Introduction

The concept of work-life balance, also referred to as ‘work-life conflict’ or ‘work-family conflict’, has received a great deal of attention from scholars in recent times. Whilst there have been various interpretations of the term, here we use the definition from the New Zealand Department of Labour website (2007) that describes it as “…effectively managing the juggling act between paid work and the other activities that are important to people”. Work-life imbalance can appear in various forms from the inability to remove oneself psychologically from the demands of the job (Messersmith, 2007:430), to a blurring of the lines between work and home life (Boswell and Olson-Buchanan, 2007:593).

Despite being a relatively new body of thought, the existence of academic studies on work-life balance is broad. Focuses range from political action (see Bryson, Warner-Smith, Brown and Fray, 2007) to the impact of technologies (see Boswell et. al. 2007) to its effect on worker’s attitudes (see McPherson, 2007). This saturation is hardly surprising given that, according to a report written on behalf of global research organisation ESOMAR, over two thirds of people across 23 different countries believe they lack work-life balance and nearly half felt personally affected by the imbalance (Echegaray, Cornish, and Donnelly, 2006:9).

Literature Review

Guest (2002:256), who provides a general review of the topic, believes that the contemporary prevalence of work-life imbalance is caused by the excessive demands of work in affluent societies. Factors such as technological advancements, the increasing need for higher efficiency levels and the entrance of women into the workforce (Guest, 2002:257) all contribute to the intensity of pressure on workers and cause inter-role conflict between the work and non-work spheres.

Publications discussing findings from The Australian Survey of Social Attitudes 2003 (Wilson, Meagher, Gibson, Denemark & Western, 2005 and van Wanrooy & Wilson, 2006) are useful for placing matters of work-life balance into an Australian context. Van Wanrooy et.al. (2006:349) found that those who work longer hours, despite reporting a higher work-family conflict, believe that long working hours are a choice. The authors claim that this perception is the result of the ‘liberal’ working time regime that exists in Australia (van Wanrooy et. al. 2006:350) wherein unreasonable demands on workers are structurally ingrained in culture. Subsequently, the gap between hours that workers would prefer and those they actually commit to is simply accepted due to the institutionalisation of standards and absence of solid legislation to regulate long working hours in the Australian workforce.

The results of The Australian Survey of Social Attitudes 2003 also show that the work-life balancing act impacts in greater (albeit slightly) levels on Australian families (Wilson et. al. 2005:55). Edgar (2005:3) notes the guilt experienced by parents who perhaps don’t spend as much time as they ‘ought’ to with their children due to work commitments. This is captured in the reflective piece by Stevens (2007), an artist who yearns for a healthier work-life balance. She writes:

My days were too full of distractions and interruptions. When I drew, I felt guilty about being away from my family. When I was with my family, I felt guilty about not drawing.

Whilst this example is useful in contextualising the damage work-life imbalance can cause Australian families, we now shift the focus to why this increasing trend is having a bearing on the attitudes and behaviours of workers; of immense relevance to organisations (Siegel, Post, Brockner, Fishman and Garden, 2005:13).

Drawing on an article in The Age newspaper, Gettler (2007:14) explains how advancements in technology and the onset of globalisation have produced a “syndrome of 24/7 availability”. It is through the accessibility of devices such as laptops, BlackBerrys and PDAs that work has entered the private realm and enabled workers to carry out job responsibilities from anywhere in the world. According to Gettler (2007:14) organisations are increasingly realising the need to provide solutions to their employee’s conflict between life spent working and time devoted to the family and other personal commitments. ‘The Way Ahead Report’ published by Managing Work/Life Balance International (2007) documents results of an annual benchmarking survey into the status of the work-life balance programs of organisations throughout Australia. The report promotes the benefits of participation to employees and also creates a standard for organisations to strive for.

In fact there are academic articles available that have sought to measure the effects of employer initiatives designed to minimise work-life conflict. For example Premeaux and Adkins (2007:705) reported that family-friendly policies (FFPs) contribute minimally to workers’ feelings of inter-role conflict. It would be expected, however, that employee support programs would improve the worker’s relationship with the organisation. The findings of Premeaux et.al. (2007:722) support this assumption; however it is through the antecedents of managerial support and less consequences of using FFPs that the connection is made. Workers may believe accepting such personal benefits as maternity leave to be frowned upon and therefore detrimental to their career. Thus, managerial support combined with cultural encouragement of family-friendly programs contribute positively to both work-life balance and organisational commitment.

