of what the reign of God is like in the here and now. Parables play on the relationship between the familiar and the strange; they reverse our ordinary way of experiencing the world and shock us into a type of reversed consciousness. Parables induce us to look at our lives and make a decision about our futures.

Interpreting Parables

|

|

|

Reinterpreting Parables

Viewed

in this light, the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Pharisee and the

Publican (Lk.18:9-14) are deeply subversive. Jewish people in Jesus' day had

clear ideas about virtue and prayer: priests and Levites are virtuous; God

hears the prayers of good people such as Pharisees. What we find, however,

is that Jesus reverses the plots: it is the low-class Samaritan foreigner

who is virtuous; God hears the prayer of the publican sinner. More shocking

still: the actions of the 'holy' priest and Levite are sinful; the prayer

of the 'virtuous' Pharisee is unsuccessful. Evidently, the initial hearers

of these parables are shocked. It is understandable that even members of Jesus'

own family began to think he was mad. The parables force their hearers into

making a decision about Jesus and about themselves.

Viewed

in this light, the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Pharisee and the

Publican (Lk.18:9-14) are deeply subversive. Jewish people in Jesus' day had

clear ideas about virtue and prayer: priests and Levites are virtuous; God

hears the prayers of good people such as Pharisees. What we find, however,

is that Jesus reverses the plots: it is the low-class Samaritan foreigner

who is virtuous; God hears the prayer of the publican sinner. More shocking

still: the actions of the 'holy' priest and Levite are sinful; the prayer

of the 'virtuous' Pharisee is unsuccessful. Evidently, the initial hearers

of these parables are shocked. It is understandable that even members of Jesus'

own family began to think he was mad. The parables force their hearers into

making a decision about Jesus and about themselves.

The parables of Jesus take this unexpected turn and, in so doing, reinforce the way Jesus performs his ministry, mixes with women, talks to foreigners and eats with outcasts. So when, for example, Jesus tells the parable of the Great Banquet (Lk.14:15-24) in which all the outsiders are welcomed to the meal at the expense of the invited guests, this resembles the kind of table-fellowship that Jesus himself practices. The confrontation is double: not only are Jesus' actions a notable reversal of the accepted conventions of his day; he is now suggesting through word and parable that only those who act this way are worthy of the reign of God.

The parables

often play out this tension between inclusion and exclusion at banquets--and

to many in the audience it must have become evident that Jesus was advocating

a kingdom of no-hopers. Take for example the Prodigal Son (Mtt.18:21-35) who,

after a life of debauchery, is rewarded with the biggest feast imaginable.

The elder brother--by all accounts a model son who stays home and works the

farm--is understandably outraged. No party has been thrown on his account!

All this is deeply disturbing and seems to portray a God whose sense of justice

and fairness is entirely out of whack. Others in the audience may have responded

with new insight into the mercy and compassion of God thereby overturning

narrow or legalistic conceptions of divine justice. Nobody could hear this

parable and remain quite the same.

The parables

often play out this tension between inclusion and exclusion at banquets--and

to many in the audience it must have become evident that Jesus was advocating

a kingdom of no-hopers. Take for example the Prodigal Son (Mtt.18:21-35) who,

after a life of debauchery, is rewarded with the biggest feast imaginable.

The elder brother--by all accounts a model son who stays home and works the

farm--is understandably outraged. No party has been thrown on his account!

All this is deeply disturbing and seems to portray a God whose sense of justice

and fairness is entirely out of whack. Others in the audience may have responded

with new insight into the mercy and compassion of God thereby overturning

narrow or legalistic conceptions of divine justice. Nobody could hear this

parable and remain quite the same.

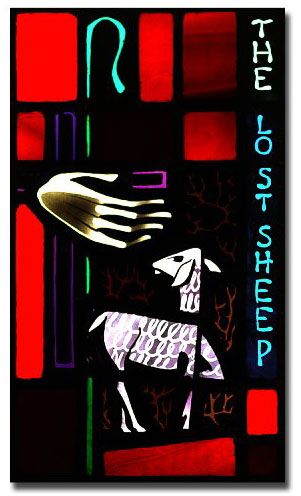

Then there are the Lost and Found parables (sheep, pearls, coins) [Mtt.13:44-46; 18:10-14]. At one level, these are earthy, common-sense stories that draw the hearer into a familiar and plausible situation. What we then notice is the way the details become vivid, distorted, exaggerated. For example, leaving a flock of ninety-nine hapless sheep to fend for themselves would not be countenanced by any guild of shepherds. However, the shepherd in Jesus' story does precisely this. Who, then, is this reckless shepherd? The searcher for the kingdom? Or is it God who is reckless in searching for us? This is where the open-ended meaning of parables becomes evident. There is no single interpretation. Jesus leaves it to his listeners to decide.