In a similar vein, the study by Siegel et. al. (2005:14) was based on the hypothesis that low levels of work-life conflict and high levels of procedural fairness result in employee outcome favourability - which interact to influence organisational commitment. The results found that higher levels of work-life conflict do not necessarily lead to a decreased organisational commitment and that procedural fairness is a mitigating factor (Siegel et. al. 2005:17). Messersmith’s (2007:431) article summarises the body of research on the work-life conflict experienced by IT professionals and finds that work-life conflict is negatively correlated to organisational commitment. Within the Australian construction industry a survey amongst females found that whilst career and work environment were important predictors of organisational commitment, family variables, such as number of dependent children, failed to relate (Lingard and Lin, 2004:415).

Adding a technological dynamic to the relationship between work-life balance and organisational commitment, Boswell et. al. (2007:592) discovered that those more likely to use communication devices after working hours recorded higher ambition and job involvement levels. Despite not finding a connection between communicative technology use and emotional organisational commitment, the use of these devices during non-work time correlated positively with employee work-life conflict (Boswell et.al. 2007:603).

It should be noted that organisational commitment is a dynamic that is changing as work is no longer necessarily a major source of one’s identity (Bauman, 2005:27). Guest (2002:257-258) investigates the intentions of the new generation of workers, who supposedly place greater importance on achieving a work-life balance than previous generations. He reasons that these workers are less willing to display commitment to the organisation due to the unstable employment market and trend towards high employee turnover (Guest, 2002:257). The Meaning of Work Team (1987) used the question “would you still work if you won enough money never to need to work again?” to gauge the extent to which work is a central life interest. While most would perceive their motivation to work as stemming from the need to generate income it is possible that when faced with the decision to give up work this consciousness may be challenged.

Research Aims

This research aims to build on the theoretical framework provided by Meyer and Allen (1991) on organisational commitment and to fill the gaps in existing research on subjective measures of work-life balance. The main objective, therefore, is to investigate the relationship between Australian workers’ commitment to the organisation they work for and their perceptions of work-life balance.

Hypothesis 1: Workers with a higher perceived work-life balance will have a higher affective commitment to their paid work.

Hypothesis 2: There will be no significant relationship between work-life balance perceptions and continuance commitment.Hypothesis

Hypothesis 3: There will be no significant relationship between work-life balance perceptions and normative commitment.

Methodology

Procedure

Participants were selected based on a non-probability convenience sampling method, specifically, that is, the respondents were acquaintances of the researcher. This was due to the inability to access a database from which to obtain a large number of anonymous respondent details. The limitations of this sampling method are that it is not representative of the broader population, does not observe objectivity or validity and is more suitable to a qualitative methodology (Sarantakos, 2005:164). The advantages, however, are that it is quick, convenient and could be conducted within the budget. While not ideal, based on these considerations this method was considered to be most appropriate for the study at hand.

Fieldwork was conducted from the 21st of September, 2007 until the target sample of 30 responses was achieved on the 4th of October, 2007. Workers were phoned and invited to participate in the study, with involvement completely voluntary. Questionnaires were then mailed to each potential respondent which they were requested to return in the pre-addressed envelope provided. A response rate of 67% was achieved.

This method of data collection was selected because it was more time productive than face-to-face or telephone surveying and to ensure participant anonymity regardless of their connection to the researcher. However, Abrahamson (1983:327) points out the limitations of mailed questionnaires can include a low response rate and the self-contained element which eliminates the ability to answer any questions the respondent may have. To overcome these possible limitations, the questionnaire was designed with simple instructions and follow up telephone calls were made.

An explanatory statement was provided for each respondent introducing the researcher and the university, communicating the broad objectives of the study and outlining what was required as recommended by Bouma (2003:192). Ethical issues such as the right to refuse participation and provision of a phone number to call should the participant feel uncomfortable in any way were observed on for the data-collection instrument to ensure that questions were unambiguous and the intended message was received. Two members of the target sample were invited to participate in the pre-test and their feedback was welcomed.

Participants

Participants were 30 Australian citizens who undertook at least 30 hours of paid work per week and were not self-employed. It was decided that part-time or casual employees would have unusually low commitment levels or be indifferent towards their organisation and the self-employed would have abnormally high levels of organisational commitment and therefore were not suitable candidates for the dedicated sample. People who did not fulfil these characteristics were screened out in Section A of the questionnaire (and directed to Section Z – see Appendix A) and were not included in the final sample.

Had a full-scale version of this study been undertaken, quotas would be applied so that the profile demographics more closely reflect those of the actual Australian workforce population. However for the pilot study, the majority (67%, n=20) were female, with 55% (n=12) aged between 18 and 24 years, 41% (n=12) between 25 and 34 years and 3% (n=1) over 35 years. 59% (n=17) lived in Victoria and the remainder (n=12) reside in NSW. The occupations of respondents varied, with the highest proportions working in Technical/Healthcare (17%, n=5), Sales/Retail (14%, n=4) and Management/Business/Financial/Legal (10%, n=3) industries. Only one respondent had a dependent child.

Measures

Employee organisational commitment

Employee organisational commitment was measured using three types of organisational commitment; affective, continuance and normative (Meyer et. al. 1991). Affective commitment reflects a desire to maintain commitment to the organisation, generally accompanied by an emotional bond. Continuance commitment consists of an employees need to stay part of the organisation for fear of the consequences that may result from termination of employment. Lastly, normative commitment occurs when a worker continues to remain with the organisation because he or she feels obliged to do so for some reason or another.

To operationalise these concepts, participants were asked to respond to statements about how emotionally attached they were to their organisation, whether they continue to work for the organisation for fear of losing out financially or socially and how obliged they feel to continue with the organisation. This was gauged by a 10-point Leichhardt scale, with 1 representing ‘strongly disagree’ and 10 ‘strongly agree’. Responses were presented as mean values, with a higher mean representing higher agreement with the statement. The question “would you still work if you won enough money never to need to work again?” (The Meaning of Work Team 1987) referred to in the literature review of this report was included to gauge motivations for working.

Indications of behavioural (rather than psychological) commitment were measured by questions as to how long respondents hoped to stay working with the organisation for, their tendency towards positive or negative word of mouth, the amount of unpaid/overtime work undertaken or would reasonably be undertaken and discretionary effort exerted. These indicators may represent behavioural rather than psychological organisational commitment. Additionally, we were interested in how workers perceive work-life balance and organisational commitment, rather than the objective outcomes (such as absenteeism and reduced performance) these perceptions produce.

Work-life balance

As previously stated, for the purposes of this study work-life balance is defined as “…effectively managing the juggling act between paid work and the other activities that are important to people” (New Zealand Department of Labour website, 2007). The main question used to indicate work-life balance perceptions involved respondents rating their agreement with the statement “I feel that I have the right balance between work and life outside of work” on a 10-point scale, with 10 showing the most agreement and 1 the least. This question was designed to be consistent with the numerical scales for organisational commitment so that Pearson correlation analysis was possible and the hypotheses could be confirmed or denied.

Other questions used to measure work-life balance perceptions included occurrence-type questions, i.e. “How often do events at work affect your personal life?” and “How often would you say you sacrifice commitments in one sphere (work/personal) in order to fulfil demands of the other sphere?” Occurrence was measured as either never, or on a daily, weekly, monthly, yearly basis. Respondents were also asked which sphere normally prevails when a sacrifice is required; work, personal or it’s about even.

Other Variables

In previous research by White, Hill, McGovern, Mills and Smeaton (2003), level of autonomy and flexibility from the employer was shown to improve employee work-life balance. Therefore, these variables (in addition to the provision of FFPs) have been included in questioning as other possible influences of work-life balance or organisational commitment. Job satisfaction was also proposed as a potential correlate to organisational commitment, as found by Chen (2007:77) in the international tourist hotel industry.

It is also possible that the duration a person has been working for a certain organisation could contribute to work-life balance, as often people must work long hours to establish themselves within an organisation. In light of this, the question; “For how long have you been working for this organisation?” was included.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using software package SPSS. The data preparation stage consisted mostly of pre-coding and was followed by (as recommended by Sarantakos, 2005:366-367) definition of the variables in SPSS and then entry of the data. Due to the lack of control over response completeness of a mail-out survey, some responses came back as missing. These were excluded from the results in the preparation process and therefore total responses will not always equal 30.