Jesus' parables are all about shattering accepted social values, moral attitudes, common behaviours, religious practices and human prejudices. When this occurs, the reign of God is given space to grow as in the parables of the Mustard Seed or the Yeast (Mtt.13:31-33). Jesus' radical sayings function in a similar manner. They jolt the hearer into making a response. Evidently, the reign of God is closely allied to people changing their vision of what it is to be human. Some find all this too much and, as predicted in the story of the rich young man, walk sadly away. To hear the message of the parables and radical sayings is to experience something of God's kingship in the world of the here-and-now--and to change accordingly.

|

|

|

Leave the dead to bury their own dead. (Lk.9:60) If anyone strikes you on the right cheek, let him strike you on the left cheek as well. (Mtt.5:39) Whoever tries to save his life will lose it; but whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel will save it (Mk.8:35) It is easier for a camel to pass through an eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven (Mk.10:23) The first will be last; and the last will be first (Mk.10:31) Unless you become like a little child, you will never enter the kingdom of God (Mk.10:15) Love your enemies; do good to those who hate you; bless those who curse you; pray for those who abuse you (Lk.6:27-28) |

Science and Miracles

We have said that Jesus' teaching on the reign of God was related to Israel's hopes of fulfilment and to answering the problem of evil. Yet, if Jesus merely challenged people with strange stories and confronting sayings, he would be easily dismissed as just another religious nutter. Jesus not only spoke about the kingdom, he reinforced his message through what came to be described as wondrous deeds and miraculous events. To modern ears, influenced by scientific understandings of causality and the laws of nature, Jesus' miracle stories are met with understandable scepticism. And yet, contemporary secular culture greets stories of the paranormal with an increased degree of interest. Science itself with its array of new explanations of cosmic processes (relativity, quantum, chaos and parallel universe theories, to name four) seems more rather than less open to the dimension of mystery at the heart of our universe. The old rationalist rejection of the miraculous is no longer on such sure ground.

Still, the contemporary mindset remains more than a little bemused at the miraculous events attributed to Jesus. Again, we are forced to ask two questions: one historical, the other modern. How did the Jewish people of Jesus' day understand his miracles? And, did they actually happen? In answer to the second question, there is much we cannot know. What we can say with certainty is that many people believed Jesus was indeed a worker of miracles. Yet, even here, biblical scholars disagree with regard to which reported miracles were considered historical during Jesus' earthly life and to what degree they have been redacted by post-Resurrection belief in Jesus as Christ, Lord and Saviour. To answer the modern question of "what actually happened?" we need first to answer the historical question of how first century Jewish people understood miracles in their own time, place and culture.

Miracles in Judaism

Miracles, in fact, do not play a major role in the tradition of Israel. Exceptions to this are miraculous signs and events associated with Moses at the time of the Exodus, with the prophets Elijah and Elisha in the Book of Kings, and with accounts in the Book of Daniel. There are very few stories of healings and resuscitations. Certainly, there is nothing in the Hebrew Scriptures to compare with the miracle performances attributed to Jesus in the Gospels.

A few scholars argue that Jesus fits more neatly into the tradition of the magician or sorcerer. However, this parallel does not work well. Magicians did not see themselves as proclaiming a religious mission. Their goals were narrower. They worked secretively, using magical formulae and claiming to be adept at manipulating spirits. As well, the magician claimed to possess divine powers and did not refrain from overpowering the will of the person on whom the magic was being induced. In contrast, Jesus' miracles usually occur in public places; there is no magical formula; they are performed in the name of God rather than Jesus himself; they do not require the submission of the person's will but faith in the healing power of God. Nor, as we shall see, did Jesus claim to possess divine powers.

Nonetheless, for the Jewish mind, the question of the possibility of miracles was not in question. After all, Yahweh was the lord of creation and king of history: they reasoned that God could do whatever God liked. Cosmic and historical processes were not interpreted according to laws of nature: things happened either through God's power or the power of Satan. Not that human influence was discounted. Sickness, for example, was associated with the power of demons or with the evil committed by oneself or one's forebears. Such interpretations resulted in a high degree of social stigma and rejection experienced by those who suffered any form of physical disability or mental illness. Interestingly, the question of Jesus' ability to heal people and perform other wondrous signs was never in question. What was questioned was whether Jesus' miracles were due to God or the devil. The religious elites of Jesus' day were more inclined to the second opinion.

Historicity of Miracles

Consequently, we approach the question of the historicity of the miracles with a very different set of concerns. The modern question, as we have called it, focuses on accuracy of detail and natural causes. If something is verified as true, we want to know how it is explained. An unfortunate element of most modern approaches to the question has been the simple--indeed simplistic--division between the natural and the supernatural. Christian theology throughout the twentieth century has gone a long way towards discarding such an unhealthy dichotomy. Theologians Henri de Lubac and Karl Rahner provide foundations for appreciating a more dynamic and complex interrelation between grace and nature, God and the world. Still, the popular imagination remains tied to explaining causation in terms of God or science. According to this scenario, God is or can be the explanation only for those things science cannot explain. However, what if God works in and through natural and cosmic processes?

The miracles attributed to Jesus are inexplicable,

and will be logically dismissed of credibility, without this more refined

worldview. In other words, the very notion of miracle needs redefinition.

Rather than focus on causes, the newer definition is concerned with the religious

significance attributed to remarkable events or deeds. Take for example the

healing stories of Jesus. If such events occurred, they demonstrated out-of-the-ordinary

powers. A religious explanation will state that God's power is evident in

the healings. If it can be further demonstrated that some natural cause is

at work in the process this does not, in itself, dismiss the remarkable nature

and religious relevance of the cures. However, that is a response of religious

faith that goes beyond scientific hypotheses and empirical data. Non-believers

will find this explanation unconvincing. Yet, for religious believers, all

the scientific explanations of the origins of the universe at the Big Bang

only serve to increase rather than diminish their faith in the miracle of

God's creation.

The miracles attributed to Jesus are inexplicable,

and will be logically dismissed of credibility, without this more refined

worldview. In other words, the very notion of miracle needs redefinition.

Rather than focus on causes, the newer definition is concerned with the religious

significance attributed to remarkable events or deeds. Take for example the

healing stories of Jesus. If such events occurred, they demonstrated out-of-the-ordinary

powers. A religious explanation will state that God's power is evident in

the healings. If it can be further demonstrated that some natural cause is

at work in the process this does not, in itself, dismiss the remarkable nature

and religious relevance of the cures. However, that is a response of religious

faith that goes beyond scientific hypotheses and empirical data. Non-believers

will find this explanation unconvincing. Yet, for religious believers, all

the scientific explanations of the origins of the universe at the Big Bang

only serve to increase rather than diminish their faith in the miracle of

God's creation.

It may seem that this has not taken us very far with regard to establishing the historicity of particular miracle-stories of Jesus. We know that Jesus is acclaimed as one who heals the blind, lame, lepers and the deaf; he casts out demons, raises the dead to life, calms the seas, walks on water and changes water into wine. We also know that the Gospel accounts do not pretend to historical accuracy: they reflect the faith of the early Church in Jesus who has power over death itself. This is to say that some serious editing has transformed original events into magnified versions of those events. By the time the Gospels are being written, few if any eyewitnesses are present to authenticate historical detail. Can we go further than this in our task of verifying the miracle-stories?

Many scholars suggest we can. They divide miracles into various categories: healings and exorcisms; raising from the dead; nature miracles. Generally, it is accepted there is high historical probability that Jesus did indeed heal and exorcise people. Among reasons for this judgment is the fact that the healings and exorcisms are from the earliest strata of the Jesus tradition. Second, they are unique, numerous and central to all Gospel portraits of Jesus. Third, opponents of Jesus do not deny his healing powers--they simply attribute those powers to other causes including, in one case, "the power of Beelzebul, the prince of demons" (Mk.3:22). Fourth, the ministry of Jesus' proclamation of God's reign is fully coherent with his role as healer and exorcist: the nearness of God's kingdom brings liberation from all kinds of oppression including sickness of body, mind and spirit.