Primary analysis consisted of running frequency tables which were used to check for errors in data entry or pre-coding and to assess initial results. The next level of analysis consisted of bi-variate calculations to identify relationships between variables. Significance testing was utilised to identify statistically significant relationships between nominated variables. Pearson correlation methodology statistics were used to locate the nature and strength of the linear relationships between the independent variable and the scale questions. Graphs were constructed to illustrate graphically the relations between some variables.

Please note that due to the small sample size (n=30); results are indicative at best and certainly not reflective of the broader population.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The overall mean score for the main work-life balance measure is high (m= 7.30, on a ten point scale where 1 indicates a low level of satisfaction with worklife balance and 10 a high level of satisfaction). However, the standard deviation (2.34) is also high which indicates a considerable range of satisfaction within the sample (see table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Summary statistics for variables

Summary statistics for variables |

| Variable (n=30) |

Range |

Mean |

SD |

| Flexible working hours or family friendly policies |

1-10 |

7.63 |

2.25 |

| Perception of work-life balance |

1-10 |

7.30 |

2.34 |

| Degree of autonomy |

1-10 |

7.27 |

1.98 |

| Identification with goals of organisation |

1-10 |

7.10 |

2.22 |

| Emotional attachment |

1-10 |

5.77 |

2.40 |

| Difficulty of finding an attractive alternative |

1-10 |

5.37 |

2.74 |

| Perceived financial consequences |

1-10 |

4.00 |

2.69 |

| Perceived obligation to organisation |

1-10 |

3.60 |

2.84 |

| Perceived social consequences |

1-10 |

2.83 |

1.88 |

The results also suggest a high prevalence of flexible working hours or FFPs and degree of autonomy among the sample (means of 7.63 and 7.27 respectively) although it must be taken into account that there are a considerable range of responses as indicated by the standard deviations.

The most variance in answers was shown in perceived obligation to the organisation (with a standard deviation of 2.84) and the least in the perceived social consequences, with a standard deviation of 1.88 and the lowest mean for overall indicators (2.83).

All descriptive statistics are provided in Appendix B.

Correlates to work-life balance

Three variables showed significant correlations to perceived work-life balance; all positively related. They included identification with the goals of the organisation, emotional attachment and the availability of flexible working hours or FFPs (see table 1.2).

Table 1.2: Correlations of variables to perceived work-life balance

Correlation to perceived work-life balance |

| Variable (n=30) |

Pearson Correlation |

Sig. (1-tailed) |

| Identification with goals of organisation |

0.533 |

0.001* |

| Emotional attachment |

0.461 |

0.005* |

| Flexible working hours or family friendly policies |

0.343 |

0.032* |

| Degree of autonomy |

0.220 |

0.121 |

| Perceived obligation to organisation |

-0.189 |

0.158 |

| Perceived financial consequences |

-0.115 |

0.272 |

| Perceived social consequences |

0.028 |

0.443 |

*significant at p<0.05

Hypothesis 1, that workers with a higher perceived work-life balance will have a higher affective commitment to their paid work was confirmed; emotional attachment is shown to positively correlate with perceived work-life balance. This aligns with the work of Messersmith (2007:431), who reports that work-life conflict is negatively correlated to organisational commitment. Hypothesis 2, that there will be no significant relationship between work-life balance perceptions and continuance commitment has also been confirmed with perceived financial and social consequences showing no significant relationship to work-life balance. Hypothesis 3, that there will be no significant relationship between work-life balance perceptions and normative commitment has been affirmed with perceived obligation showing no significant relationship to work-life balance.

An unanticipated finding was that of employee identification with the goals of the organisation showing the strongest correlation to work-life balance. This relationship merits further research starting with a literature search followed by some qualitative approaches (for example ethnography) to uncover the dynamics of this relationship.

That the allowance of flexible working arrangements and availability of FFPs positively correlates to work-life balance does not support findings in Premeaux et.al. (2007:705) who reported that FFPs exert minimal effects on work-life conflict. The finding can also be related to Siegel et. al. (2005:13) who found that procedural fairness has a moderating influence in the relationship between organisational commitment and work-life balance.