Scholars are more reluctant to attribute historical probability to nature miracles which parallel stories from other traditions. They suggest these stories are most likely applied to Jesus as a way of indicating his special divine status. Stories of Jesus raising people from the dead also receive an unenthusiastic reception on historical grounds--although a scholar as significant as John Meier does leave the way open for the possible historicity of Jesus raising the daughter of Jairus (Mk.5:21-43). This miracle-story, as written, is relatively unadorned by the kind of theological overlay that expresses early Christian faith. The position on the historicity of miracles taken here does not pretend to do more than outline the major features of contemporary scholarship in the field. It affirms that Jesus was in some sense a miracle-worker even though the question of the historicity of particular miracle-events remains unresolved. Our final task is to examine the significance of Jesus the miracle-worker within the framework of his public life and ministry.

Miracles and Reign of God

People have sometimes used the miracles as proofs of Jesus' divine status. As understandable as this may be, we can be fairly certain nothing was further from the mind of Jesus himself. In the context of everything we know about Jesus' public life and ministry, there is nothing to suggest he ever performs miracles to bring attention to himself. In fact, the Gospels show Jesus refusing this kind of self-referential miracle (Mk.8:11-12). The referent of Jesus' actions is always God-Abba-Father whose coming reign Jesus proclaims through word and deed. When events are proclaimed miraculous they are, from Jesus' own perspective, nothing more and nothing less than indications that God's healing, saving and redeeming power is not merely a reality of past and future, but something available to people in the here-and-now.

This is where the parables and miracles complement each other. We have seen that parables are subversive stories shattering the self-enclosed worlds of the rich and powerful. God's kingdom arrives here to shock the accepted view of what is good and virtuous. Beyond those shattered worlds, Jesus' actions in curing people of disease point to another dimension of the reign of God that heals, liberates and saves. Luke's Jesus begins his public ministry by reciting the words of Isaiah: "The Spirit of the Lord has chosen me to bring good news to the poor, proclaim liberty to captives, give sight to the blind, and set the oppressed free" (4:18-19). In Jesus' time, and perhaps in our own, this message of God's preferential option for the poor and oppressed had been lost. The whole of Jesus' ministry challenges people to a new vision of a liberating, loving God who sides with the marginalised. His healings and exorcisms are metaphors or signs of the reality of such a God.

Miracles in Jesus' ministry are, then, best understood

as dynamic signs of the nearness of God's kingdom. They are not merely actions

of a compassionate social worker responding to people in need. There is, for

example, no suggestion that Jesus tries to heal everyone who suffers physical

disability and mental illness. In this sense we can say that Jesus' ministry

is an expression of a religious mission. It is God-centred. God is the answer

to people's hopes for fulfilment; God is the answer to the overcoming of evil.

What the miracles show in Jesus' ministry is that the God-answer is not a

matter of philosophical debate; it is a reality that can be already experienced

by those who believe in the reign of God. Although God's victory over suffering

and evil is far from complete, the miracles are signs of the coming victory.

They also challenge those who place their faith in political power, religious

laws or the Temple itself as the final answer to human happiness. For this

reason, Jesus' miracles also turn out to be politically subversive acts.

Miracles in Jesus' ministry are, then, best understood

as dynamic signs of the nearness of God's kingdom. They are not merely actions

of a compassionate social worker responding to people in need. There is, for

example, no suggestion that Jesus tries to heal everyone who suffers physical

disability and mental illness. In this sense we can say that Jesus' ministry

is an expression of a religious mission. It is God-centred. God is the answer

to people's hopes for fulfilment; God is the answer to the overcoming of evil.

What the miracles show in Jesus' ministry is that the God-answer is not a

matter of philosophical debate; it is a reality that can be already experienced

by those who believe in the reign of God. Although God's victory over suffering

and evil is far from complete, the miracles are signs of the coming victory.

They also challenge those who place their faith in political power, religious

laws or the Temple itself as the final answer to human happiness. For this

reason, Jesus' miracles also turn out to be politically subversive acts.

In the story of Jesus healing the man with a paralysed hand, there is direct confrontation with the religious elite. The issue at stake is the right of Jesus to heal on the Sabbath. A legalistic interpretation of Jewish law treated the Sabbath as ultimate. Although respecting the Law and the Sabbath, Jesus does not hesitate to relegate both to a lower level than the experience of God's reign and healing power. Matthew tells us that after Jesus healed the man, "the Pharisees left and made plans to kill Jesus" (12:14). The determination of Jewish leaders to kill Jesus reaches a climax after the Temple incident where Jesus does two things: he drives out the petty capitalists for misusing God's house; and he heals the blind and crippled who, against Jewish law, come to visit him in the Temple (Mtt.21:12-17). Jesus' healing miracles are, then, correctly interpreted as subversive acts threatening religious and political interests. They show that the powerful and wealthy had too much to lose if this message of God's liberating love for the poor and oppressed got out of hand.

In this sense, Jesus' miracles are not only signs of the kingdom; they also dramatise political aspects of his mission. Such an interpretation is misunderstood if it turns Jesus into a modern-day social revolutionary. Certainly, miracles empower certain people (mainly social outcasts) and subvert the power of others (mainly the establishment). However, what Jesus makes clear throughout his mission is that all power and authority belong to God; and that God alone is the answer to human fulfilment and the problem of evil. Jesus' teaching on the reign of God begins with the call to repent and believe. Whenever he reaches out to people with healing power, the question of faith in God's power to break into human lives and human history is paramount. At the conclusion of miracle-stories, Jesus often states: "Your faith has made you whole" (Mk.5:25-34). Elsewhere, it is maintained Jesus could not work many signs because people lacked faith (Mk.6:5). On other occasions, Jesus' miracle-actions are associated with the forgiveness of sins (Lk.5:17-26) or with the call to prayer and thanksgiving (Mk.5:19-20).

Miracles are central to Jesus' ministry on behalf of the kingdom. Their purpose is not to divinise Jesus, but to reveal the power of God at work in unexpected ways. They call people to conversion of heart, vision and action so that they too become signs of God's dynamic reign in the form of fully inclusive, healing, liberating community. As recorded in the Gospels, miracles show how the mystery of God's plan demands faith, forgiveness, prayer and thanksgiving. The miracles also reveal that God's reign touches every aspect of life including bodily healing, spiritual wholeness and overturning human prejudice and unjust social systems. Finally, beyond questions of historicity, miracle-stories of Jesus raising the dead and nature-miracles point to the early Church's belief that Jesus reveals a God who is also sovereign over death and the whole creation.

It is important to realise the New Quest for the historical Jesus is ongoing and will never achieve total consensus. Notwithstanding differences of interpretation, the emerging pattern accepted by all recognized scholars today is that Jesus of Nazareth was a teacher and prophet who understood himself and was understood by others with respect to the parameters of first century Judaism. Within that context, he probably shared the contemporary belief in the immanent arrival of the end-times. However, Jesus' public ministry reveals something more important, namely, that the coming reign of God is "good news" for those who can receive it. He spoke about this in his teachings and parables and symbolised its reality through his healings, exorcisms and other wondrous deeds.

Biblical scholarship can only take us so far. Nothing like a full-scale biography of Jesus is possible and much ambiguity remains. Nonetheless, for those who wish to understand his message, the parables and miracle-stories take us to the heart of the Gospel. They subvert our ordinary way of seeing the world and invite us to be vulnerable so that the miracle of God's reign will be experienced even now among us.

Borg, Marcus J. Jesus in Contemporary Scholarship. Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International, 1994.

Crossan, J. Dominic. The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991.

Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus. New York: Macmillan, 1993.

___________. The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998.

Gowler, David B. What are they saying about the Parables? New York: Paulist Press, 2000.

Jeremias, Joachim. New Testament Theology. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971.

Loewe, William P. The College Student's Introduction to Christology. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1996.

Luttenberger, Gerard H. An Introduction to Christology. Mystic, CT: Twenty-Third Publications, 1998.

Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. Vols. 1 & 2. New York: Doubleday, 1991 & 1994.

Perrin, Norman. Jesus and the Language of the Kingdom. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1976.

Powell, Mark. The Jesus Debate: Modern Historians Investigate the Life of Christ. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998.

Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. London: Penguin, 1993.

Schillebeeckx, Edward. Jesus: An Experiment in Christology. New York: Seabury Press, 1979.

Schweitzer, Albert. The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of the Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. Reprint. New York: Macmillan, 1968 [Original 1906].

Wright, N. T. Who Was Jesus? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1992.

Dr Gerard Hall, Head, School of Theology, McAuley Campus, ACU National, 30th October, 2002