Multiple regression analysis for these variables was attempted, however returned an R-squared of 0.25 (the degree to which the independent variables could explain the dependent variable) which is too low, and not statistically robust (see Appendix 3).

Demographic bi-variate analysis

Cross-tabulation analysis for demographics is limited due to the uneven spread within each demographic segment, therefore only the segments with sufficient numbers have been used.

The only significant difference recorded was in relation to perceived obligation to remain with the organisation (see table 2.1). Males (with a mean of 5.20) were significantly more inclined to feel obliged to stay than females (mean of 2.80). Perceived work-life balance was slightly higher for females than for males (means of 7.80 and 6.30 respectively). �Table 2.1: Mean statistics for demographics

| |

Age |

Gender |

State |

| Variable |

18-24 years (n=16) |

25-34 years (n=12) |

Male (n=10) |

Female (n=20) |

NSW (n=12) |

Vic (n=17) |

| Perceived work-life balance |

7.50 |

7.00 |

6.30 |

7.80 |

7.42 |

7.24 |

| Emotional attachment |

6.00 |

5.58 |

5.50 |

5.90 |

5.75 |

5.94 |

| Degree of autonomy |

6.75 |

8.17 |

6.40 |

7.70 |

7.75 |

7.06 |

| Identification with goals of organisation |

7.31 |

6.75 |

6.20 |

7.55 |

6.58 |

7.47 |

| Perceived financial consequences |

4.50 |

3.50 |

4.30 |

3.85 |

4.75 |

3.65 |

| Perceived social consequences |

3.06 |

2.50 |

2.50 |

3.00 |

2.83 |

2.71 |

| Flexible working hours or family friendly policies |

7.88 |

7.33 |

7.30 |

7.80 |

7.50 |

7.71 |

| Perceived obligation to organisation |

3.50 |

4.00 |

5.20* |

2.80* |

4.58 |

3.06 |

| Attraction of alternatives |

5.56 |

5.08 |

4.90 |

5.60* |

6.17 |

4.76 |

* significance level of 0.05 based on two-sided tests assuming equal variances

Overtime/unpaid job-related work analysis

Workers undertaking at least some overtime/unpaid job-related work per week were significantly more likely than those who do not to cite the work sphere as prevailing when a work-life conflict occurs (see table 3.1). Conversely, a significantly higher proportion of those who undertake no form of overtime believe it is their personal sphere that normally wins out.

Table 3.1: Overtime/unpaid job-related work per week by prevailing sphere - proportions

| |

Overtime/unpaid job-related work undertaken (per week) |

| Prevailing sphere |

None (n=10) |

At least some (n=19) |

| Work sphere |

10%* |

58%* |

| Personal sphere |

40%* |

5%* |

| It’s about even |

50%* |

37% |

| Total |

100% |

100% |

* significance level of 0.05 based on two-sided tests

‘Don’t know’ value removed from column variables

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding

These results concur with those of van Wanrooy et. al. (2006:349) who found that people who work longer hours were more likely to encounter work-life conflict. The fact that in this study, 58% of those who partake in at least some overtime or unpaid job-related work per week said that work sphere will prevail when a sacrifice is required indicates a more negative outcome (and therefore greater conflict) than those who do not.

When gauging whether long working hours are the result of choice - as found by Wanrooy et. al. (2006:349) - it is interesting to note that 77% (n=23) of the sample were prepared to participate in at least some overtime or unpaid job-related work each week. Table 3.2 indicates that affective commitment is significantly higher among those who believed partaking in at least some overtime per week was reasonable than those who don’t believe any overtime is acceptable (means of 6.48 and 3.17 respectively).

�Table 3.2: Overtime/unpaid job-related work prepared to undertake per week by emotional attachment - mean values

| |

Overtime/unpaid job-related work comfortable with undertaking (per week) |

| |

None |

At least some |

| n= |

6 |

23 |

| Emotional attachment to the organisation |

3.17* |

6.48* |

* significance level of 0.05 based on two-sided tests assuming equal variances

percentages may not total 100 due to rounding

Motivations for working

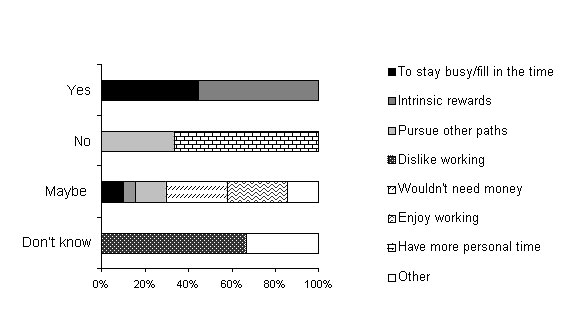

When asked hypothetically, would they continue to work if they won enough money to never work again, 54% (n=14) reported ‘yes’, 8% (n=2) ‘no’, 35% (n=9) ‘maybe’ and 4% (n=1) said ‘don’t know’. For the reasons given, see figure 4.1. Those who reported they would keep working commonly cited the feeling of boredom that would result if they gave up their job. Pre-coded responses illustrating this point included; “I think I’d find myself very bored and would not be able to maintain the lifestyle I would have achieved” and “I would get bored if I didn’t work”. No one reported the reason as being because of their commitment to the organisation.

Figure 4.1: Intention to continue working if enough money was won that meant never having to work again by reason for decision

Discussion

With mean scores above 7 for the availability of flexible working hours or family friendly policies, perception of work-life balance, degree of autonomy and identification with the goals of the organisation (provided they know what these are) the sample appears to be in control of their working lives. This finding somewhat contradicts those of Echegaray et. al. (2006:9) who found that workers were adversely affected by work-life balance issues.

The most significant correlation to work-life balance - employee alignment with the goals of the organisation - is a useful point to start in attempting to improve organisational commitment. Messersmith (2007:443) suggests encouraging workers to “align personal goals with career-related goals and to include family members in career-related goal striving.” Whilst this study didn’t approach the subject of family influence, the findings imply that consistent values are what drive a healthy work-life balance. Does this mean that organisations with more clearly stated goals have higher employee commitment levels? This would certainly merit further investigation. Given the younger skew in this sample, we could conclude that younger people are either aligning their personal goals with the organisation they work for or they are choosing their workplace based on its implicit values.

Whilst it is apparent from the findings that - given the low overall mean score for concern with losing social ties – emotional attachment does not consist of the desire to maintain friendships, emotional attachment could have a connection to identification with organisational goals. Another issue is that of the provision of flexible working arrangements on work-life balance. Has the increased prevalence of this practice meant that workers now simply expect it? In which case, varying levels of expectations of workers could be assessed, along with a longitudinal study comparing this to previous generations.

This study was unable to confirm the studies of Boswell et. al. (2007) as it did not approach the use of communicative technologies outside working hours. It is also limited in its ability to provide insights on the affects of the ‘second shift’, especially in the case of female workers, as pressures of personal commitments were not explored.

Limitations

A significant limitation of this study is the age of the sample; 96% were aged under 35 years. A study using this demographic would better suit a study into the changing attitudes of younger workers and implications for the future of the Australian workforce. Furthermore, there was no representation from any states other than Victoria and NSW and was extremely limited in representing households with children.

Analysis was conducted at a basic level. More complex analysis should be used in future studies to determine causal relationships between variables.

An issue that this study fails to address is the relationship between expectations of what work should entail and people’s concepts of work-life balance. For instance, Hewlett and Luce’s (2006:51) research on ‘extreme jobs’ (defined as working 60 or more hours per week, involving unpredictable flows of work, tight deadlines and high responsibility), finds that these types of jobs are not a rarity and occur in a wide range of industries. Despite these seemingly unreasonable work expectations, 66% of those surveyed reported that they loved their jobs and 64% believed the workload is self-inflicted (Hewlett et. al. 2006:51-52). This shows that the relationship between hours worked and perception of work-life balance is not necessarily straightforward.

It can be safely assumed that a worker’s satisfaction with their job is judged by what they expect it to deliver. If a worker’s intentions are to work their way up the corporate ladder they may be happy to work overtime. However, if they are simply working to put themselves through university an increase in hours worked may sabotage study time. A question could have been included in this study to gauge the importance of work-life balance to each individual and what actually constitutes work life balance to them. No doubt there will be research into this area in the future. |